It was a strange time the late 1980s and early 1990s – When zines, thousands of weird little homemade documents – were sliding and slithering through the postal system. I had made a 4 by 5-inch frenetic tract called ‘This is Your Final Warning,’ and sent it to various addresses I found in Semiotext(e) U.S.A. and High Weirdness by Mail.

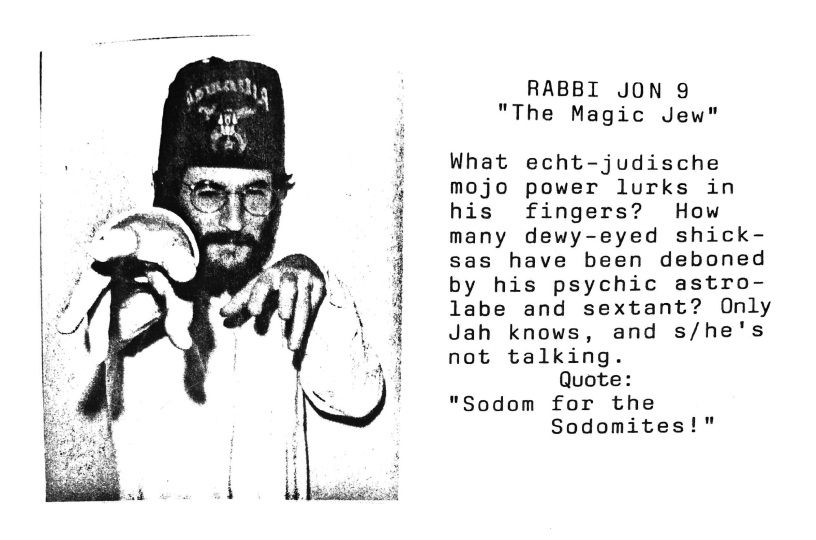

In reply came all sorts of bizarrerie, most notably The Moorish Science Monitor, from Verlag Golem in Providence RI. The masthead listed various implausible personages responsible for making this zine happen: Debbie Schwartz-Doppelganger, Pinchas Weisskopf, Jacob Rabinowitz, Ali Hossein Abu’l Jihad, Rabbi Jon-9, and Joe Bastard Armpit of the Miskatonic Police Force.

To this was appended a note saying that he/she/they wanted to reprint my ‘Final Warning.’

Beyond that was just this statement: “Silence equals consent.”

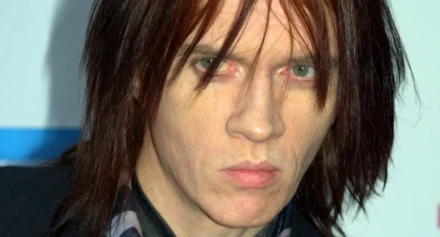

That was how I first came into contact with the person now known as Mildred Faintly (born 1958 in New Jersey, USA).

We began an exchange of letters, xeroxed screeds, collages, poetry, manifestos, and other bits of postal flotsam.

From Volume 5, Issue 3 of ‘The Moorish Science Monitor’.

At this time, Factsheet Five (FF) was the epicentre of the zine movement, reviewing hundreds of publications in every issue. To put faces with names, and to celebrate the outpouring of DIY wildness, FF founder Mike Gunderloy would organize parties for anyone who could come to his place outside Albany, New York.

This was only a four-hour drive for me, and I had a friend living in Albany, so I went to one of these parties with the intention of meeting the person and/or people who’d sent me so much wonderful weirdness.

Entering Gunderloy’s house – already packed with anarcho-punks, freaks, drunks, crypto-pervs, and a few geniuses and mystics – I asked if Verlag Golem was there.

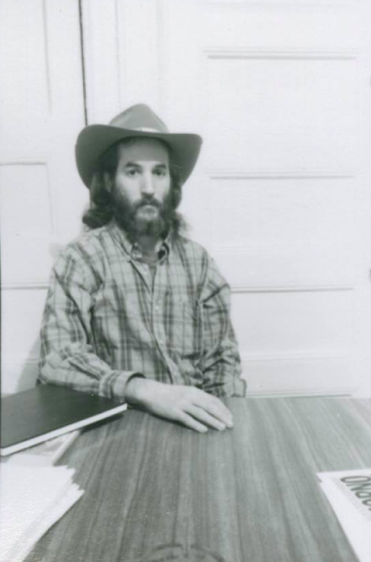

“Yeah. Jake’s here.” And I was pointed in the direction of the person then going by the name of Jacob Rabinowitz.

In the decades since, our friendship has continued to flourish.

I’d drive to New Jersey or Manhattan and we’d spend a few days helling around Chinatown, the Lower East Side, or the hillbilly hinterlands of the Catskills.

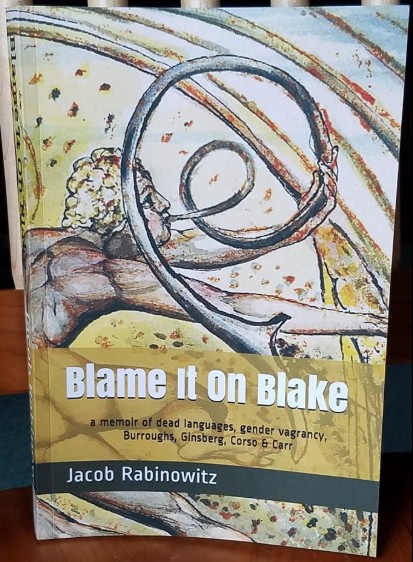

The Autonomedia publishing collective was one point of connection. Though neither of us fit neatly into the anarcho-doper milieu, they published two books for both of us.

Another link was our mutual friend and mentor Hakim Bey, who had resurrected The Moorish Orthodox Church and pulled us in with his wit and ensorcelling charm.

(Over the years, Mildred and I both edited a number of issues of The Moorish Science Monitor.)

On my visits, I heard stories of Mildred’s early days, using other names, as a young friend of Beat paragons Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso.

I’d tell stories of the Burnt-Over District, that region of New York State which bred much religious madness (top of the list: Mormonism and Spiritualism.)

When eventually given a copy of ‘This is Your Final Warning’, my collected literary Zigguratica, the author of Howl declared, “It appears to be gibberish” – A blurb I’ve never been able to use.

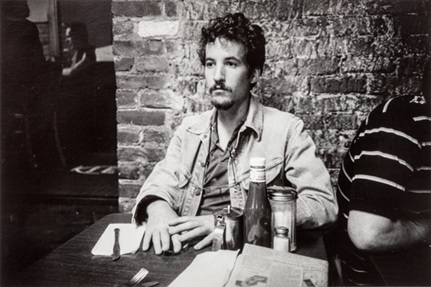

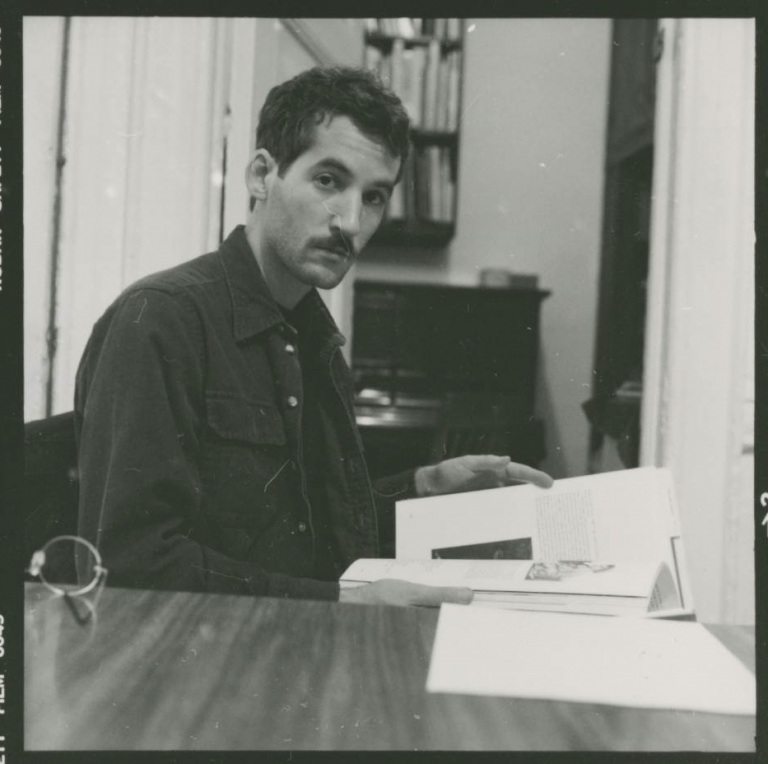

Specifically, clockwise from top left: 1987, 1984, and 1994.

I mainly stayed on my home turf, digging into lost and/or imaginal history. From forays to Ireland, Israel, and New England over the years came poems, letters, and translations from Mildred.

The letters were always amusing and astute.

The poems were often brilliant; the translations were unlike anything being done by the high priests of academic boredom. Out of Latin came the complete poetic works of Catullus; from Hebrew, ‘The Unholy Bible.’ Dante’s ‘Purgatorio’ and ‘Paradiso’, Chinese poetry from 1300 years ago, German feminist expressionism, Yiddish lesbian symbolist fantasmagoria, ‘Sappho for Girls’, ‘The Rotting Goddess’, early Christian archaeology, and hieroglyphics – This list doesn’t exhaust the bewildering brilliance of her translations, scholarship and writing in general.

Focusing now exclusively on translating and championing poetry by women, Mildred Faintly has built up a body of work that spans the globe and delves into depths few other writers would peer into. Let alone dare to enter by full and fearless immersion.

Read a condensed version of our recent conversation, conducted over video chat and email, below…

How many languages do you know?

About 17. But most of them are dead.

It’s much easier to study a language if it holds still.

Learning languages takes hard work and concentration—or did it come easy to you?

I assure you, every inch of my ability was hard won.

There are people who have an easy gift for languages – and I sort of hate them.

Why have you studied such a wide variety of languages – both ancient and modern – from around the globe?

I have roved through languages as I have roved through religions – inseparable quests for me.

Ancient languages were the key to scriptures that held ancient wisdom – I can’t say I’ve grown wise, but at least I’ve become ancient.

You describe yourself roving through languages, and you use the word “quest.”

Are you looking for something?

At the beginning I was just pursuing my tastes and hoping to make a reputation.

In the last few years I have turned my attention exclusively to poetry by women. I am attempting to build as it were, a Great Wall of Girls, so imposing in scope that women’s genius may be seen even from outer space.

I’m guessing this relates to your transition?

I am using translation to learn what it can mean to be a woman.

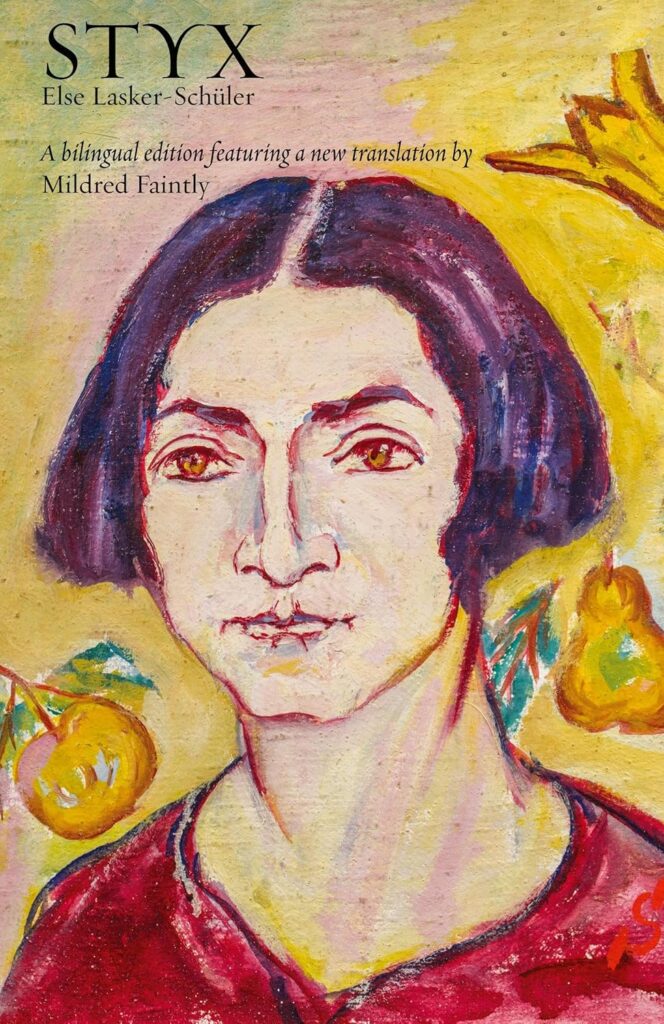

My primary source for this kind of insight is of course other women I know personally – but brilliant women like Sappho, Else Lasker-Schüler, and Marina Tsvetaeva impart an understanding of womanhood that is otherwise unattainable.

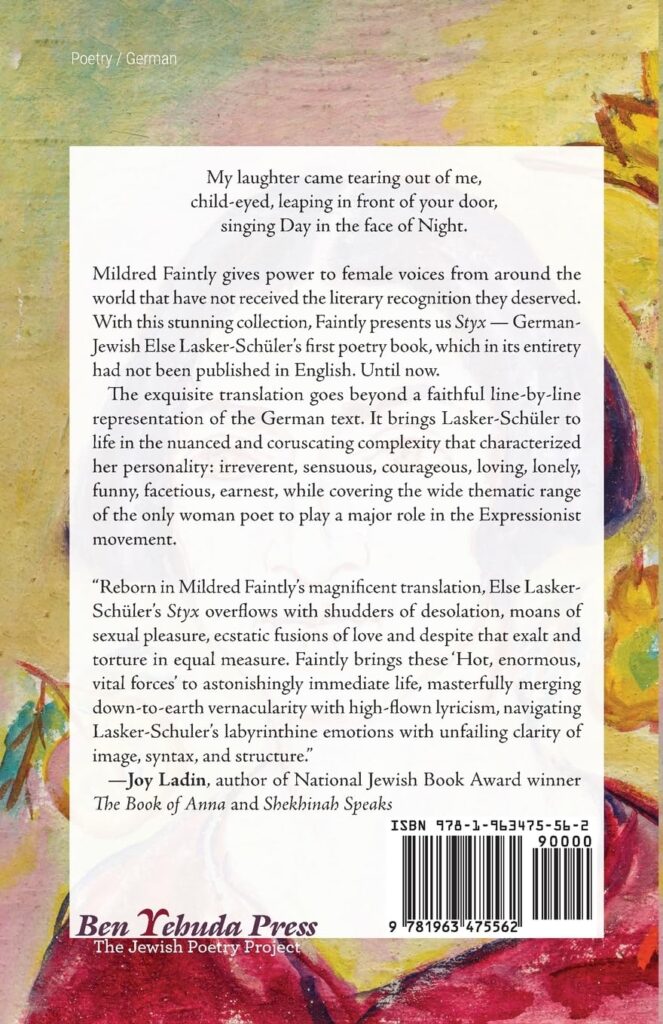

Published 2024 by Ben Yehuda Press.

Originally published 1901 in German.

Can you tell us about your transition?

It came about very slowly, almost in geological time.

There was a lot to figure out.

I am a woman from an earlier century – the twentieth. When I was in my twenties no one understood that anatomy was one thing, sexual preference another, and gender identification a third – and that these three aspects of personhood didn’t necessarily align in a symmetrical way.

Back then gays thought that crossdressers were giving homosexuality a bad name.

Tools for my self-understanding just weren’t available, so it took me a while to sort things out.

Did you identify as a crossdresser?

No, I just thought I was incredibly perverted.

I justified this to myself by imagining I was a decadent libertine – there was a lot of self-hatred in that mix.

The only images of trans people current in the mainstream then were crossdressers as psychotic murderers, like in ‘Psycho‘ and ‘Silence of the Lambs.’

“I dreamed I was a serial killer in my Maidenform bra.”

The only positive pictures of trans folk were in porn.

What changed your view of yourself?

I was pretty much out of the loop while society was evolving on these heads – bad luck for me career-wise.

I missed out on transition while it was still newsy.

The moment of truth came when my wife was being treated for cancer – It was successful, by the way, four years of clean scans now.

Anyhow, I was at a meeting of a cancer caregiver support group, and I was the only man there. Men don’t tend to be very good at showing up at times like those.

Husbands’ reactions often range from having an affair to wondering, “Does this mean dinner’s going to be late?”

As I listened to those women, whose experience was entirely mine, I realized I wasn’t the only man in the room.

There were no men in that room.

In caring for my wife some of my female qualities found their best expression.

I don’t mean to suggest that women’s roles should be limited to service and caregiving. I would, however, assert that for such profoundly human activities, women have an aptitude that men may struggle to match.

When my wife recovered, and I had time to think – cancer had hijacked both our lives – I decided on transition. The qualities that were the best in me were the female ones, and I was done feeling ashamed of them.

Did your experience with cancer change your life in other ways?

Now I know how close death always is.

In ordinary life, ten years away seems as far off as never. And we always believe we’ve got at least another decade.

But having come that close to losing it all, having learned that time is always running out, I no longer care to live haphazardly.

How did your wife react to your transition?

Her response was, “Am I supposed to act surprised?”

She’s a gender-queer art school punk rocker, and I’m not her first girlfriend.

A good marriage is never easy, but the transition has made ours less difficult.

There are advantages to having a spouse who doesn’t think a woman’s feelings are irrational nonsense, and who can spend happy hours pawing through the sale racks at Nordstrom when the discounts are really deep.

So how does this fit in with translation of poetry by women?

At the centre is a desire to express my female nature.

I thought of hormone therapy and sex reassignment surgery, and maybe if I were twenty-seven instead of sixty-seven, I would have gone that route. But such modifications are, finally, cosmetic.

They couldn’t give me the girlhood I should have had.

I dress and present as female to the extent I plausibly can, which ends up being more rock ‘n’ roll androgynous than strictly female. But part of being a real woman is knowing what looks you can carry off and which ones you can’t.

I respect the choices of those who’ve taken it further than I: It’s kind of awful seeing someone you don’t want to be in the mirror. When I first started dressing as myself, I would look in the glass and for the first time in my life really breathe freely. I hadn’t realized that constant low-level anxiety isn’t part of normal living.

Now I go out in public as myself without much thought.

It’s much less daunting than I’d ever expected. For the most part, men don’t even see me: I’m a woman over 50, hence invisible.

It’s all sort of validating, in a slightly dispiritingly way.

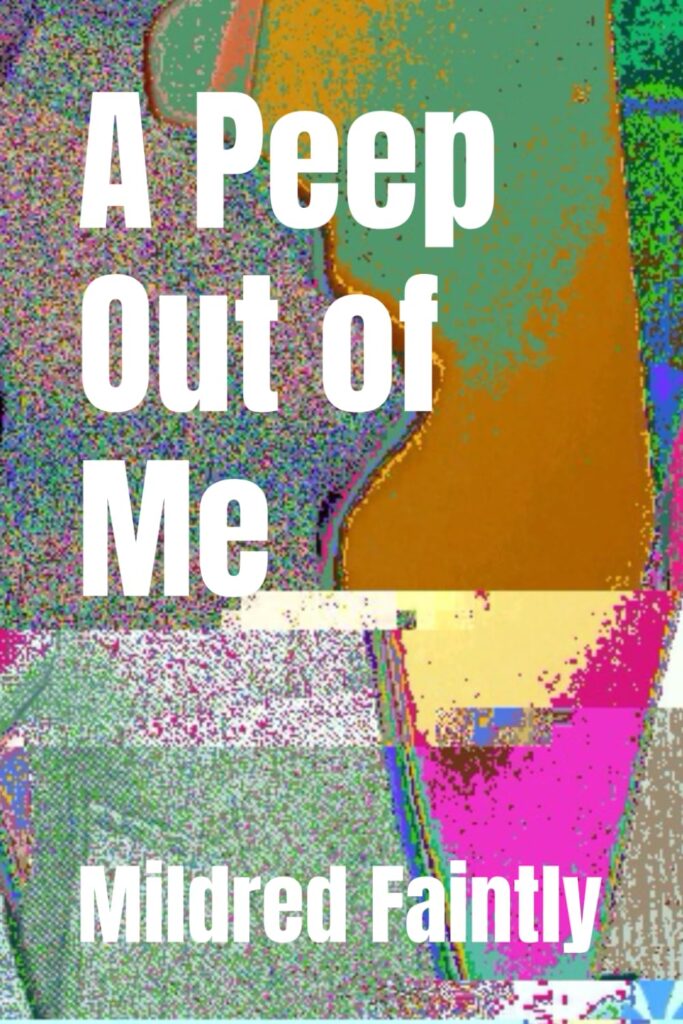

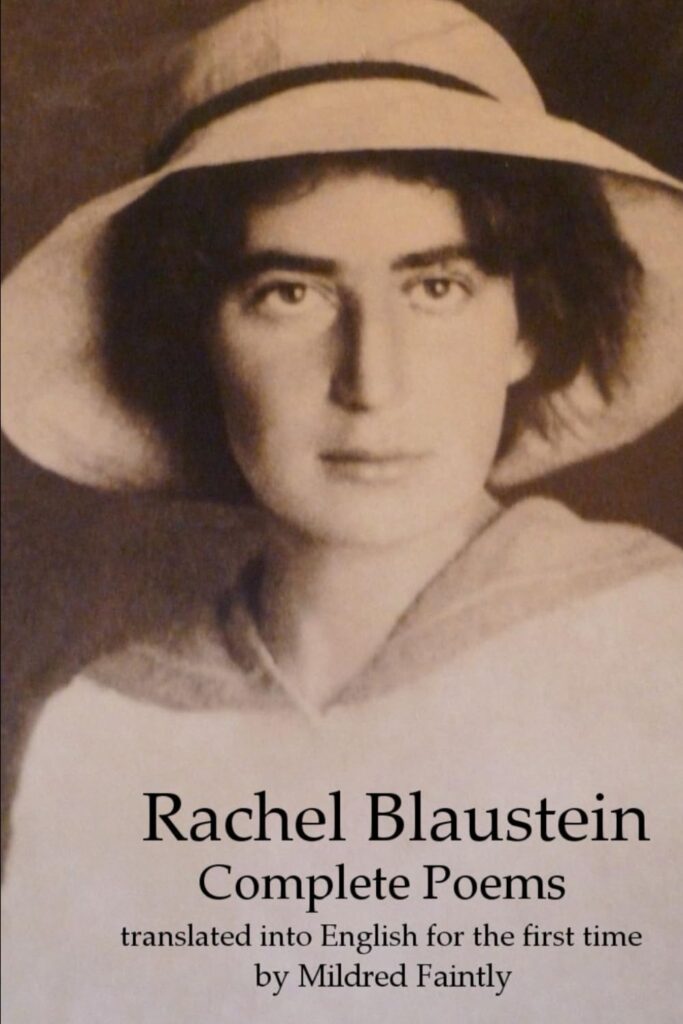

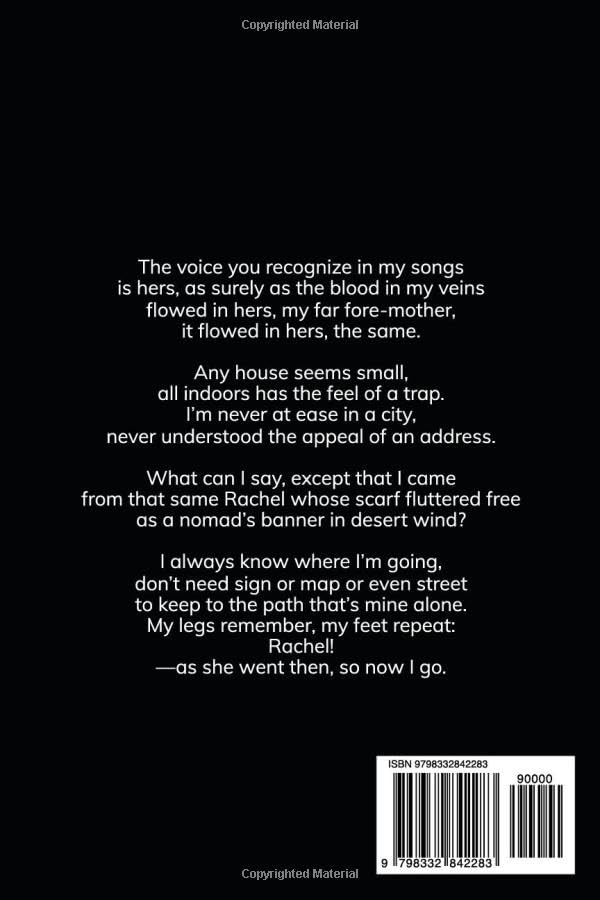

Published 2024.

With Rachel’s poems originally published in Russian or Hebrew.

And this relates to translating poetry…?

Ah yes. “Passing” wouldn’t have been the height of my ambition even if I could have managed it. Marooned in an alien gender for most of my life, I got a special kind of insight into gender identity – and an emulous admiration of women, like the longing of a moth for a star.

Wishing to redeem my experience, I decided to turn it to account by translating great poetry by women, thus writing myself into my authentic existence. And I hoped to translate women’s poetry with an empathy inaccessible to men.

Or, to put it more simply, if a little uncharitably – Like many a girl who discovers how plain she is, I realized I needed to become interesting.

With this healthy mixture of high and low motives, I embarked upon my project. I have some confidence in my poetic skills. I learned them from Allen Ginsberg

There’s a political element here as well.

Having been made to feel, life-long, that I deserved somehow to be punished for being a girl, I determined to help vindicate the dignity of women, which had been compromised so cruelly in me.

I want to earn my girlhood.

My dream is that other women will read my translations and say, “Only a woman could have understood that.”

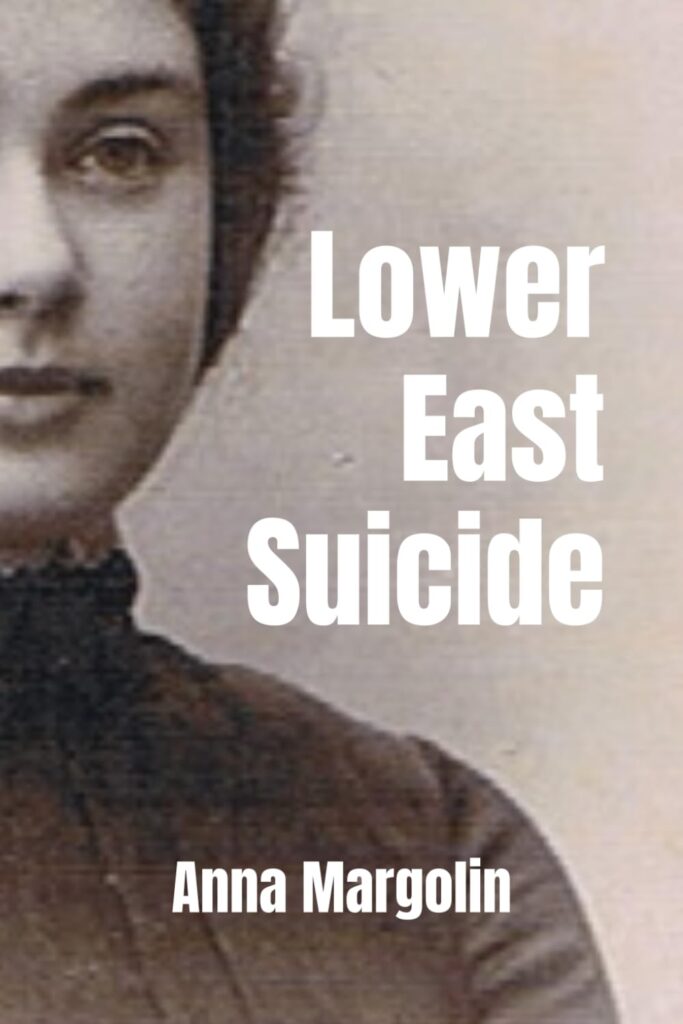

Published 2024.

Originally published 1929 in Yiddish.

You mention Allen Ginsberg.

How did he, or would he, have reacted to your gender identity?

Allen knew me as gay. Back then neither of us realized my closet had a closet. And that that closet was a big walk-in – More like an efficiency dungeonette!

Allen lacked all interest in women: to him they were invisible. And he didn’t much care for effeminate men, so the topic never came up.

Allen was one of the most selfless and saintly men I ever knew, but, like everyone else, he had failures of awareness.

Still, I’m sure Allen would have seen the humor and the rightness of it all.

If Allen taught me anything; it was to always be delighted by new insight.

What are you working on now?

Russians!

My Russian is finally good enough to translate Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsvetaeva. Theirs are the proudest most dazzling female voices the world has so far heard.

Is there a reason, in your opinion, that these supreme poets were both Russian?

Russia went from barbarism to the pinnacle of civilization – and back – in one hundred years, beginning with Pushkin and ended by Stalin.

Around the turn of the last century they absorbed in a single generation Symbolism, Expressionism, Cubism – the whole prism of isms. Because they were always outsiders, with an inferiority complex about western culture, they took what they learned utterly at face value, and literally did things Europeans only talked about. All of this was made madder and faster by a revolution bracketed by two world wars.

Akhmatova is the classic master of poetic form, a noble soul of instinctive dignity.

Tsvetaeva is the twisted sister, chanteuse of the lost cause – and one prefers her the same way one does Brian Jones to Jagger, Tom Paine to Jefferson, and Marlowe to Shakespeare.

Marlowe’s probably the aptest parallel, threatening the world with high astounding terms, Tsvetaeva’s the mistress of the “mightly line” which she delivers in the psychic Ray Bans and leather jacket of eternal adolescent rebellion.

Is there for you a more personal link to Tsvetaeva?

I feel I have a special connection to her world.

My grandparents on both sides were Jews from Russia. A thousand years there imbued my people with Russkaya dusha – Russian soul. Not an easy thing to define, but palpable in Tchaikovsky when Gergiev conducts.

And Tsvetaeva was a lesbian whose friends and lovers were Jews – a race whom the Tsar and his government officially hated. She rejected both the revolutionary and reactionary agenda, and so achieved an exile within her exile – that Paris of Russian university professors driving cabs and distinguished Russian poets waiting tables.

Tsvetaeva also wrote the greatest lesbian poems in the modern world, perhaps ever.

This was her cycle Podruga, (Girlfriend), the chronicle of her 1914 affair with Sophia Parnok, sometimes called “The Russian Sappho.” Herself a brilliant poet and the first “out” lesbian poet in Russian history.

My translation of the Tsvetaeva-Parnok poems is in the works.

As a transgender lesbian, rendered unemployable for all but the lowest jobs by a classics PhD, I think I “get” Tsvertaeva. My love for her began with the first of her poems I translated, ‘What it is to lose.’

It found a ready echo in my sad weird Russian-Jewish heart.

Comparing your translation of ‘What it is to lose’ with others, it’s hard to believe it’s the same poem!

How does that come about?

Most Russian poetry translations are by academics, like Elaine Feinstein. Having survived a doctoral program myself, I know how such training stamps the poetry right out of you.

You learn to dread making any assertion you can’t cite an authority in support of.

Thus academic translators are painfully faithful to the text – with reliably dull results.

With Tsvetaeva, it’s particularly disappointing. She writes elliptically, brilliantly expressing in a word what a lesser poet would say in a stanza.

The academic word-for-word approach to Tsvetaeva leaves unsaid all she brilliantly and unmistakably implies.

I don’t know of any Tsevataeva translation that isn’t hopelessly opaque in the literal way so esteemed by the tenured.

How was it your doctorate in Classics didn’t turn you into that kind of academic?

That’s what my thesis committee wondered.

But even if I’d been the sort of scholar they grant a doctorate without reluctance, I’d never have gotten better than the adjunct positions I held. The Humanities have been added to the evolution chart, the job I trained for ceased to be by the time I had the credentials – For me, an incredible stroke of luck!

Had I been hired on at Harvard I’d probably be drinking myself silly at the faculty club, sporting ratty tweeds and ill-considered beard. In my rare sober spells I’d be writing articles where every line floats above a fathom of footnotes – darning the socks, as it were, of classical philology.

Now, at sixty-seven, a self-made lesbian and twenty years sober, I can say that the torch passed to me by Ginsberg and Corso is one I never have suffered to gutter out. With no proper job or stable address for most of my life, and nobody but myself to please, I learned whatever languages I liked; wrote poetry on borrowed money and stolen time.

I’m content that I made the better speculation, the one Emily Dickinson declared, “beyond the broker’s insight,” for “slow gold, but everlasting.”

My devotion to poetry and learning have allowed me to speak with the tongues of Sappho and Tsvetaeva, which I think far finer than those of men and angels.

‘What it is to lose’, by Marina Tsvetaeva. Written in Paris; May 3, 1934.

Translated from Russian by Mildred Faintly.

I know what it is to lose . . .

I know what is it to lose one’s country.

The glamor and the bafflement of exile have passed.

The fact laid bare: I don’t care where I am.

Loneliness only

is my homeland now.

Does it matter what strange pavements I wander

clutching my sad little grocery bag,

back to a building that, like a hospital

or a barracks, could never be anyone’s home,

a place on which one leaves no trace,

that never knew you were there?

How should I care about my whereabouts

any more than a lion in a zoo

notes which faces watch her pace the cage,

captive hackles raised.

Red, reactionary –

can I care which group excludes me

drives me off, like always, into an inner world

peopled only by my feelings?

A Siberian bear, hunted from her glacier,

it’s all one to me who I fail to get along with

(or that I don’t even try),

Reduced to begging, do I care where?

I’m unseduced by the sound of Russian

calling to me with maternal sweetness

in the voice of a fellow-exile. What’s it matter

in what language I can’t be understood?

Here’s someone eager to speak, to ease

their indigestion, having greedily nursed

at the bosom of Mother Russia’s

expatriate press – pap of hopes and hearsay

“But you have to keep up with what’s happening!”

Go then, read your Times,

leave me to read the timeless.

I’m unmoved by news. Stunned and dumb

as a single tree-stump

left from the treelined approach

to an aristocrat’s sacked mansion

in my land where all’s been flattened

under an awful equality –

My history’s gone, every date effaced,

no more landmarks, no direction,

it’s like a single hand sufficed wiped it away.

I have no name, the place I was born

apparently never existed.

The frontiers failed and faded,

nothing defines me, and now not even

the most acute agent of the Soviet secret police

could find an incriminating trace

of nation staining my soul.

Every building feels weird to me now;

every church is empty, God turned out.

Nothing now’s not dully one

– unless perhaps, by the side of the road

I see a rowan, that pagan Slavic tree

magic and old before all history,

a tree that stands for a Russian eternity

even here, and even for me.

Links

- Mildred Faintly – 96th of October Author Page

- Mildred Faintly – GoodReads Entry

- Mildred Faintly – Amazon Author Page

- Mildred Faintly – 2024 Interview with Mildred, by Deborah Leipziger; via Jewish Women’s Archive

- Mildred Faintly – Three Poems By Chinese Writer Li Qing Zhao, Translated to English by Mildred, via The High Window Press

- Mildred Faintly – Facebook (private, for now)

- Jacob Rabinowitz – GoodReads Entry

- Jacob Rabinowitz – 2019 Review of ‘Blame It On Blake’ via The Allen Ginsberg Project

All images supplied by Th. or sourced online.