Manga’s Origins

Japan has a long history of pictorial story telling – A famous early example dating from the 12th century, ‘Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga’ (Animal-people cartoons) consists of a series of scrolls. Up to 11 meters long, they depict wild birds and animals behaving in comical and human-like ways.

These scrolls were likely not designed to be viewed at once but rolled in a traditional right to left fashion by assistants – The rolling effect creating a moving narrative.

As a result, ‘Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga’ are debatably, but still often, referred to as the earliest example of manga.

At the time these types of scrolls would only have been available for viewing by the elite and top echelon of Japanese society, hardly what could be considered an accessible mass-market artform such as the manga we know of today.

A more modern and mass market example of the same artistic inclination can be seen in the uniquely Japanese street performance art, Kamishibai (paper play).

A popular form of entertainment in the pre-WW2 era – Kamishibai storytellers, called kamishibaiya would set up miniature portable stages on busy street corners and intersections. The stages were designed to hold artworks that would be exchanged as the performer verbally narrated a story.

Kamishibai all but disappeared in post war Japan with the introduction of television and early manga publications becoming inexpensive and widely available.

In modern day Tokyo, Kamishibaiya can occasionally be found performing in and around popular attractions and playgrounds. If you happen to see one it is worth stopping by and dropping a tip for the performers keeping the unique artform alive.

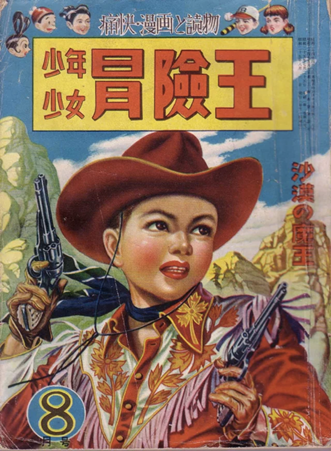

It was not until the mid 20th Century, post WW2 period that what we know of as modern manga came into existence. It was usually split into 2 distinct categories – ‘boy’ (Shonen) and girl (Shojyo) – and aimed primarily at children and teenagers.

Today an example of this style can be seen in the immensely popular Shonen Jump Magazine.

(Examples of early Shyoujyo / Girl) and Shyonen / Boy magazines.)

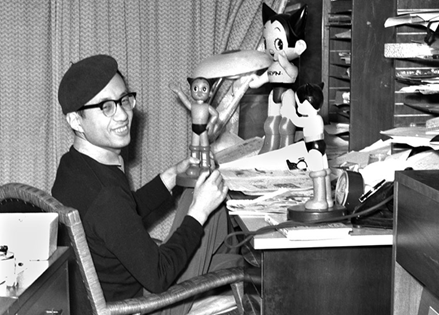

During this time the specific aesthetic style associated with manga was also developed – Heavily influenced by a Western, particularly Disney style. Typified by the work of ‘The Godfather of Manga’ Osamu Tezuka; known for his works ‘Astro Boy’ and ‘Kimba the White Lion’.

The influence of Disney’s Mickey Mouse can for example, be seen in Tezuka’s character design of Astro boy.

The Birth of Gekiga (‘Dramatic Pictures’.)

The word gekiga translates to ‘dramatic pictures’.

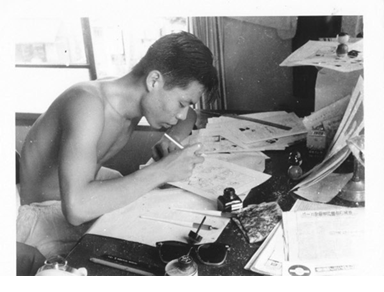

The term was coined, the style consciously developed and a manifesto was drafted in the late 1950’s by a group of artists led by Yoshihiro Tatsumi.

Conceived as a counterpoint to the widespread children’s manga style, Gekiga was aimed explicitly at adults.

Utilising dark, violent, sexual themes and imagery. It was heavily influenced in style and layout by contemporary Japanese cinema; such as the enormously popular and critically acclaimed ‘Seven Samurai’ by director Akira Kurosawa.

Gekiga fairly quickly found a large and enthusiastic audience among teenagers and adults that grew up on children’s manga.

By the 1960’s Gekiga titles were being embraced by big publishing houses and movie adaptations of popular titles started to appear. Such as a series of successful movie adaptations of the popular 1970s Gekiga Manga ‘Lone Wolf and Cub’. Including a western release, re-cut and renamed ‘Shogun Assassin’, which herald that Gekiga had hit the mainstream.

Today, as the depth and breadth of manga styles has exponentially grown Gekiga is so popular that it is no longer considered alternative or underground in either the East or West.

Garo and The Rise of Alternative Manga

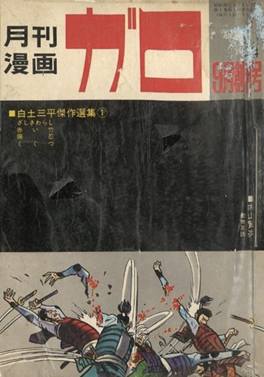

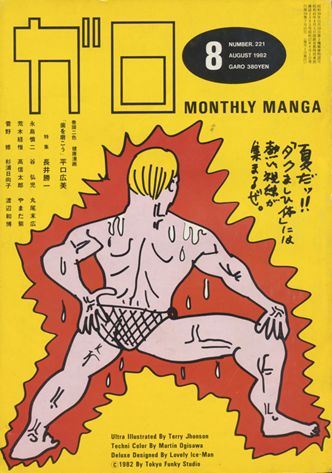

No history of alternative manga would be complete without mention of the celebrated Garo magazine.

A specifically alternative manga magazine that launched in 1964 to offer an outlet for artists to explore more experimental and subversive forms, styles and themes. At the height of its popularity the magazine had a circulation of 50 to 80,000 per month.

The impact and influence of Garo today cannot be understated – Indeed, most of the manga movements of the following decades were born between its covers.

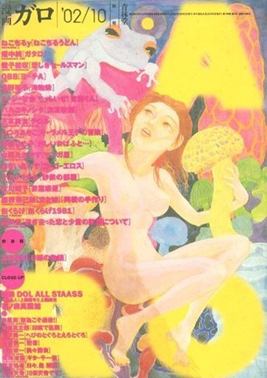

(Garo Magazine covers: First Issue from 1964 + the 2002 Final Issue.)

The first prominent artistic voice to rise from the pages of Garo was Yoshiharu Tsuge.

Having already published with the magazine for several years, Tsuge felt encouraged by the editors to explore a more experimental style and pursue his singular artistic vision – Leading to Tsuge braking through with his 1968 manga ‘Screw Style’ (Nejishiki).

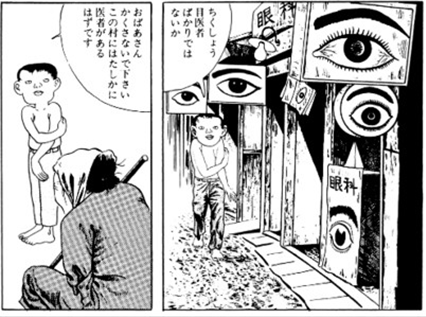

‘Screw Style’ is a dark surrealist short based on the authors dream -The protagonist, assumed to be Tsuge himself, is bit by a jelly fish on an unfamiliar beach and proceeds to search for a doctor in a nearby village.

Variously, the village contains: Dozens of eye-doctors; the protagonists’ own mother and eventually, a gynaecologist who installs a screw-tap in the protagonists’ damaged vein while having sex with him.

‘Screw style’ popularised the first significant movement within alternative manga. A deeply personal, autobiographical (often read as confessional) style now known as ‘Watakushi Manga’ – Simply translated as ‘About me’ manga, the style was somewhat of a revelation for the artform that had previously been dominated by narrative driven, historical and action genres.

(An English translation of ‘Screw Style’ can be readily found online from several sources.)

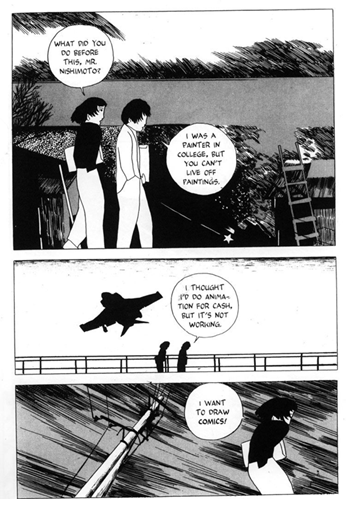

Another significant Watakushi artist Shin’ichi Abe created short manga published in Garo and other magazines in the early and mid 1970s. Utilising the author-as-protagonist style associated with Watakushi, Abe wrote about his own struggles with romance, art, alcohol addiction, and mental illness.

A collection of Abe’s work can be found translated into English in ‘That Miyoko Asagaya Feeling’ published by Black Hook Press. Hopefully still available for purchase at the time of reading.

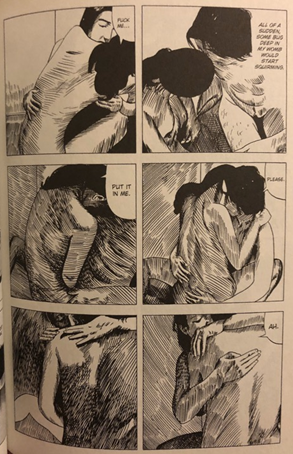

A third example – Seiichi Hayashi created a serialized story that was published in Garo between 1970 and 1971 and later collected as Red Colored Elegy (Sekishoku Erejii). The story focuses on the turbulent romantic relationship of two young artists living together and attempting to navigate life in 1970s Tokyo. A domestic arrangement that was unusual and taboo at the time.

Interestingly, despite the work being distinctly Watakushi in style, Hayashi later disclosed that the manga was a work of fiction and that he was surprised that people assumed it was autobiographical.

Even today reading these old Watakushi manga can feel vaguely voyeuristic, like peeking through a window into lives, and parts of the human psyche that should be hidden.

It’s not hard to imagine how radical this would have been in the conservative and homogenous culture of 1960s and 1970s Japan.

Heta Uma – Bad but Good

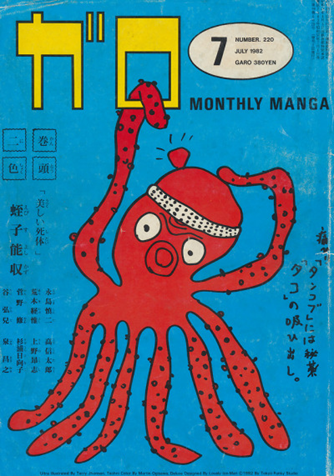

The 1980’s saw the rise of an aesthetic style known as Heta Uma.

The term has a particularly Japanese sensibility and is not simple to translate. Often it is simply termed ‘Bad but good’ in English – which is a fine translation – but a more precise understanding would be ‘crude but charming’ or ‘poorly made but captivating’.

Heta Uma is a quintessentially Japanese Lowbrow art form. Its highest philosophical aspirations are conveying the concepts that anyone can create art, and it can be fun. It was initially closely associated with the 1980’s punk rock and DIY movements, and as a result Heta Uma manga is typified by a deliberately amateurish and childish sensibility. They are typically surreal, violent, playful and humorous all at once.

Indeed, many Heta Uma manga read like a 1980s big budget action or horror film – Filtered through the sensibilities of a thirteen year old and rendered by 8 Year old.

The result landing somewhere between a Troma film and Beavis and Butthead.

Heta Uma’s global influence can be glimpsed in the amateur webcomic movement and shows such as South Park – the early seasons in particular.

(Early 1980s Garo covers displaying the Heta-Uma style.)

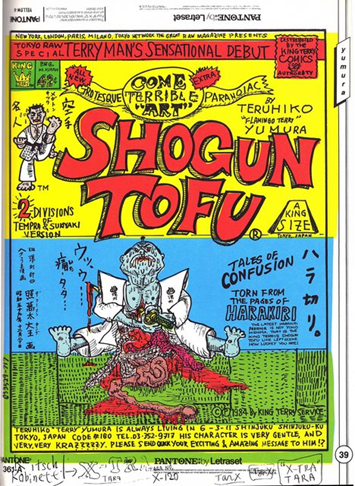

Interestingly Teruhiko Yumura aka King Terry, considered to be the godfather of the Heta Uma style, was in fact a trained illustrator.

His work was exposed to an international audience through publication in Art Spiegelman’s renowned American comic anthology magazine ‘Raw’.

(Pages from Shogun Tofu by Teruhiko Yumura aka Terry Yumura aka King Terry – Published in English in a 1984 edition of RAW.)

Ero-Guro Nansensu – Dark soft erotica

Ero Guro Nansensu, often shortened to just Ero Guro, is a term that uses a common Japanese phenomenon known as Wasei Eigo, whereby English words, or parts of English words, are combined to create new words that don’t exist in English or Japanese. In this case Ero Guro Nansensu is a portmanteau of the English words erotic, grotesque and nonsense.

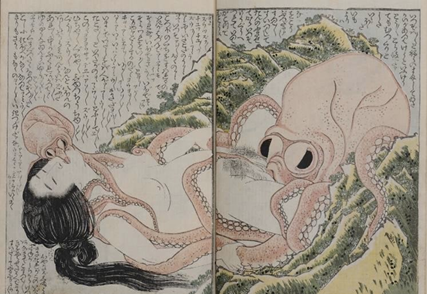

The term itself originates in the rebellious ‘moga and mobo’ (modern girl and modern boy) youth culture of 1920’s Tokyo. However, the style could be traced as far back as the early 1800s. A prominent example being the infamous 1814 work, ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ by Katsushika Hokusai – Often cited as the first artistic representation of ‘tentacle porn’.

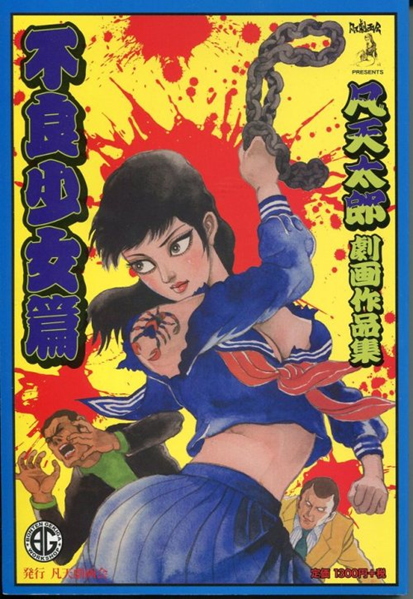

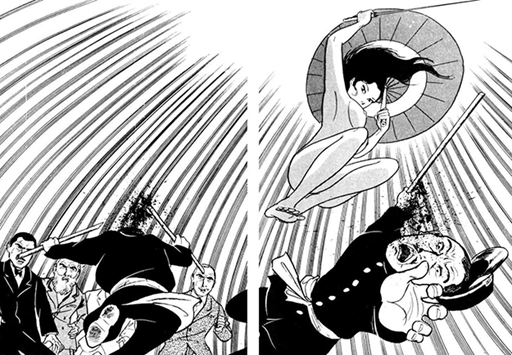

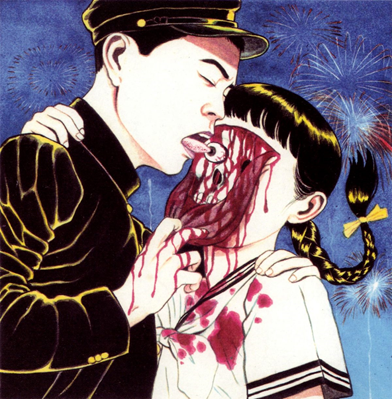

The 1980s to 1990s saw the development of a manga style combining Shojyo (young girl) manga aesthetics – typified by soft or muted light and colour pallets; with themes of romance bordering on soft erotica (think Sailor Moon) – and the often graphic horror imagery of these earlier works.

Modern Ero Guro artists subvert the conventions of the Shojyo genre by exploring the dark subtext inherent in the ostensibly innocent style, teasing it out and placing it un-ambiguously on the page to confront the reader. Creating an uncomfortable and potent merging of familiar nostalgia and anxious fear; with a heavily sexual overtone.

Something akin to the works of Western artists such as David Lynch, David Cronenberg and HR Geiger.

One of the most notable creators and artists of the early era manga Ero Guro style is Suehiro Maruo.

Suehiro was a staple presence in the aforementioned Garo and published several one-shot manga as well. Sadly, his work has rarely been translated in English – and what has been is often extremely rare and consequently expensive.

One of Suehiro’s better known manga, ‘Shojyo Tsubaki’ (Camillea Flower Girl), released in English as ‘Mr Arashi’s Amazing Freakshow;’ is about an orphaned girl taken in by a travelling circus, and was later adapted into a feature length anime in 1992.

A film that was immediately and unceremoniously banned for distribution everywhere, including Japan upon release, due its depictions of abuse and extreme gore.

Various edited version of the film have been released over the subsequent years (confusingly released in English as ‘Midori’), however there is still debate about whether the full uncut version has been seen by anyone, or even exists anymore.

He is most well-known to international audiences for his illustration work on band posters and album covers – Most notably John Zorn’s Naked City LP releases.

The Death of Garo

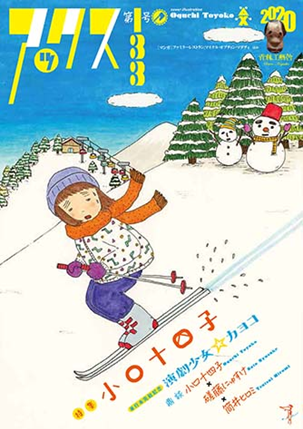

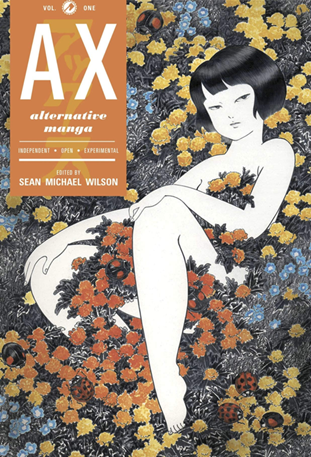

The rise of the internet as a means for independent publishing, a major economic downturn in Japan, and the death of founding editor Katsuichi Nagai saw Garo collapse in the late 1990’s.

Several editorial staff from Garo went on to found alternative manga magazine AX, which is still running today, although it has never achieved the same success as Garo did at the height of its popularity.

(A 2020 edition of AX + the English language anthology of AX highlights from 2010.)

Contemporary Alternative Manga

Heta-uma and Ero-Guro remain relatively popular styles and new titles regularly appear among the approximately two billion manga sold every year in Japan.

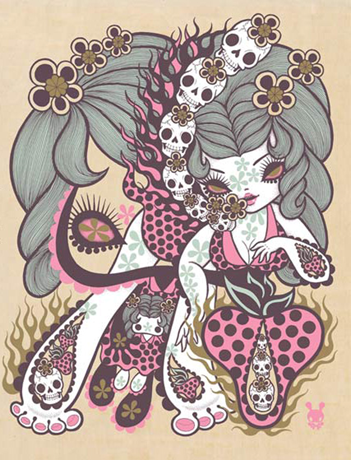

A modern offshoot of Ero-guro that emerged in the late 1990’s early 2000’s is dubbed ‘Abuna-Kawaii’ (Cute but Dangerous).

This iteration drew on a combination of horror and the super cute aesthetic encapsulated by Sanrio and their Hello Kitty character.

The most well-known proponent of this style is Junko Mizuno,who has achieved fame in Japan and exposure in the West due to illustrating album covers and posters for bands such as Faith No More, Melvins and Mudhoney.

Junko has also ventured into the designer toy scene – Collaborating with popular toy brands such as Kidrobot, as well as regularly producing her own self released pieces.

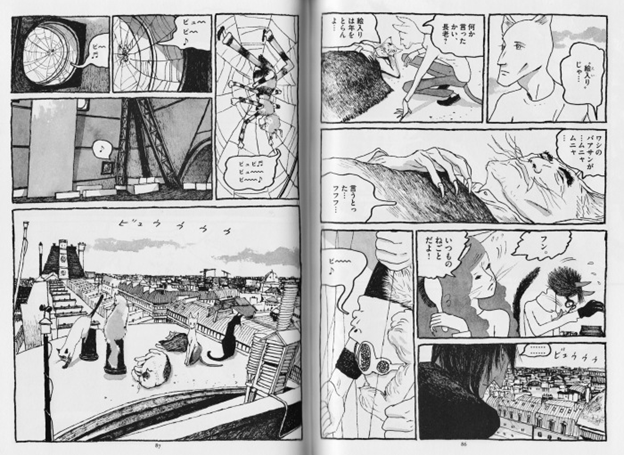

Interestingly – Some alternative manga artists today, such as the brilliant Taiyo Matsumoto are now embracing European underground comic books and incorporating their aesthetic into manga.

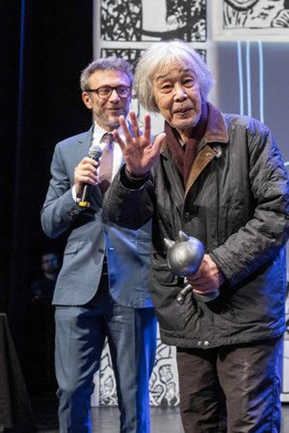

The English translation of Matsumoto’s ‘Rūvuru no Neko’ (Cats of the Lourve) even won an Eisner award (one of the highest awards in the English Language comics scene) in 2020, completing the cycle.

The Future of Alternative Manga

Due to its nature as an outsider art form and the lack of a popular central publishing platform like Garo, it is difficult to find alternative and underground manga today in 2021 – even in Japan. However, the self-publishing, internet and zine scenes – though small – remain strong and vibrant.

If you happen to be in Tokyo at some point in the future, take a few hours to visit the legendary Nakano Broadway mall, squished in among the hundreds of other micro shops you will find the fabled independent bookstore Taco Che.

For a first-hand experience of the contemporary underground scene, you can’t do better.

To this day, very little underground manga is translated into English as most Western publishers are still focused on the early Gekiga and Watakushi manga instead – much of which still remains unpublished in English.

That said, there are several small-run indie publishers doing amazing work – Such as the aforementioned Black Hook Press and Retrofit Comics. As well as more established publishers such as Drawn and Quarterly and Breakdown Press who regularly print translated editions of alternate and underground manga.

Due to the lag between Japanese publication and English translation it can be decades before works are available. Supporting small and independent publishers will help these remarkable works be produced in English – Otherwise you could always learn Japanese to get your manga kick!

Links

A list of English language, alternate and underground manga publishers follow for your convenience:

- Black Hook Press – Website

- Breakdown Press – Website

- Verite Magazine – Website

- Drawn and Quarterly – Website

- Glacier Bay Books – Website

- Hollow Press – Website

- Komikss – Website

- RetRoFit – Website

Article header art by Dan Thrax.