What would you consider the most dangerous book you have ever read?

Was it the atonal ultraviolence of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho desensitizing audiences to appalling acts of cruelty in the name of an ironic message?

Did you cautiously thumb through J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye with a vague notion that you may become a mindless assassin, or read George Orwell’s 1984 and feel radicalized against an oppressive system?

These kinds of books, all scathing fictions written by salacious thinkers, are premeditated to affect a change in the reader’s perspective, and to drive them a little mad with ideas they may not have come to alone. The same is true of dozens of influential writers, from the Gonzo-insanity of Hunter S. Thompson – Who inspired journalists to invoke a certain violence-of-thought in their work.

To the poetically irresponsible dope-musings of Burroughs, or de Quincy 60 years before – Inadvertently inspiring some readers to the depths of opiate-addiction to experience life the way these men had seen it.

But these are esoteric dangers; to risk their harm is to have misunderstood the underlying point many of these authors were hoping to inspire.

Some authors, however, mean harm. Some authors mean for their words to inspire acts of violence or revolt or criminality. Some aim to give instructions.

And more again simply regard knowledge as a reader’s responsibility to manage, regardless of the potential for harm to themselves or others.

In Clive Barker’s horror-novel Mister B. Gone, a demonic narrator linked inextricably to the advent of the printed word implores you from the second-person perspective to “Burn this book” in its opening lines, ostensibly to protect you – the reader – from unseen dangers in its pages.

An unknowable narrator pleads, bargains, cajoles, and threatens its own audience to free it of the responsibility of revealing its secrets. The book squarely places the onus of responsibility for ignoring explicit warnings upon the reader.

However, the world is rife with books containing dangerous text, instructions, or ideas, and the first consideration as to their purpose is that the authors intended for them to be read.

The reason why it was written is fairly-well that simple; instruction or inspiration, the goal is to be read and disseminated.

Who wrote the text, and to whom and how broadly they mean for it to be disseminated, become more specific factors worthy of consideration, and expose some of the greatest dangers with the existence of these works.

Early examples of books considered dangerous tend towards political or religious critiques. The first book banned in England was the anti-Catholic essay Apologie written by William of Orange.

Later examples tend to be works of violent extremism like the hateful white-supremacist terror-fantasy of William Pierce’s Turner Diaries, which is still widely available.

Governments have perpetually scrambled to control the flow of what they consider dangerous information, for good or ill, and since the proliferation of household internet across the world that has become a nigh-impossible task.

Legislation cannot compete with widely decentralized information hubs, the darkweb, roving skirmishes with freedom-of-information proponents, and the endless innovation of hardcore internet denizens.

Bans, Publishing Licenses, Copyright, and Public Domain / The Moral Imperative

There are a number of ways a book can be made unavailable, the very simplest of which is simply not to publish it.

This subjectively-managed method of gatekeeping and quality-controlling material puts the onus in the hands of publishers who can refuse to publish something off-colour or controversial because it may be unprofitable.

Committees and special interest groups have formed around this conceit, pushing for publishing standards and using the economics of supply and demand to enforce them.

Indeed, this is the method that brought the Comics Code Authority (CCA) to prominence in the late 1950s, after parents began to fear the popular boom in violent horror and action comics among their children.

The CCA set publishing standards upon comic makers and enforced them through a simple means – Via collective action. Parents would effectively boycott the makers of comics that did not adhere to the code, which would devastate their publisher’s financially and make selling comics in the US unviable.

This was so wide-spread and effective, most comics publishing outside of the United States stayed within similar guidelines to prevent controversy or boycotts in the US.

This is a kind of societal self-regulation and it is predicated on a financial-moral relationship, where the product is solely produced and distributed for profit.

This does not work where a work is flagrantly transgressive, and this has traditionally been a realm that underground comics have traded in since the advent of pulp press.

This failure is exemplified by the DC Comics imprint Vertigo, which traded sincerely on its refusal to adhere to the CCA guidelines and produced some of the most lauded and mature comics of the last 30 years – Including Sandman and Swamp Thing.

In recent years, the Comics Code Authority has gradually lost its clout against the changing market and you will no longer see the symbol adorning superhero books in comic stores.

The market has spoken.

Many texts that are written are never published, and where those items might be deemed “unpublishable” by modern legal standards, they still earn the ipso facto status of “published” by virtue of their dissemination through internet forums.

Fan-fiction is a valuable example, where works can represent anything from short stories to serialized tales featuring the trademarked characters of existing intellectual properties; without consideration to the owners of those properties. Many of these stories would be considered unpublishable for their crude or hypersexualized content, and the genre remains a fringe-concern.

However, the world is quite familiar with the story of Stephanie Meyers and her Twilight fan-fic becoming the literary juggernaut behind the 50 Shades of Gray franchise, seemingly legitimizing the genre as more than a cult-phenomenon.

That these kinds of works are legitimized in this way means their status as largely unprinted by established publishing houses is worth exploring. The fact of their status as “unpublishable” is frequently less to do with obscenity and more to do with the trademark and copyright issues that exist.

And so, their inability to be published is not for the public interest but to avoid litigation, embarrassment, and costs to the publishers.

That the market for this work is largely illegitimate does, however, seem to encourage a transgressive approach in some writers that would certainly press the nerves of obscenity and make good-taste blush.

Many of the earliest works to actually be banned in the modern sense, as they were considered dangerous by the body politic, were anti-Catholic texts which fomented protestant resistance in England and Europe. As it spread to US, the sentiment caused trouble and violence even in the distant colonies.

In England and France, William of Orange’s Apologie was considered an incendiary work of political and religious polarization. The text, which compiled existing arguments against the Catholic-led Inquisition across Europe, became part of the popular basis for the Dutch revolt of 1566 against the Catholic-supported Spanish.

In Catholic-ruled England, the text was banned outright to prevent consolidating criticisms of the Church or the Crown. In the colonies, Apologie was a formative inspiration for revolution against the Catholic Monarchy.

The Catholics became infamously comfortable of banning critical texts, particularly against a rising tide of fervent anti-Catholicism sweeping the world, with infamous anti-Catholic works like Master Key to Popery (1724) exposing hypocrisies within the clergy, and the sexually-explicit Awful Disclosures of Marie Monk (1836) fraudulently claiming to expose sexual abuse and child murder within a Canadian convent seeing bans in England despite their popularity among an increasingly literate and inquisitive population.

A similar controversy arose a year prior, with the publication of Six Months in a Convent, which falsely attributed stories of kidnapping and abuse to a small convent in Charlestown. The convent was targeted by an angry mob and burned to the ground, demonstrating the risk the Church may have feared all those years.

John Milton’s 1644 polemic on licensing and censorship, Apologie, fell afoul of the English monarchy, who regarded the seminal work on the right to free speech as dangerous to their interests.

Thomas Paine’s 1791 Rights of Man was explicitly supportive of the French Revolution and the sovereign rights of man to choose their representation. The work was deemed too dangerous to publish in England and Payne was tried for sedition by the Crown for fear that his work would spread revolution to British shores.

Fear of political or religious upheaval has been the inspiration for much of the censorship that governments have undertaken, however the inherent symbolism of books can sometimes inspire loftier forms of censorship.

The Nazis famously burned thousands of books critical of race theory and the National Socialist agenda in huge public bonfires where citizens were encouraged to throw offending materials on the flames themselves, which served the purpose of involving people in their own censorship; letting the populace take ownership of their ignorance for their own perceived good.

The spread of Marxist propaganda during the Cold War encouraged a bibliophobia of a kind, where people became deeply concerned by the perceived infiltration by agents of an ideologically monstrous enemy and the influencing works of writing and art they might disseminate through an unprepared, unprotected society.

There is a strong argument for Western capitalist propaganda existing simultaneously in far more overt ways, such as the distrust sown by McArthyism and Hollywood films acting as cultural and military propaganda overseas.

Nonetheless the Red Threat paranoia persisted and is evident today in attitudes towards socialism in US-centric developed nations.

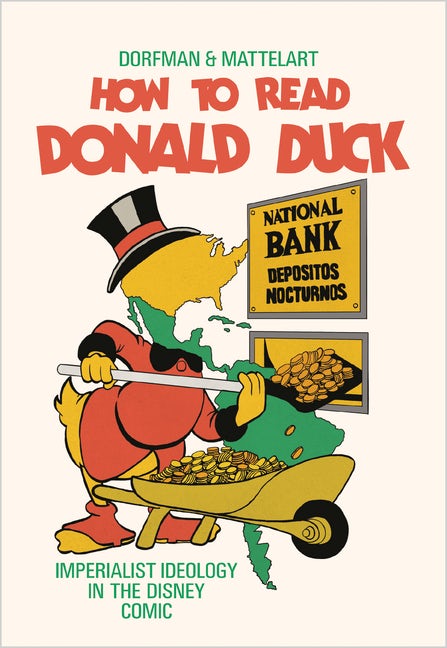

How To Read Donald Duck, a long-form 1971 essay by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart, is an interesting study in the banning of books to defend against the spread of Communism.

The essay critiques the hidden capitalistic influence of Disney comics from a Marxist perspective and is considered a seminal work in Latin America, whose influence has spread to economic and political reformists around the world.

The book was a massive success upon release, however with the installation of American-backed dictator Augusto Pinochet the book was swiftly banned.

The book remained illegal to print or sell in Chile until the end of Pinochet’s rule in 1990 and the authors were exiled from Chile.

Concurrent with the war on Communism, there was a focus on eradicating what was considered deviant thinking. The logic so frequently asserted was that the Marxist enemy was attempting to compromise free-thinking citizens’ moral logic and tolerance for Marxism.

As such, “obscenity” became the buzz-word of public protection.

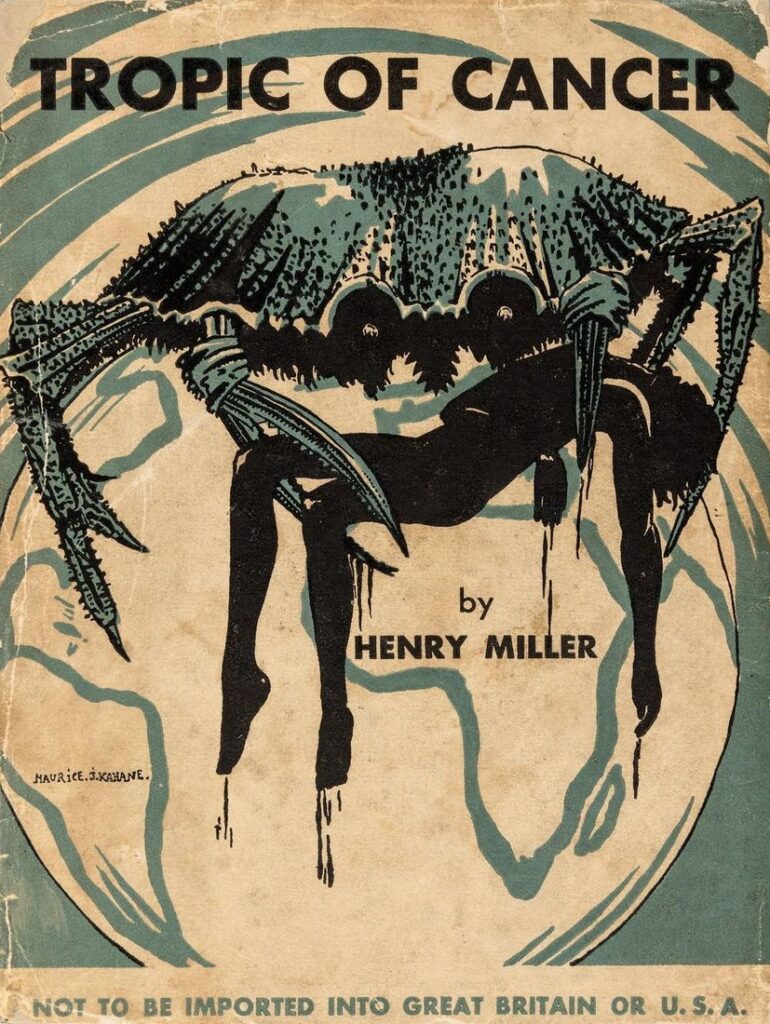

Henry Miller’s controversy-soaked classic Tropic of Cancer, published in 1961, landed at the zenith of this witch hunt. The book broke with literary tradition and has since been lauded as one of the great American novels, however upon its release it triggered a series of obscenity trials in the US which helped shape freedom of speech laws for the decades to come.

Ultimately, the book’s legitimacy wrested on whether it had redeeming social value, which is in practice an unusually subjective bar to surpass but, thankfully for the annals of literature, the book was deemed to have literary value that separated it from pornography.

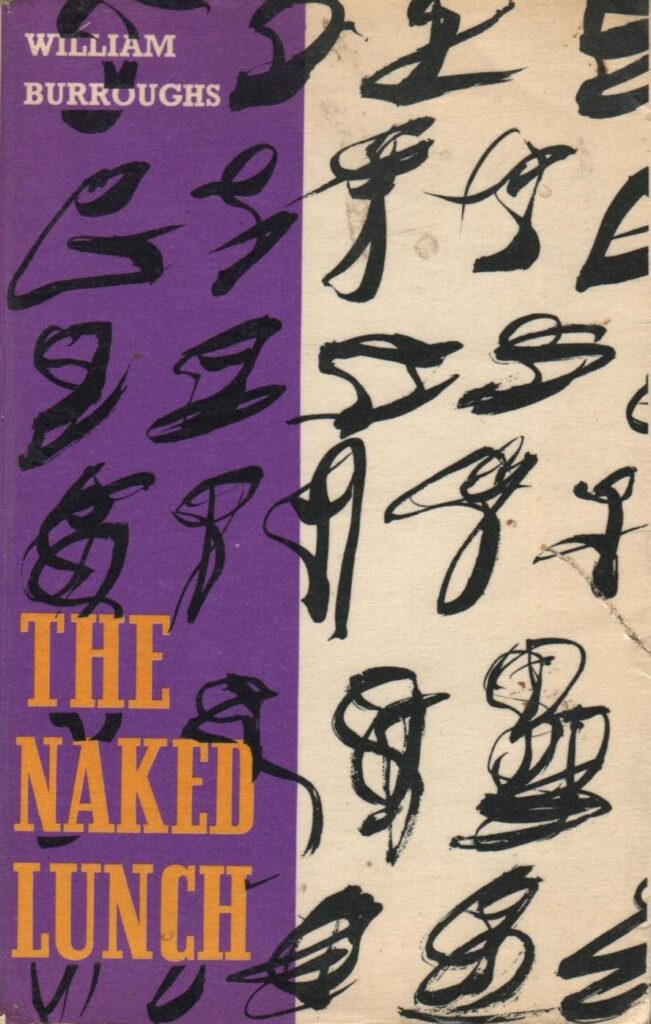

Beat author William S. Burroughs found himself subject to similar attention for the publication of his canonical work Naked Lunch, seeing the book banned in several US cities in 1962 but ultimately skirting the same degree of publicity as Miller the previous year.

Nonetheless, Burroughs earned a place as a controversial figurehead of the Beat movement with his explicit and hallucinatory depictions of sex, drugs, violence, and mental illness as his books seemed designed to invite conflict and negative attention.

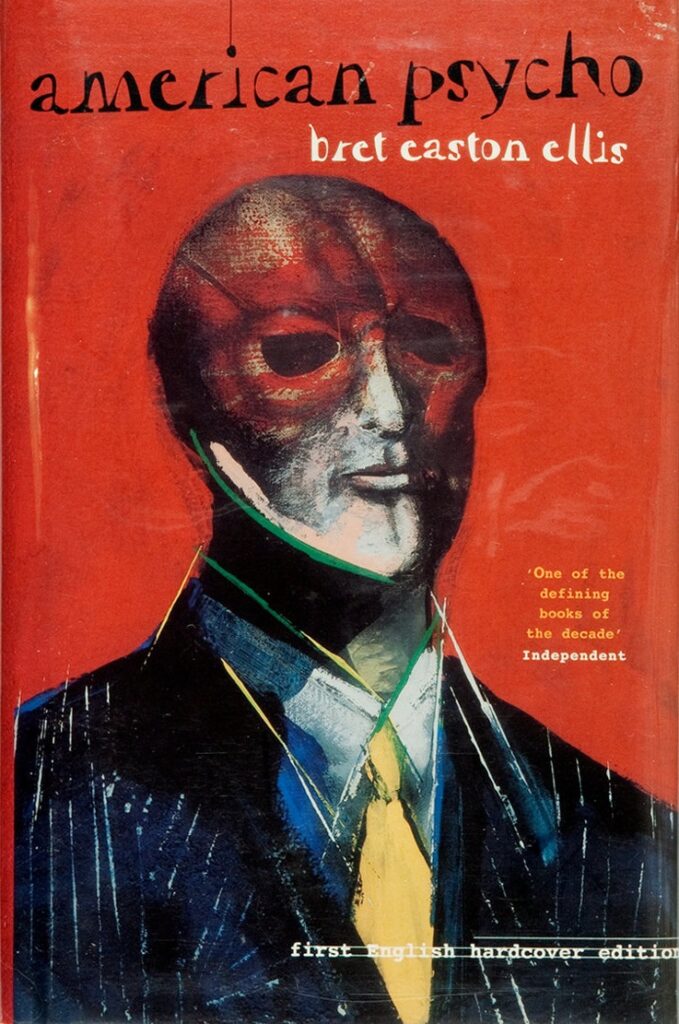

A closer-to-home example to look at is the banning of Bret Easton Ellis’s modern psychological horror-satire, American Psycho, which was banned for some years in the Australian state of Queensland for obscenity but nowhere else in the effectively-borderless country – Creating an oddly unmanageable grey-market in the sale of copies purchased in other states where its sale was at least somewhat regulated by parents and responsible retailers.

As such, I was personally able to purchase a copy from a Queensland street market at the age of 14, roundly circumventing the ban that existed at the time with no fanfare or trouble whatsoever.

Some other works which are considered Western literary canon have been subject to various bans and attempted bans to avoid inflaming racial sensibilities.

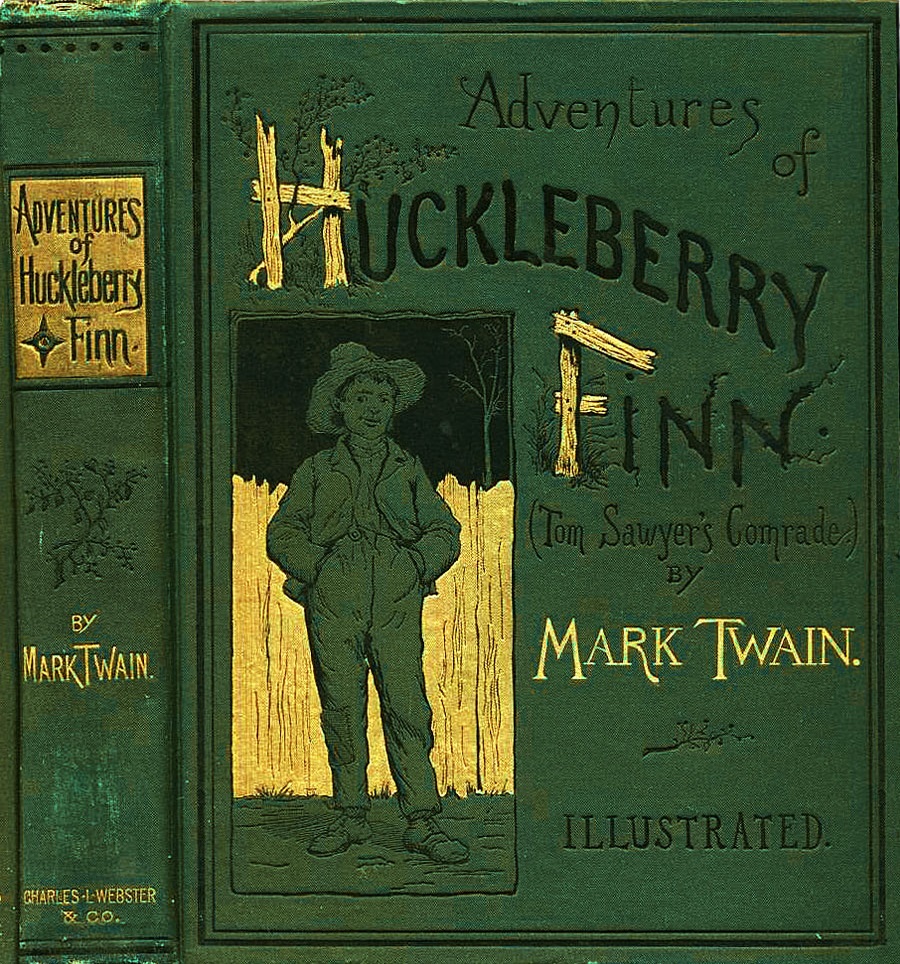

Mark Twain’s famous boys’ adventure tale The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been subject to various attempts to ban it or remove it from schools and libraries for its insensitive racist language and depictions of racial stereotypes.

Nevertheless, over 100 years after its publication it endures as a part of the American Canon, although its modern legacy is regarded as significantly problematic.

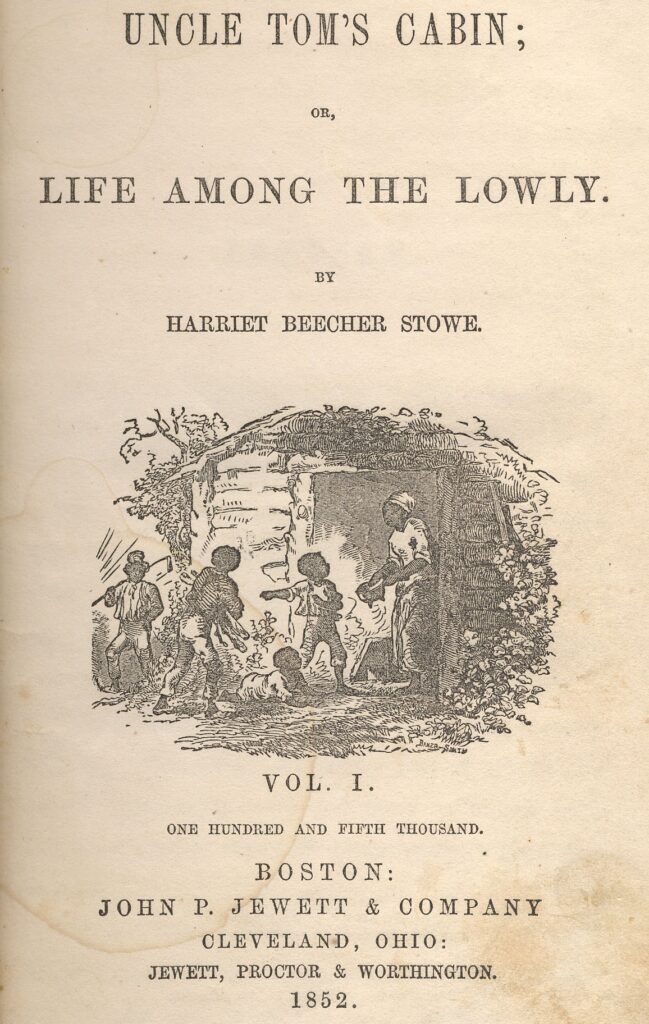

Uncle Tom’s Cabin by schoolteacher and abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe represents a unique counter-example. Published in 1852, the novel was a rich anti-slavery tale showing the atrocities and hardships of slavery and illuminating abolitionist politics.

The book became an influence on the anti-slavery movement which led to the American Civil War, and helped inspire countless slaves to flee servitude and take the Underground Railroad north. Anecdotally, there are suggestions that it was the very first book many African American people learned to read when education was not a condition of chattel-slavery – Where even the Bible had previously only been recounted to them by pastors or masters.

In response to its inflammatory influence in the South, the book was banned in Confederate states to help stem the abolitionist revolt.

Each of these books represents an attempt to create a beta-break in their form, either literary or political.

These books can be looked at as examples of people attempting to improve society, in their acute ways and having their ideas suppressed for the good of specific and limited bodies or factions – A government, a church, a wowser or a prude.

What then of the books that are not written with the best of intentions?

Dangerous Ideas

Arguably the most dangerous texts of the 20th century were those that fed the eugenics movement, anti-Semitism, and bellicose European nationalism.

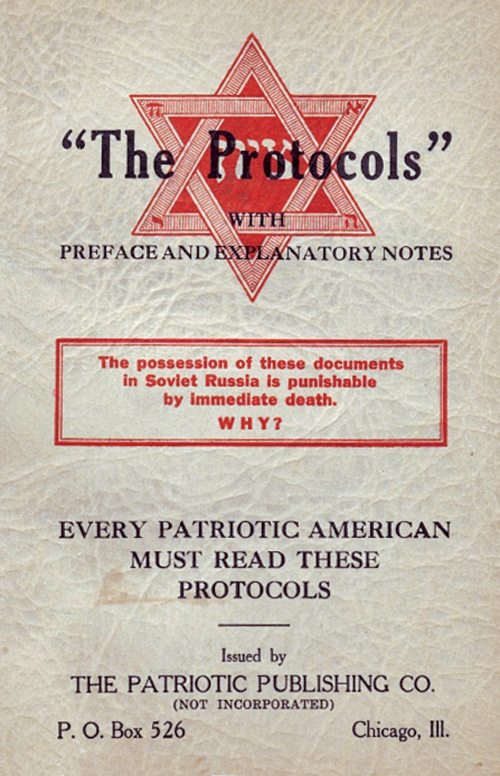

Among the most infamous of these was the Russian anti-Semitic hoax-essay The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which purported to expose the alleged plan for ethnocentric world domination being enacted by the Jewish population of Europe through political and financial influence.

These conspiracies, first published in English in 1919 and soon printed en masse in America by none other than industrialist Henry Ford, will sound familiar even today to anyone who has encountered one of the persistent and prevailing myths of secretive Jewish cabals holding influence over a New World Order – The Rothschild’s, Zion, and Freemasons moving in secret in the halls of power are old stories that have lasted far past the point they should have lost their credibility and mystery.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, thanks in part to its broad dissemination in 1920s America, is the source of much of this conspiracy thinking – Even nearly a century since the text was exposed as bunkum.

The European inter-war period was ripe for political pamphleteering and rapidly increasing literacy invited more proletariat thinkers to write for their people.

This period gave rise to a great deal of political theory, surrounding in particular notions of industrial cooperation, nationalism, economic revolution, and the changing face of European secularism.

Many works from this broiling period of political thought are still cited today as seminal academic writing, and any study of the period between the First and Second World Wars will demonstrate Western Europe in particular as a bubbling melting-pot of revolutionary action inspired by those ideas.

This was, of course, part of the climate that fed the intensity of the Spanish Civil War and WWII.

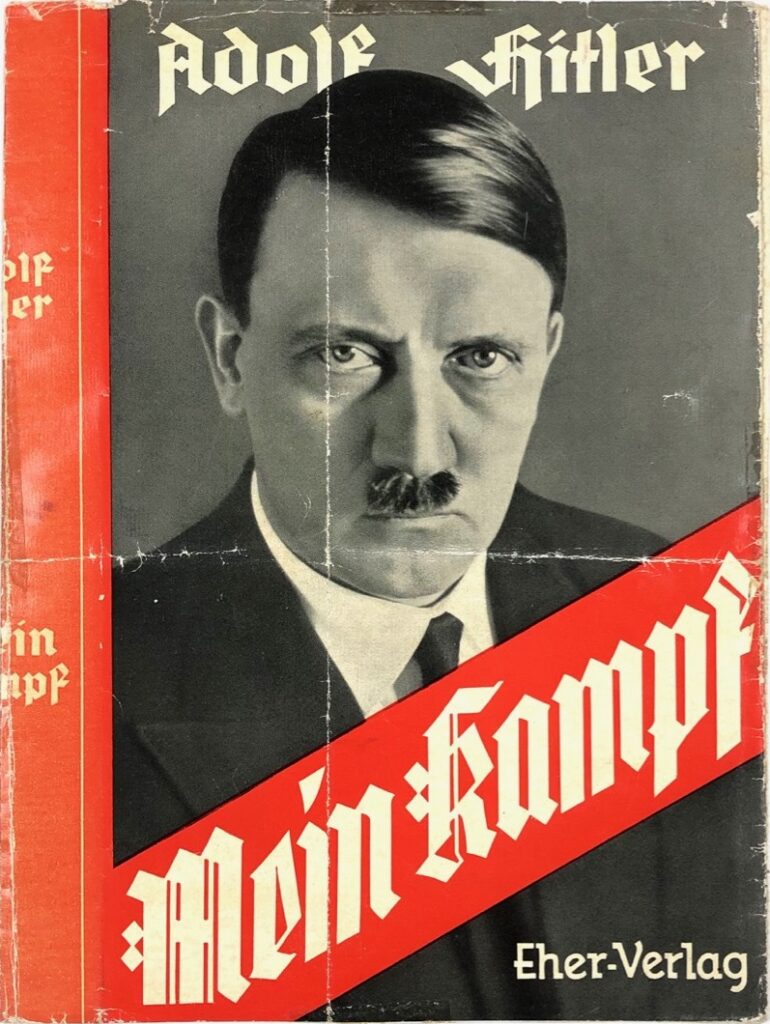

We cannot speak about dangerous books of the 20th century without looking at Adolf Hitler’s violently nationalist 1925 book Mein Kampf. The book was written while Hitler was a prisoner and its ideas helped spur the German people into a strange and fervent kind of nationalism that – with the Nazi Party’s spectacularly nasty politicking bringing them to within reach of the Chancellorship – nearly broke Europe by the end of the 1930s.

Mein Kampf’s copyright was held by the state of Bavaria after Hitler’s suicide in 1945, and the state agreed not to allow the book’s publication or sale in Germany.

However, copyrights in wartime are a funny thing…

The US Government had previously seized the right to copy Mein Kampf in 1942 under the Trading With The Enemy Act of 1917. France had allowed publication of a copy, distributed as a warning of Nazi doctrine to a largely liberal and unaware French populace, in 1934, where Hitler successfully sued for copyright infringement – Proving that even in wartime, civil tort laws can be a sharp sword. Copies have been printed and distributed around the world, and the book is commonly available in libraries, even in Germany, albeit often in edited or heavily-annotated forms.

Few efforts have been made internationally to prevent the sale of the book, and possessing it is not criminalized. Rather, the book is looked at as an important academic resource – something of a window into the dark heart of nationalism and anti-Semitism – and even Jewish scholars have defended the book’s publication as a means to teach and inform.

Although not all of the book’s sales can be safely attributed to scholastic pursuits and a quest for knowledge.

Sales of the book continue unabated, with thousands of copies being sold a year in the US and having made national bestsellers lists in Turkey as recently as 2005.

This brings to the fore the question of where the line is for censorship, and what are the commensurate levels of understanding and prior knowledge to properly and safely understand a text with such incredibly dangerous themes and potentially-radicalizing effects as Mein Kampf?

Although uniquely notorious, Mein Kampf is not unique for its poisonous worldview, nor is the West exempt from the influences of hateful prose disseminated among an increasingly connected and wary society.

The United States, who had been the loudest defenders of multiculturalism and democracy in the early 20th century, bore a roiling undercurrent of racist literature informed equally by segregationist politics, eugenics theory, economic privilege, and Aryan anti-Semitism after the war.

White supremacy smoldered away like an ugly little ember in the fabric of America and it bred a violent kind of fantasy-building, exemplified by the now-infamous Turner Diaries by American neo-Nazi William Luther Pierce.

The book is a fictional work depicting a revolt by white American citizens against the US Government, an apocalyptic race war, and the nuclear annihilation of almost everyone except the protagonists and the most violently hardcore or racially pure of their political allies and enemies to create an international segregated utopia.

The Turner Diaries acts as more than just a work of hateful fantasy fiction, but instead includes expansive passages describing the methods and theories of terrorism, almost as an instructional guide, as well as crystallizing a worldview of extreme eugenic theory and racial violence that culminates in the narrative with a horrific pogrom of genocide called the “Day of the Rope”, where white citizens begin murdering and lynching Black citizens, hanging their bodies from bridges and lamp-posts.

This phrase may have become familiar to people in the most incendiary months of 2020 as the Black Lives Matter movement met its seditious counter in the white supremacist movement who began ‘predicting’ the impending outbreak of “Day of the Rope” style retribution against Black Americans.

It became clear that the work of Pierce had circulated far beyond the reach of its book-sales and had become symbolic of a larger anti-Government agenda for violent nationalists, Libertarians, and racists alike.

The line between these factions has, expectedly, become quite blurred, as exemplified by the Boogaloo Boys; a violent anti-Government protest organization that emerged during the BLM protests with a distinctive paramilitary-cum-luau uniform and notions of instigating a war along pro-and-anti-government lines.

Implicit to this mission was an effort to create a volatile race war with a zero-hour designation of “Day of the Rope”, lifted straight from Pierce’s violently racist novel. They clamored online to see the first day of conflict, and some reports of violence during this time suggest that some people may have indeed attempted to instigate the first day of a Turner Diaries-style racial Armageddon as Black people were found lynched and hung from overpasses and trees in some luckily-isolated events in the hottest months of 2020.

The book, while certainly deserving of its notoriety on that basis alone, holds another horrific shadow beneath its deranged pages: Timothy McVeigh.

McVeigh was the Oklahoma City Bomber, one of America’s most frightening domestic terrorists. His bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in 1995, killing over 150 people and injuring nearly 700 more, was inspired largely by his growing radicalization against the Government after the Waco siege in 1993.

McVeigh was known to be a fan of The Turner Diaries, inspired by its focus on firearms and urban terrorist tactics. After the attack, photocopied pages from the book – specifically depicting an attack against the US Capitol – were found in an envelope in McVeigh’s car, left as a kind of manifesto and firmly linking the bombing to the message of the book.

The Turner Diaries, despite its outsized influence on racial violence and domestic terrorism, remains widely available. The book was available on Amazon as recently as January 2021, although has since been dropped from their catalogues in a recent purge of books associated with the QAnon movement, whose adherents stormed the US Capitol in a violent and seditious riot on January 6 – Which is an unmissable coincidence.

Moral Resistors & Dangerous Knowledge

A further study worth looking at, inevitably, is The Anarchist Cookbook, published in 1971 and written by William Powell under the pseudonym “The Jolly Roger”.

The book was a collection of recipes and instructions for bomb-making, improvised weapons, and drug manufacture, all prefaced by the author’s views on anarchist politics and his belief in the need for regular citizens to prepare to overthrow a tyrannical or corrupt government and resist social and economic extremism such as Communism.

It has earned its notoriety by being present at the scene of countless explosions from successful and unsuccessful attempts to follow the books instructions for bomb-making and drug-manufacture, although the efficacy – and indeed safety – of many of the book’s recipes is questionable at best. The book is infamous among young psychonauts for its laughable suggestions on how to produce drugs, including one called “Bananadyne” which is made by scraping the innards of a banana peel to dry and smoke the contents.

This will, of course, have no psychoactive effect whatsoever, but teenagers are nothing if not curious.

The Turner Diaries provide instructions for planning and enacting a terrorist attack and various crimes surrounding the successful execution of evil ideas laid out in a polemic-narrative fashion. It conceals the instructional purpose of the book behind a narrative prose and philosophical exultation into a kind of clarion call to the extreme Right. But it is clear enough in its context – That of a violent revolutionary text.

The book tells you “why”, not just “how”.

And while the pages of The Anarchist Cookbook are not muddied by narrative, the book is clear in its motivations. There are explicit ethical-moral suggestions to the work and their creation, questionable as they are, and there is no clear way to use the information contained for the betterment of the reader or society at large unless one adheres to the morals of the book.

Is there an ethical difference in publishing books that omit the “why” and simply instruct on “how”? Is it better that a book should not attempt to affect your motivations but rather simply instruct on how to safely achieve a goal?

Where do we draw the line on morality informing education?

Here, we turn to look at the most strictly-illegal form of dangerous book in most jurisdictions and the one with the greatest level of common notoriety: illicit manufacturing guides.

The rabbit-hole of illicit manufacturing guides goes incredibly deep. Beyond the nascent and largely-ineffective urban terrorism module that is The Anarchist Cookbook is a raft of books written by technically-proficient lunatics with an acute ethic of educational anarchism informing their work.

No good can come from these works, but the authors never once suggest that it would.

Caveat emptor.

Drug and bomb manufacture – books found on the shelves of drug chemists – are not mysterious, exclusive, or difficult to find. Many of them are available online, both to purchase or in PDF format for free download, although the legalities and ethical implications should rightfully discourage one from doing so.

In Australia, laws banning books that promote, incite, or instruct in criminal matters prevent the sale of many of this type of book, but again they are still widely available online and through overseas booksellers.

One of the more infamous examples in Australia is How to Make Disposable Silencers by Desert and Eliezer Flores.

The book, published in 1984, was very simply an illustrated guide to the manufacture of muzzle-suppressors, misleadingly called “silencers”, for guns (make no mistake, guns remain quite loud even with a properly made suppressor). Caught by the comprehensive laws to prevent the sale or possession of books that instruct in criminal methods, the book is rightfully banned as its educational value to the public is nil and the implications of owning it are inescapably criminal and likely pointless (see note about suppressors not making guns silent).

Nonetheless, anyone seeking a copy need only consult the internet with a decent VPN enabled. Once again, I must stress that doing so is a very bad idea for a multitude of legal and moral reasons.

Similarly, no vested moral interests save eco-terrorism instructional manual Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching from its legal and ethical criticisms.

A violently revolutionary manual for aspiring eco-terrorists, the book is clear on its motivations: to teach how to use saboteur tactics and direct action to halt the march of environmental carnage.

A loose distillation of guerilla warfare techniques and protest tactics, the guide includes instructions on how to booby-trap environments to make logging or clear-felling too dangerous to complete, and how to maximize the efficacy of blockades.

Although the fact of its activism-theme separates it from such bluntly amoral criminal works as How To Make Disposable Silencers, the book is nonetheless a clearly-phrased call to violent terrorism. It is banned under the same laws as most of the books mentioned in this section, although once again it is easily accessible with a nominal amount of searching online.

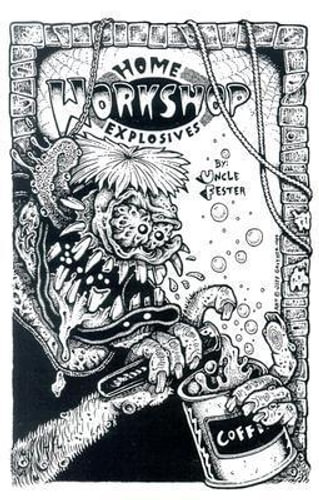

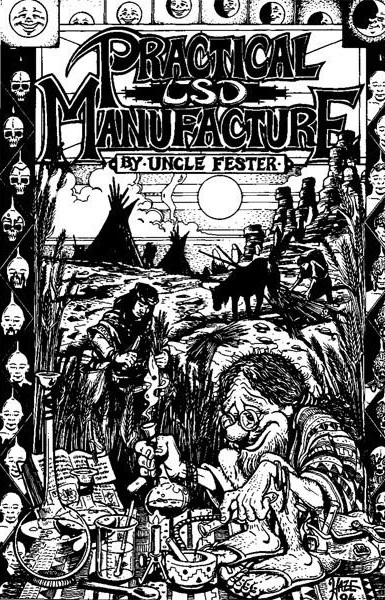

Among the better-known and more vitally dangerous authors to produce works in this oeuvre is an underground chemist named Steve Preisler, who published extremely accurate guides to drug, explosive, and poison manufacture under the nickname “Uncle Fester” during the 1980s.

The “Uncle Fester” books are detailed, illustrated instructions for making some of the most dangerous and volatile chemical compounds ever introduced to the criminal underground.

His first book, Secrets of Methamphetamine Manufacture, was written in prison on a borrowed type-writer after several arrests for possession of methamphetamine. The book contains instructions on how to make methamphetamine, as well as necessary precursor chemicals and associated stimulant-class drugs such as MDMA and MDA.

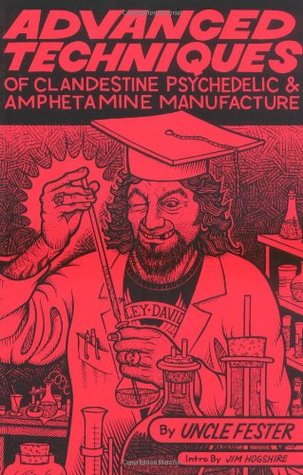

He followed up the success of this book with six more books instructing in how to make explosives (Home Workshop Explosives), poisons and nerve gases (Silent Death), armor-piercing bullets (Vest Busters), LSD (Practical LSD Manufacture), as well as a supplemental book on drug manufacture (Advanced Techniques of Clandestine Psychedelic & Amphetamine Manufacture) and one simply on how to kill a man with a knife (Bloody Brazilian Knife Fightin’ Techniques).

The knowledge contained in his works is of little legitimate value to law-abiding citizens and there are few justifiable reasons to know the contents of these combined books.

That makes it all the more curious that so many of the more dangerous and notorious “greatest hits” described in these books are so prominently featured throughout the hit television series Breaking Bad.

Whether coincidence or deeply-layered research to which the showrunners have never publicly alluded, the show features recipes prominently featured in the Uncle Fester books as key plot-points, including the use of thermite to melt steel, the use of blue methylamine precursor to make methamphetamine, and the use of ricin as an indetectable poison; each of these recipes is described in one of Uncle Fester’s worryingly practical books.

In 1991, a 66-year old organic chemist named Alexander Shulgin wrote a guide to drug-making with the effusive title PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story (or Phenethylamines I Have Known And Loved). Written in two parts, the first concerns a fictionalized autobiography implying the merits of psychedelic psychopharmacology, or the use of psychedelics in psychotherapy.

The second was a detailed guide to the production of 179 different illegal psychedelic compounds derived from phenethylamines, including all of the synthetic amphetamines today, many of which had never been synthesized before.

The book contributed dozens of new drugs to the street market as the means of making them came into reach of even average chemists.

The method for production of MDMA is among the most common processes used by clandestine chemists and the book is purported by law enforcement to be a common addition to most illegal drug labs seized by authorities.

Shulgin, during his decades of research, had introduced MDMA – now an extremely popular street drug – into the psychiatric field in 1971 but it wasn’t until his first book was published that the rush to flood the party-drug scene with newly-minted Ecstasy tablets took hold, ushering in cultural touchstones such as the UK’s “Summer of Love” and the 90s rave scene.

Along with a new roster of worldwide organized drug traffickers for authorities to contend.

Many more of his synthesized drugs have found their way into the public consciousness, particularly after the publication of his second book TiHKAL (or Tryptamines I Have Known And Loved), which describes the synthesis of 55 more illegal drugs, this time derived from tryptamine compounds and including wildly popular chemicals such as DMT, LSD, the sleep-chemical Melatonin, and dozens more extremely powerful and unique hallucinogens.

These books broad illegality in jurisdictions like Australia do not prevent them being accessible. Worse and more complicated, there are real academic merits to these books in particular – above those of Uncle Fester – as many of the syntheses described are unique to Shulgin’s lifetime of work in the field of organic chemistry.

The books remain easily available, although their availability is simplified somewhat further by Shulgin publishing the synthesis portions of his books to online drug resource Erowid.

The books can be purchased without much trouble, although once again there are legal and ethical liabilities which should prevent those without nefarious or legitimate academic interests from risking it.

Academic interests run deep in universities, thinktanks, and research institutes. The field of organic chemistry, to which Shulgin dedicated his entire professional life, is inarguably expanded for allowing his work to be seen and disseminated among students and professional chemists.

However, by virtue of its availability to students and researchers, books cannot effectively be banned, only restricted, and thanks largely to its unique academic status and a general sense of democracy in the sciences, it is unconscionable to many that laws would prevent new scientists in the field to access the work of previous giants based on its potential to be misused by criminals and laymen.

The notion that a work, no matter how obscurely niche or inaccessibly difficult the subject might be is a prevalent notion in deciding contested or banned books.

The severely-reduced audience for some books prevents their wide dissemination – However they still find their target audience and due to complicated real-world legalities sometimes the repercussions are far-reaching.

The Peaceful Pill Handbook, a euthanasia guide published in 2006, largely ignores the explicit politics of the topic and simply instructs the reader on the best methods to achieve success, assuming some level of prior interest or knowledge.

The authors were unlikely to conceive of somebody who is completely healthy attempting to follow the instructions contained.

There is no debate about the moral imperative behind euthanasia, instead simply providing basic instructions for those wishing to skirt existing laws and use a perceived “best practice” method for at-home assisted-suicide or voluntary euthanasia.

Despite its deeply controversial, morally oblique, and legally fraught content, the book has received minimal attempts at restriction. The book has been refused classification in Australia, after initially being published with age restrictions, and has been banned in New Zealand, but remains freely available online and from international booksellers.

The book makes no argument for suicide or euthanasia and does not encourage readers to partake in the act. It is designed as a clinically dry instructional guide for people who are already exploring the fateful choice.

The argument for preventing the instruction of criminal acts in this specific context is undermined somewhat by the severity of the choice that has come before it. Nonetheless the book is rendered illegal under the same laws that have seen A Field Guide To Monkeywrenching and TiHKAL prohibited here.

The controversy surrounding The Peaceful Pill Handbook’s reclassification and banning in 2007, after being available to purchase legally for the previous year, helped spark a new round of debates concerning the legality of euthanasia in Australia and New Zealand at the time. The debate has cooled significantly in Australia.

However, in 2020 New Zealand citizens voted to legalize euthanasia in a national referendum known as the End Of Life Choice referendum.

It could be argued that, due to its part in the discourse surrounding the politics of Australian euthanasia debate, the book might retain a significant critical value for sociology academics and legal scholars.

Further, in the case of New Zealand, it could be argued that euthanasia’s change of legal status might preclude the moral necessity of prohibiting the book altogether.

Conclusion

The complexities surrounding the publication of these variously seminal and uniquely transgressive works are as deep and ethically-corrupting as the contents of the books themselves – Where knowledge is the sacrifice and criminality is the pre-ordained and inevitable result.

With no way to stop materials being published and spread on the internet, the only viable way to ban these materials is to criminalize their possession. This comes with significant practical problems and brings to mind loose implications of criminalizing “thought-crime”, a line most governments are wary of crossing so blatantly as to employ search-and-seizure warrants to find copies of non-approved books. A trope common to dystopian science fiction such as Ray Bradbury’s nightmarish classic Fahrenheit 451.

As such, authorities locating copies of these books is a matter of pure chance, where a copy might be located in a criminal search or accidentally discovered in transit by Australian Customs, and punishing their possession is uncommon at best without other associated crimes indicating some intent to misuse the information contained.

Instead, authorities and moral guardians are reliant on natural defenses to the curiosity of unscrupulous people; that is, the natural imperative to goodness that most people display that prevents them from needing to ever know how to make a pipe-bomb or 30-hour-duration hallucinogens; or to kill a human with castor beans – And the acute complexity of learning distilled sciences or political theory from standalone texts that prevents most people from criminalizing and radicalizing themselves that way.

Some level of prior knowledge is assumed for many of these books, which limits some accessibility – A layman would have no conceivable way of understanding the syntheses described by Shulgin.

Very few people will ever have a pressing need to understand the political psychosis of violent racists or the detailed summations of drug manufacture other than those who might wish to study them, for good or ill.

And therein lies the rub; academia is a shared resource and much of the information available in these problematic books is available in other forms and other books, if somewhat less accessibly. There is no hope of ever removing the knowledge from the academic consciousness, only limiting its availability only to those who wish to find it.

Even a work of insane fiction like The Turner Diaries has earned some level of academic speculation thanks to its heartbreaking associations with White extremism – A topic worthy of deep study and critical analysis. The book, objectively evil as it is, cannot effectively be removed from the public consciousness even by some miracle of internet-cleansing without compromising the important academic annals that have been written about its associations to real-world violence.

That depth of academic and critical value limits the overall pursuit to control the flow of this kind of information.

In spite of the controversies and often-sound reasonings behind their various statuses as banned, problematic, unpublished, contested, or otherwise dangerous books; each of these works is accessible with a minimum of fuss and the risks around their legality is primarily with regards to their use or misuse, as the case may be.

Human ingenuity is, as ever, the real danger.

Reader beware.

Article art by Dan Thrax.