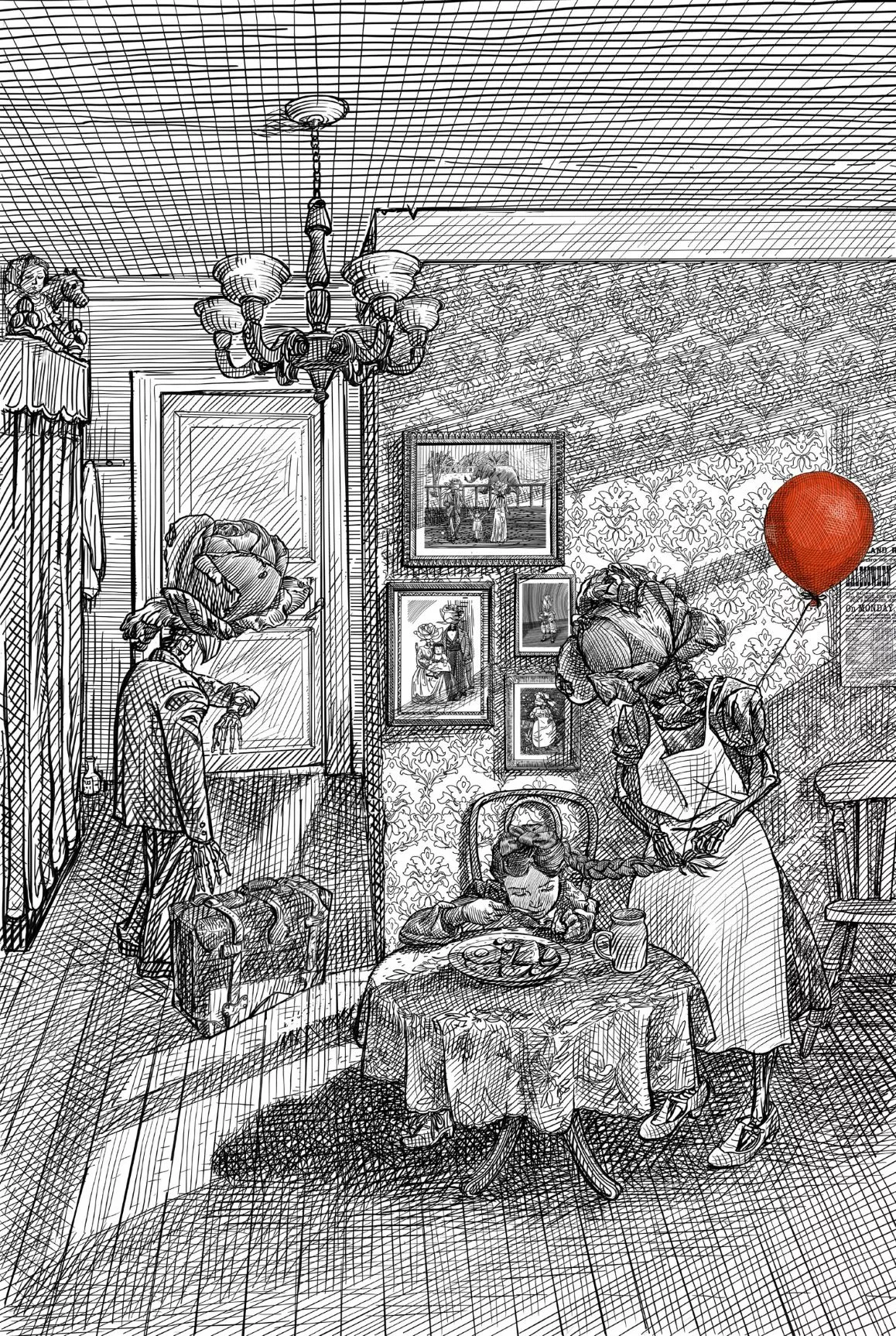

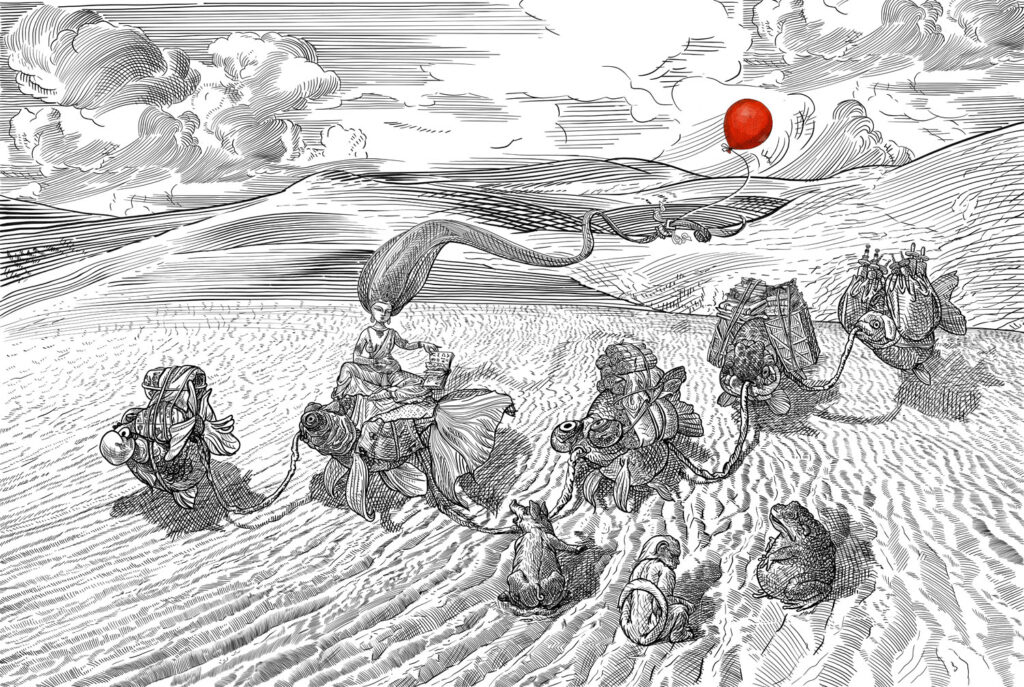

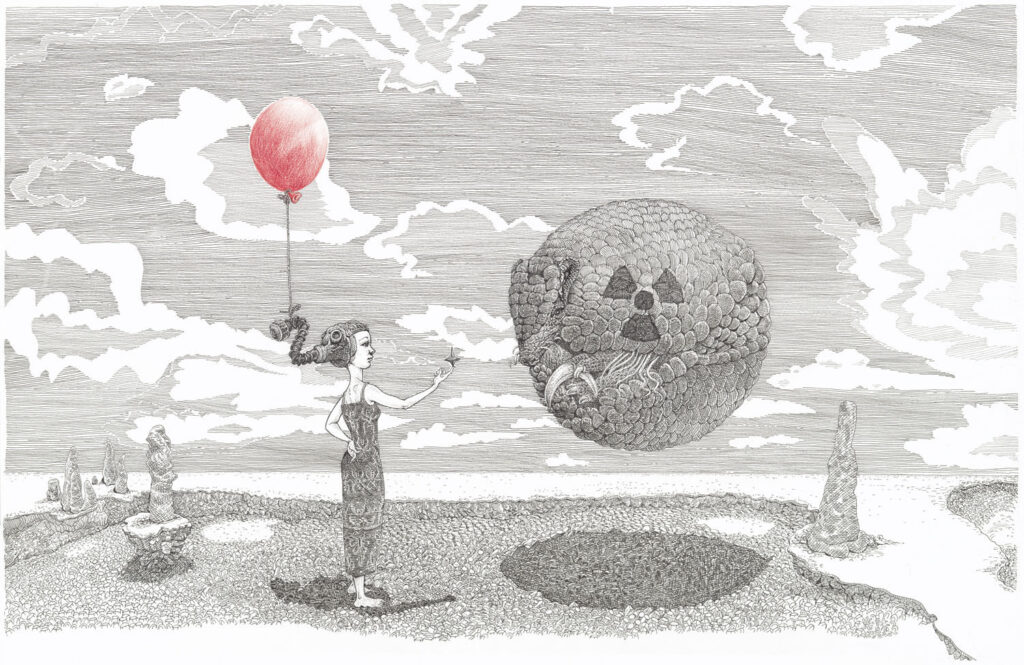

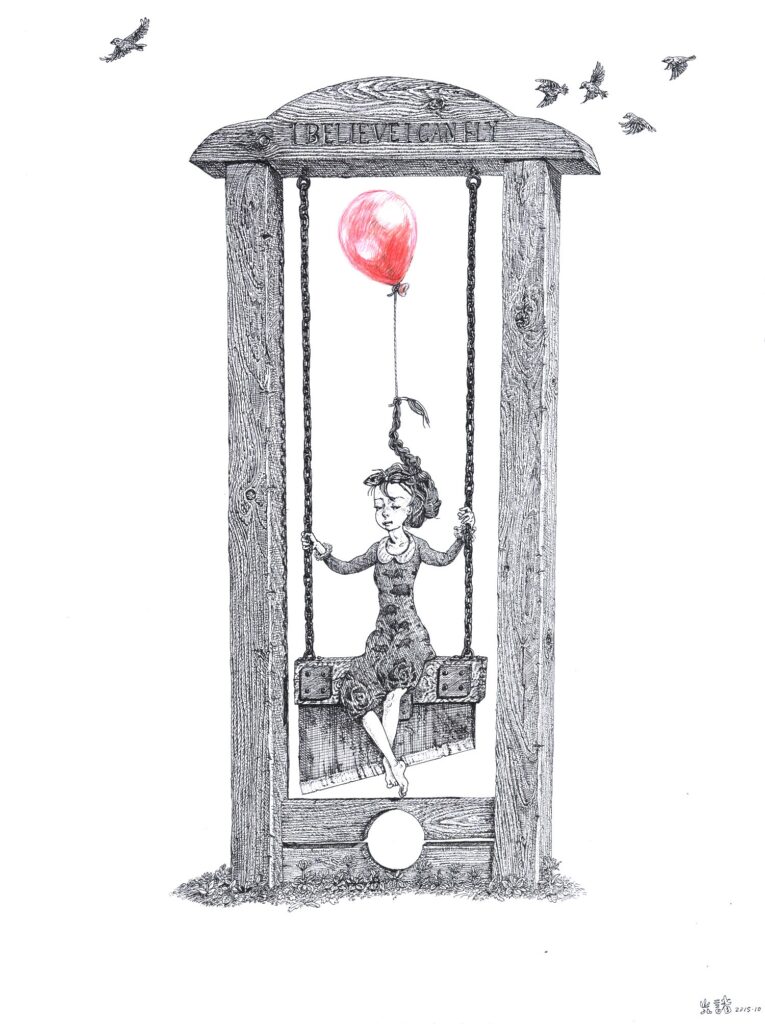

I first came across Kuang Chu by way of a red balloon floating into the corner of my eye, nestled among a few other art posts. The balloon was framed by a fantastical world that harkened back to the art of my own childhood – etched drawings featuring typography reminiscent of Alice in Wonderland and the detailed work of M.C. Escher.

Kuang Chu, having grown up in China and of a different generation, gave me a desire to explore the strength of art to act as a universal way to communicate.

In a bid to better understand his own creative process, how his past shaped his vision and the problems facing the artists in China today we reached out to Kuang Chu.

You can read our interview with him below…

Getting Acquainted

Please describe some memories from the stages of your life noted below:

* Age 5 beginnings:

I began to draw when I was very little. I can’t remember when.

And from the beginning, I knew I saw colors differently than other people. Kindergarten teachers always made a fuss when they saw I coloured the trunk of a tree with green, or painted ocean waves with purple. So I turned to black-and-white drawings.

I drew tirelessly.

Although China is a very poor country in the 1970s and 1980s, my parents could always manage to bring out enough paper from their government-owned companies.

In 1980, Man from Atlantis became the first American television series to be shown in the People’s Republic of China, which made a great impact on me. I was crazily drawing the fictional “underwater world” – submarines, corals, kelps, fishes, whales, sharks, octopuses, giant crabs…

Nobody taught me, so I must solve problems by myself.

My father tried to bring my drawings into some “Art Contests for Kids”, but soon found that my works, with its black-and-white setting, and “strange” theme (other children tended to draw something about “spring flowers” or “happy life in a Socialist state”), I was not qualified to enter a contest in the first place.

So it is fair to say from the very beginning, I was already an alternative artist. And I didn’t care much about the contest and whatnot – what was really important was I found out how to draw the twisting tentacles of an octopus!

* Age 10 continuations:

There are two separate and intertwined factors in my middle and late childhood: Shaped by my no-saying parents, and encounter with the horrible and sweet solitude.

It is well known that I create artworks in a deliberate and painstaking way. Maybe in a parallel universe, I could be an excellent doodle artist. I have the potential but it was severely hampered by my early experience.

I grew up in a family of perennial disapproval, and my parents are habitual no-sayer.

“Can I have a bicycle?” – “No.”

“Can I probe the abandoned bomb shelter with my friend?” – “No.”

“How do you think about my new drawing?” – “Not so good.”

Even after I grow up, my no-saying parents have always been sitting on my shoulders. So when I was doodling, if I did something familiar, there would a sound in my mind saying that I could do nothing novel; if I did something alien, it would be saying that this is rolling out of my handle, and I would do much worse in next stroke. This could drive me mad.

So it’s lucky for me that I don’t so dislike the deliberate and painstaking process of creation, and could draw gratification from the finished, solid, slick, and exquisite works.

I have no brothers or sisters, and my parents had all full-time jobs. So they often leave me at home by myself (it is legal in China at that time.) I must stay with myself for hours, I know loneliness at a very early age.

Curious enough, I found solitude is not so disagreeable. For me, it is even enjoyable. I read, drew, played with toys and all kinds of objects, imagined they are characters in a fictional world. I began to fall in love with solitude.

Only when I had to spend time with unfamiliar people, for example, when my father entrusted me to the care of my aunt for a short time, I would feel acute and painful loneliness.

In school, though not too outrageous, I was an odd and awkward boy. I had very few good friends, all of them are also odd boys. We did weird things together, such as digging holes in earth mounds at building sites.

* Age 15 getting serious:

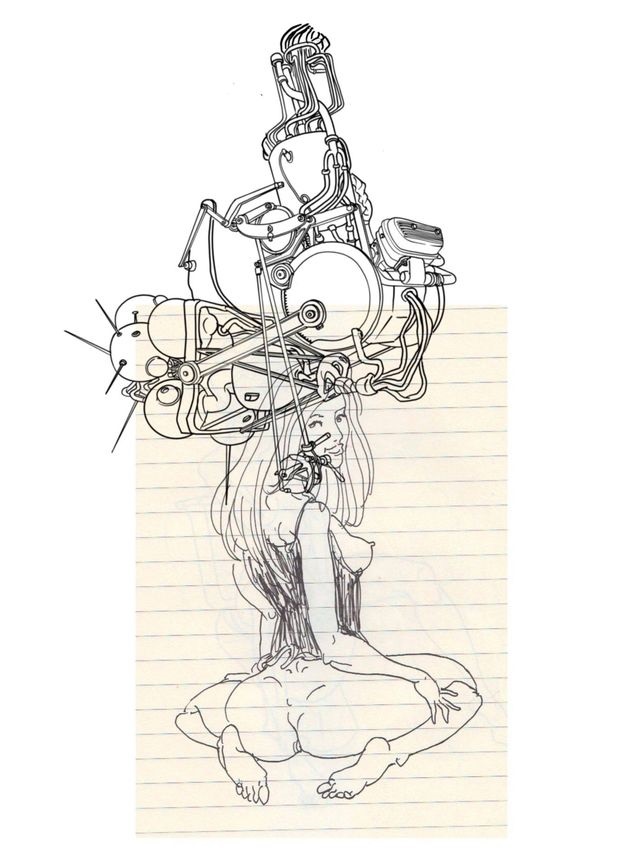

As a homely and nerdy boy, it is not surprising that my adolescence was far from impressive. When I was 16, I began to write poems and be interested in fine arts, notably modern art. Knew exactly I have deuteranopia (green-red color blind), which means I couldn’t study the two subjects I was interested in most ¬ art or biology ¬ in any school in China. So I compliant with the will of my parents, and studied at Beijing University of Technology.

I wanted to learn how to design cars, but because my score is not high enough, they only let me learn how to design armoured vehicles and tanks (that’s because at that time the salary in a car factory is much higher than that in a tank factory). And yes, I learned how to drive a tank.

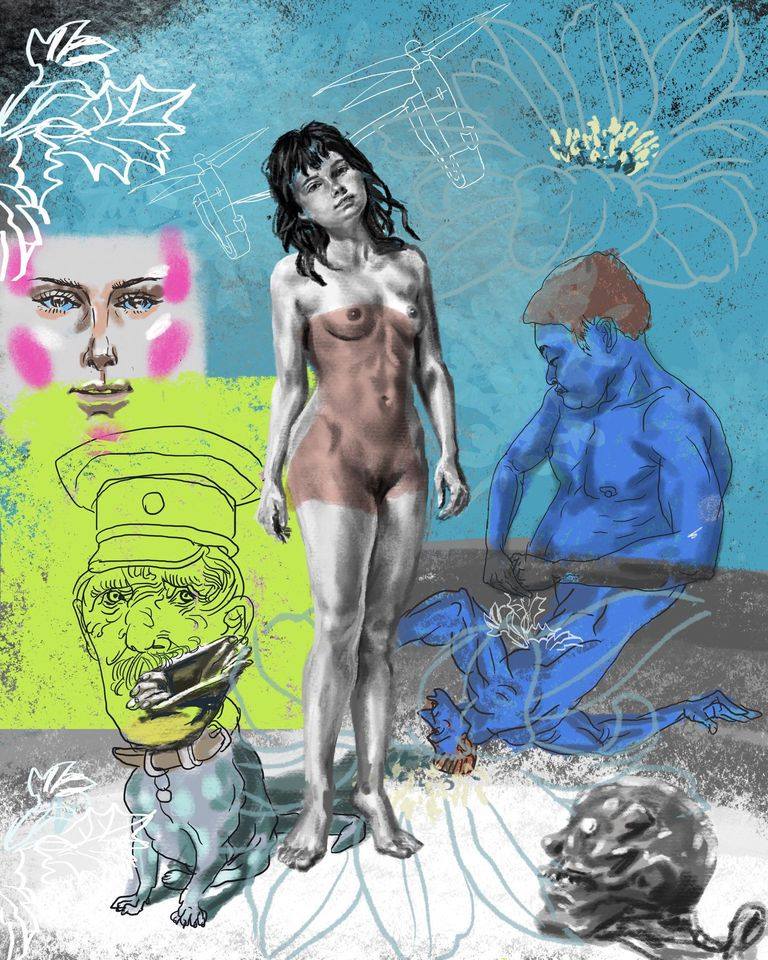

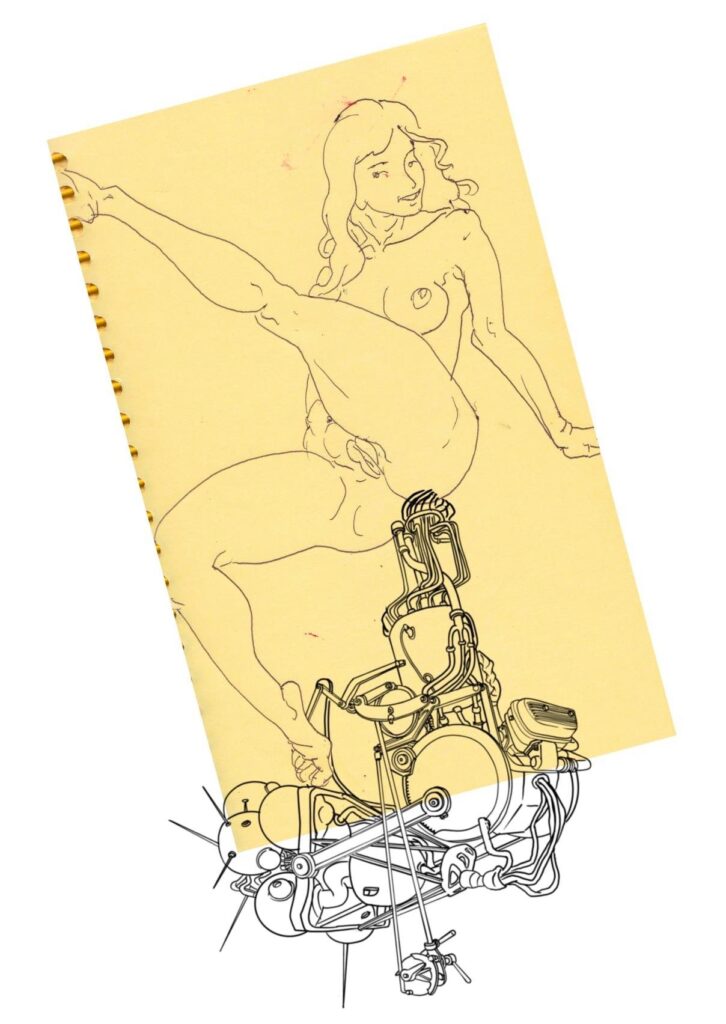

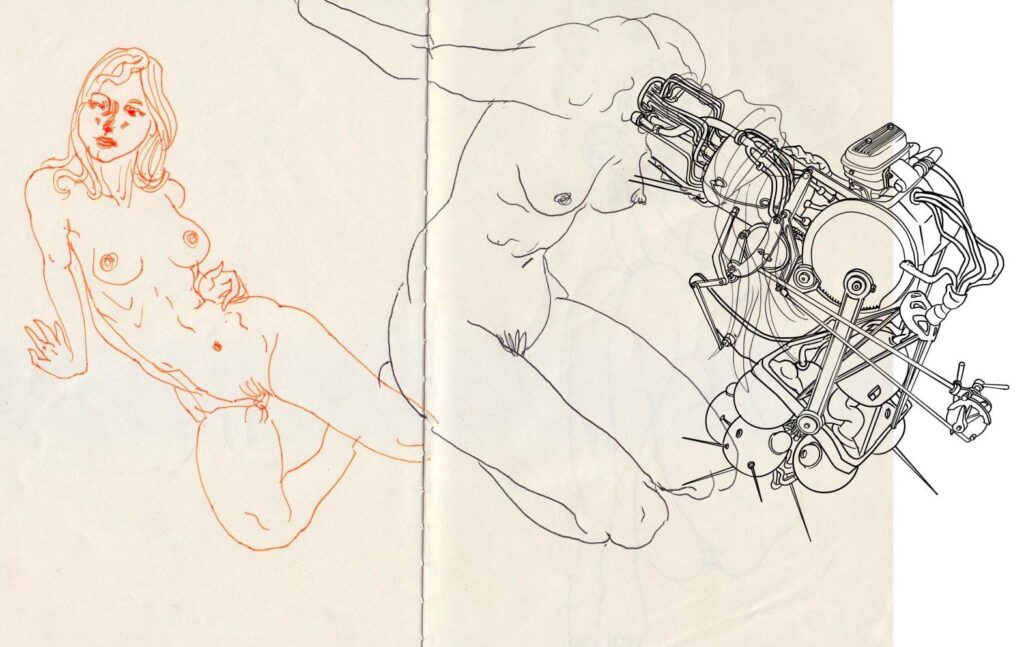

But the most notable event was I began to get the obsession with the female body.

At the end of the 1980s, some people began to try to make money in the less asceticism atmosphere in China. At that time, erotica was still strictly banned, but the publishers found a convenient bypass – they sell erotica with the tag “Nude Art”.

My first knowledge about a woman’s body is through looking at peddler’s “Nude Art” wall calendar. I remember clearly I found a big wall calendar at a street corner, on which there is a naked woman half-turned her back to the looker, in a angle that made her nipple almost visible. In quite a few days after school, I always made a detour to the street corner, close to the peddler’s tricycle, just to look at the wall calendar.

Still fresh in my memory is the smell of overripe fruits from adjacent fruit seller’s tricycles, and the solidly exciting electricity flowing in my body.

Today, my obsession with the female body is only stronger. Of course, I would not try to get too close to a woman’s body other than my wife’s, but I always feel thrilled by looking at beautiful women and girls, especially those wearing fewer clothes.

And in a hindsight, I found by looking at the “Nude Art” calendar, I at the first time knew the feeling of enjoying and creating true art – solidly exciting electricity flowing in my body.

* Age 20 young adult:

For the first time had a girlfriend, marveled at a real girl’s naked body.

Graduated from Beijing University of Technology. Worked as a worker and then an engineer in a Jeep factory (because my mother was a senior engineer working in that factory).

Took a GRE test, learned a lot of Englished words. But didn’t apply to a college in the USA.

Quitted the job in the Jeep factory, and began to work as a reporter in media.

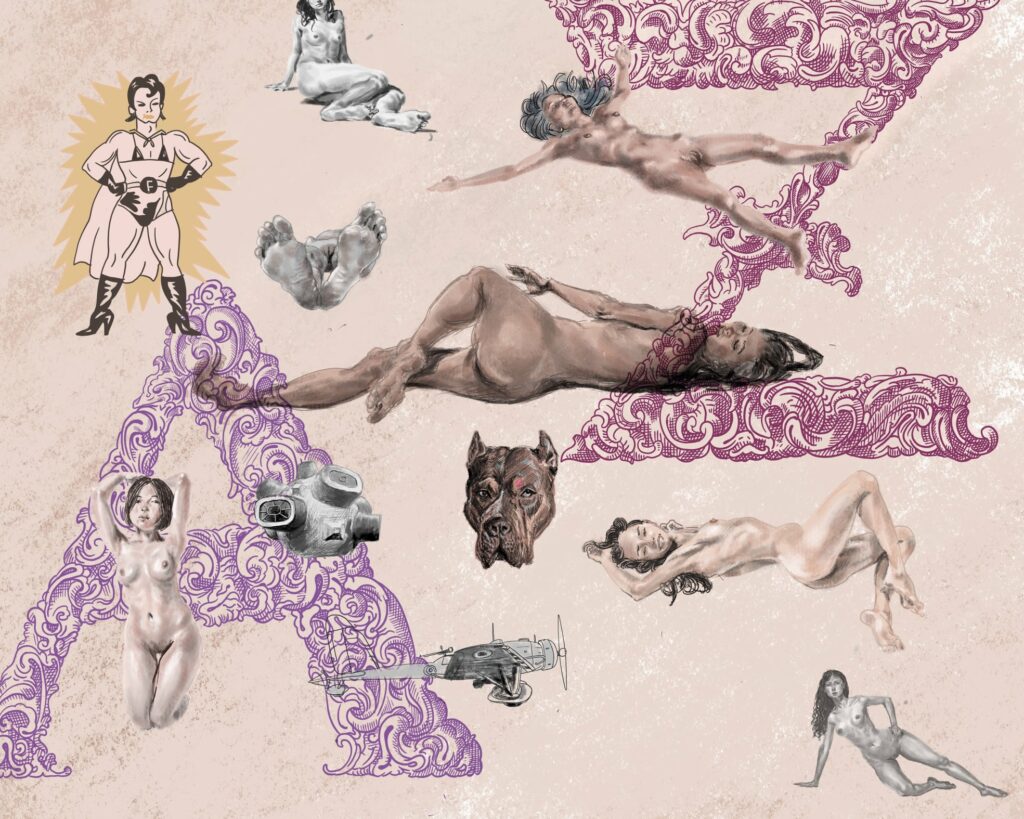

Monkeying as a half-hearted amateur visual artist.

Wrestling with my over-protect and control-freak parents.

The complicated love-and-hate emotion had become an entrenched theme of my creation since then.

The most notable happening in my 20s was starting to find beauty and quaintness in solo travel. I travelled to many mundane places in China by myself, and found there is not such a thing as an “uninteresting place” in the world.

At the same period, I fell in love with Elizabeth Bishop‘s poems and decided that my artworks, whatever it would be, should be like Bishop’s poetry: a tapestry of beauty and quaintness, mundane and surprise, irony and sympathy.

* Age 30 fully formed:

Start a disastrous marriage.

Wrestling with my over-protective, disapproving, and control-freak parents.

Working in media as a slacker.

Monkeying as a half-hearted amateur visual artist.

* Age 35 meanderings:

Working in media as a slacker.

Monkeying as a half-hearted amateur visual artist.

Failed to be a caricaturist.

Failed to be a columnist.

Failed to be a cartoonist

Failed to be a novelist.

Failed to be a scriptwriter.

Wrestling with my over-protective, disapproving, and control-freak parents who were more and more assured that their disapproval was right.

At the end of my 30s, I eventually divorced my first wife, quitted all my jobs, and started to train myself as a professional visual artist full heartily.

* Age 40 adult meanderings:

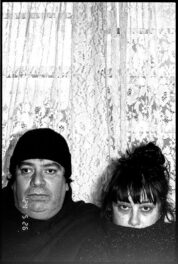

Got married to my second wife Tia Xia.

Everything began to go well.

Started to create the “Red Balloon” series.

Started to read English books.

Published three books in English: “Magic of Lines”, “Magic of Lines II”, “The Dark Book”.

Travelled to Australia two times.

* Age 45 middle age approaches:

Took part in an artist-in-residence program in Poughkeepsie, NY, The USA.

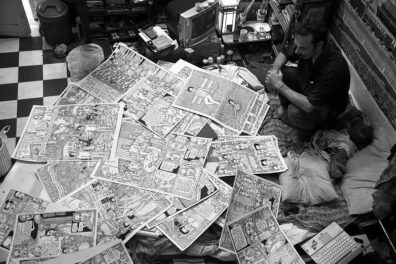

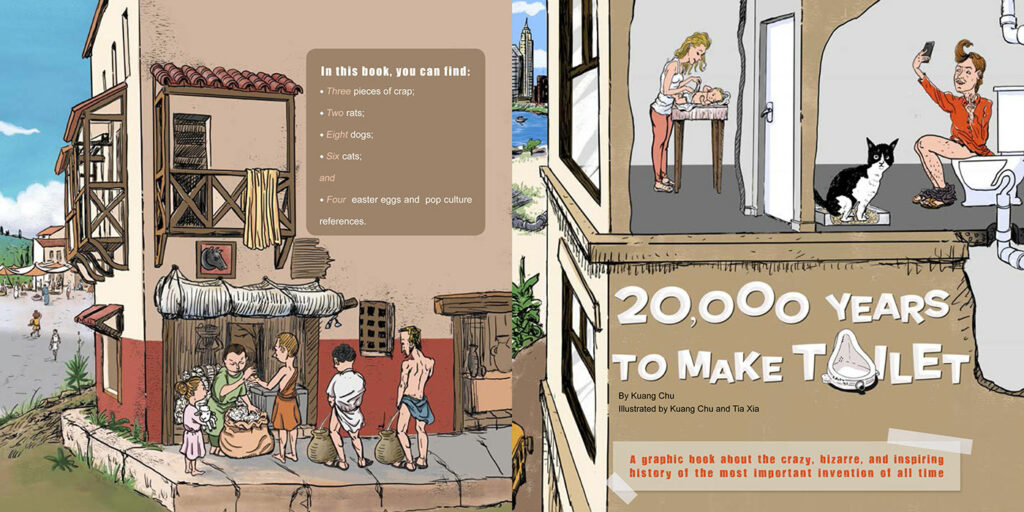

Wrote and drew a children’s popular science graphic book “20,000 years to make toilets” with my wife Tia Xia, which is still selling very well in China at the time of writing.

Started to use iPad Pro and Apple Pencil to draw this batch of the “Red Balloon” series.

Held my first solo exhibition “Red Balloon: Spirit Visible” in Shang Hai.

People began to notice me, including The Aither.

Personal motto(s)?

Just finish what you’ve started.

When and why did you first start to make art?

To answer this question, I shall first tell you how do I define the term “art”:

I think “art” is something a person believes he/she shall do, no matter if it is needed, understood, or accepted by other people, and no matter what or how long it takes.

According to this definition, I only began to make art in 2019, when I used iPad Pro and Apple Pencil to draw this batch of the “Red Balloon” series. I knew “it is that” from my gut, and I will do it for a very long time.

But the idea and confidence of making the “Red Balloon” with that approach didn’t come up out of blue. I had walked a long way to find myself and the art I shall make (and I think they are virtually the same thing).

I began to draw when I was very little, and I had made many artworks that I want to bury forever, they are skeletons in my cupboard. I prefer to tell everybody I started to make drawings in 2011 after I quitted all my jobs. But the truth is, I kept trying to make art from 4 to 46, and at the age of 46, I began to make art.

…and any pivotal artistic moment(s) / influence(s)?

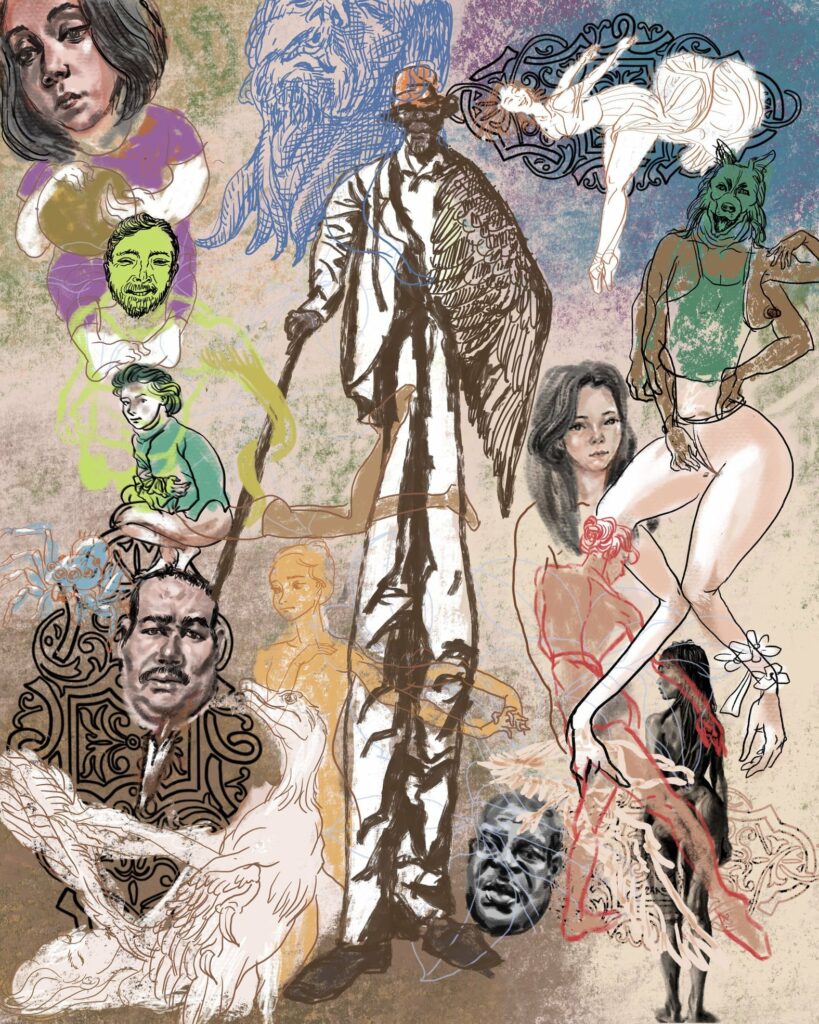

The pivotal moment is the emergence of the Internet in the 1990s, and the tour in Australia and the USA in the 2010s. These opened my eyes, let me know there are so many “strange” arts in this big world. I decided to find my own “strange” way to make art.

Please describe the usual process involved with producing your various art from initial idea, to creation and finish?

Two pivotal factors define my life so far:

One is I have symptoms of Attention Deficit Disorder, so I can’t do anything that needs hours of immersion.

The other is I also suffer constipation, and I can only make art when I have relieved myself properly.

Yes, I do live fully, read a lot, make food by myself, walk two hours and recite three new words every day, but the time I can really used to make art is relatively short and intermittent. Paradoxically, the combination of these two factors makes me only fit to make very time-consuming arts, because I can finish them bit by bit over a long time.

I have never been lacking ideas since I was young, but I can only do things slowly and methodically, rather than emotionally and improvised. When an idea flashes in my mind, I will catch it, evaluate it, if it is worth to be materialized, I will remember it and add it to the task list.

When I begin to draw, I usually find that what I’ve done, what I could do, and what I think about the image at first – are three different things. I will think about that when I’m in bed.

The next day I maybe continue to draw based on what I have done, or re-do it in a different way.

The image I eventually created is always not the same as I have supposed them to be, but it has its own merits.

Favorite other artist(s)?

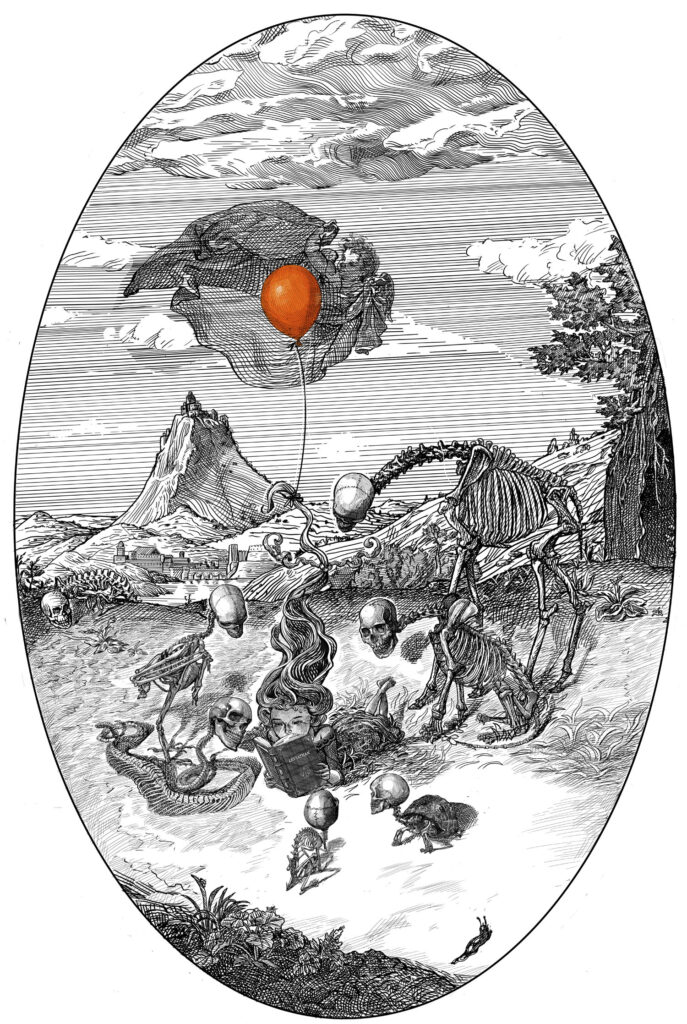

The type of artist I think I should be: M.C. Escher.

He is also a printmaker. He can’t be shoehorned into art history, but he also can’t be erased from the history of arts.

My techniques are from: Albrecht Dürer, Athanasius Kircher, Hendrick Goltzius and Gustave Dor.

Contemporary artists that I’m emulating: James Jean, Gary Baseman, Ray Caesar, Mark Ryden, and Audrey Kawasaki.

Any projects you want to hype?

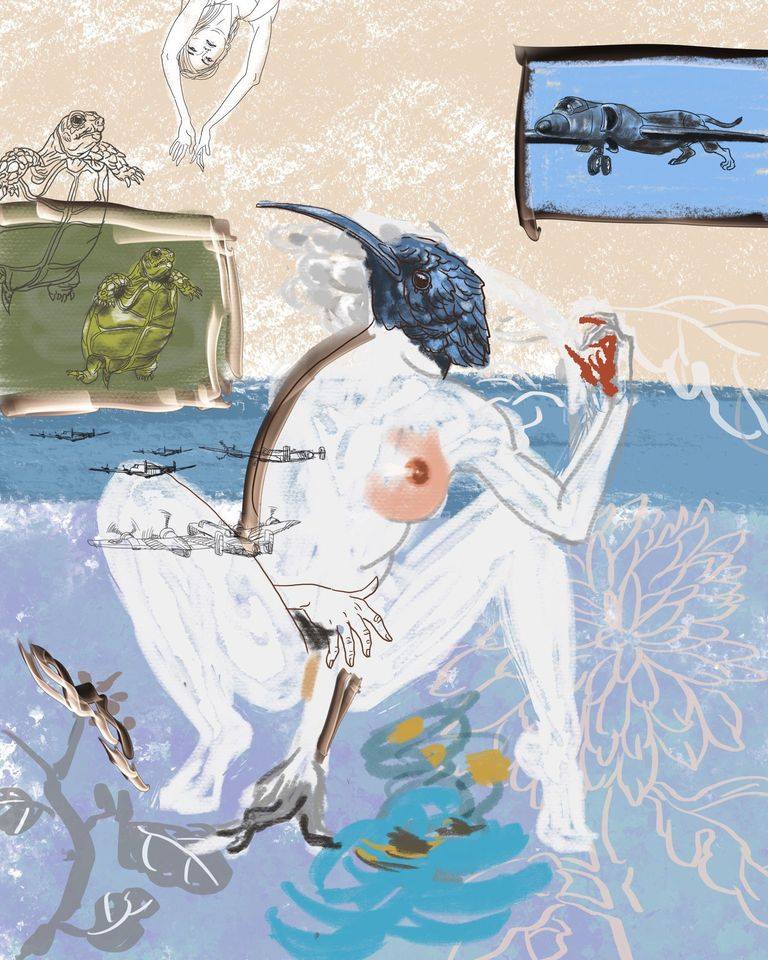

In the foreseeable future, I will continue creating the “Red Balloon” series. I have so many good ideas waiting to be made into images. And I’m scheming to publish an album of the “Red Balloon” series.

To enrich the contents of that book, I will cooperate with brilliant novelist Pupil Black, who will write a short story for each installation in the “Red Balloon” series. So the book supposed would be like some kind of graphic novel, in which both pics and novel are all souped-up.

If we are lucky, we will see this book in two years. Please keep your fingers crossed.

If people wanted to work with you, have a chat or buy something ¨C how should they get in touch?

My Email: ghostinthezoo@foxmail.com (Ghost in the zoo, isn’t it cool?)

My Facebook: Kuang Chu (https://www.facebook.com/kuang.chu.7564/, find me here please, I’m chatty and funny.)

My Instagram: kuangchu.art (I don’t like Instagram very much, so I just treat it coldly as a portfolio of my artworks.)

(Photos by Liu Di from the Red Balloon Photo Series.)

Odds and Ends

What is your earliest memory of art or a book that influenced your interest in typography?

When I was a Child, China was a very undeveloped country. So there were very few color pics printed on coated glossy paper for a child to look at. That’s why I was so impressed by the black-and-white illustrations in books such as “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, “The Wizard of Oz” and “Charlotte’s Web” (they are all in Chinese edition, of course). These pics kindled my aspiration to create images.

I didn’t see, at least didn’t notice any good paintings or sculptures in the whole childhood, so when I grew up and embark on a career as an artist, it is natural for me to chose black-and-white drawing as my main approach to making art. Red-green color blindness is another reason, but I don’t think it is the most important one.

Soon after I began to create black-and-white drawings, I found that there were so many highly talented people doing the same thing, and what they did is much better than me. So I must find a unique way to make me be distinguished.

In 2014, I found everything about the old European engravings fell into place for me creatively.

Firstly, it is very satisfying for my needs for neat and traceable lines.

Secondly, I like the technique some engraving artists such as Hendrick Goltzius and Gustave Dor were good at – using tapering lines as a device of shading, which is using the thick part to make the dark side of an object, while the thin part the bright side.

Lastly, the look of old European engravings conjures up the spirit of the Renaissance and Age of Discovery – the curiosity toward the vast unknown in the world, which is the same vibe I think my own works should have.

Can you explain the significance of the Red Balloon in your current project, what does it represent to you?

The image of the Red Balloon came into my artworks was by sheer accident. The first entry of the Red Balloon series, ‘The Well’, is based on an image that appeared in my head for no reason. That was like a screenshot of a mystery/crime movie: a girl standing at the edge of a well, looking into its dark inside, a red balloon tied on her braid, floating in the air.

Soon I decided to adopt the red balloon as a common feature for a series of drawings.

Bright and always rising, the balloon is confronting, at the same time balancing the darkness and depression of the surroundings. Although I don’t like a single and concrete interpretation of an artwork, one would not be wrong in saying that the red balloon is a symbol of hope, or a materialization of high spirit.

Your work feels like it varies between fantasy with whimsical creations and realism in exploring the female form, what inspires you to explore contrasting styles as an artist?

That’s because my works are not orthodox Surrealism, such as the splendid printworks made by Max Ernst. Every work in the Red Balloon series is about a normal girl walking into some strange environments unwillingly, and telling about a section of her story.

In most adventure stories, the protagonist shall be normal, though the environment he/she is in can be as grotesque as possible. Say, Alice could be heroin of the “Adventure in Wonderland”, but Queen of Hearts could not. So, in my works, there is a contrast between a fantasy environment and a realistic female form.

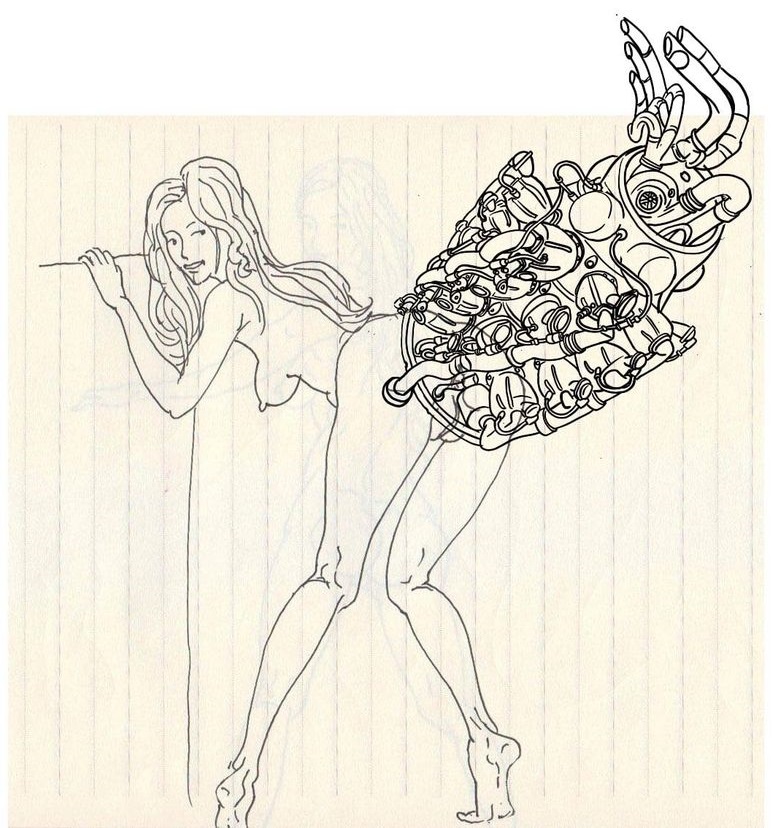

At this point, we must talk about another topic: I’m a hybrid of a visual artist and a story-teller. For a very long time, I was torn between being a man of letters or a visual artist.

I used to work as a reporter, popular science columnist, and screenwriter, who loved drawing and tried to be better than other amateur artists. Eventually, as fate would have it, I became a visual artist, although not one in the pure sense. I tend to initiate and construct an image with spoken language rather than pure visual messages. So most of my works begin with a scene from a story: A girl is facing a mysterious well; a girl is in desperate love with a giant beetle; a girl is on the back of a giant caterpillar fighting a giant black bird, etc.

Can you talk about your experience in commercial work, such as “children’s popular science”, both challenges and rewards?

When I was a child, I was a quintessence target reader of magazines such as “National Geographic Kids” or “Ask Magazine by Cricket Media”. When I was in my 20s and 30s, my favorite books are about popular science. And the last job before I quit all my jobs is working as a popular science reporter for Beijing News, one of the most prestigious newspapers in China.

Popular Science is a rather marginal department in almost every newspaper, but that’s exactly what I wanted. I can work more easily and under the radar of my boss, so I can spend more time making my artworks.

All in all, I am both nerdy and have a knack for conveying ideas to other people, a golden combination for a popular science writer. So it is not surprising that a publisher in China asked me to write and draw a children’s popular science graphic book about the history of toilets named “20,000 Years to Make Toilet.” I finished collecting materials, writing and drawing the linework, and my wife Tia Xia did the coloring.

I think there are less than ten people who can do both writing and drawing works of a popular science graphic book, I am one of them.

Tia and I finished that book in less than five months, it was very hard-pressed. Sometimes I felt my neck had been broken, and I was going to drop dead. If I have one year to do the work, “20,000 Years to Make Toilet” would be way better than it is now.

Although I’m so good at making children’s popular science books, and it is really profitable, I’d rather make fine arts. On the one hand, I feel fine arts are of greater value, and on the other hand, I don’t like to debrief about my ideas and progresses, and hate to change my work according to other’s opinions. So, I would feel more comfortable if I can finish a work only by myself

What role did toys play in your upbringing?

When I was little, there were not many toys to speak of. Just as I have said, China then was not very unlike today’s North Korea. I had a tin locomotive, a tin plane, a tin handgun, a tin chicken, a tin frog, and a wood car. The tin plane was driven by a friction motor, the handgun had a flywheel inside, the chicken and frog were driven by wind-up machines, while the locomotive and car could only be moved by hand.

That’s all.

I had not much experience with toys to speak of in my childhood. Most of the time, I was “play” with animals. But I had not dog and cat to play with, so I always played with coldblooded animals, such as insects, snails, worms, and fishes. But from hindsight, I found that “play” is a too flattering word for what I’ve done, a more precise word shall be “harass” or “torture”.

I tortured and murdered too many lives when I was a kid, so I think the extreme misfortune I suffered before the age of 40 was not for no reason.

So, the toys, or lack thereof, played a pivotal role in my life. That made me very familiar with animals. When I was puerile, I was familiar with their wriggling and disintegrating; when I was more mature, I learned to respect them, and admire their beauty and frequent quaintness. One can easily find these in my artworks.

What are the top 3 items you own?

I’ve never few very happy before I was 40, so I’ve never felt the older time is better. So I would not deliberately keep anything from the past.

And I hold a belief that an artist (at least of my type) should live a life as spartan as possible, so I think material possessions are rather a curse than a blessing.

So now I can answer this question: My memory, my memory, and my memory.

What are the major challenges artists face in contemporary China?

First of all, the lack of freedom. As an artist, I think visual arts should be given freedom as much as possible. Do arts that are politically incorrect, pornographic, or gory are harmful to the society? Maybe, maybe not.

I am not God, and the only thing I know is God told me to be free when I’m creating. And I don’t think there is a place in the world where artists have total freedom of creation, but the lack of it in China is exceptional.

If the degree of creative freedom is a ladder, China is on the lowest rungs, only higher than a handful of countries, such as North Korea, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. As for China’s visual arts, outspoken political comments are strictly prohibited, the tolerance towards sexuality, goriness, and violence is very low.

Above is only the external layer of that topic. It is true most artworks that a Chinese artist wants to create are not political, gory, or overtly erotic, at least most installations in my Red Balloon series are not.

For most visual artists in China, the possibility of coming across censorship is relatively low, but the fear of censorship itself could also be detrimental. The fear is like cold foul water, infiltrating into each and every brain cell of a Chinese artist, killing his/her imagination, constraining his/her boundary, and making his/her hands move abnormally. That’s why so many Chinese artist’s works give out an air derivative, lackluster and dry.

There is a great analogy to help explain this phenomenon: almost everyone can walk with ease at a beam placed on the ground, but if that beam is elevated to be placed on the top of two one-hundred meters column, then very few people would manage to walk on it, and quite a few of them would fall, even if there is no wind.

That’s the fear itself that makes people fall.

Secondly, although China has been the second most “badass” country, it is still a developing country. In many aspects, China still lags behind the Western countries, and the Art Market is one of them. It is true that quite a few Chinese had become hotshots in the international art market, such as Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo Qiang, Xu Bing, and Fang Lijun, but all of them are little known, appreciated, let along collected by ordinary people in China.

When it comes to the middle-market, where people in my neighborhood could buy original artworks, there is very little to speak of. As far as I’ve observed, Chinese people generally know very little about art, they never think of collecting artworks, if they want to buy artworks to decorate their rooms, they normally consider traditional Chinese wash paintings, run-of-the-mill landscape painting, or a cheap copy of Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies”.

So, where is the place for an artist like me? I’m not a top-notch international artist, nor a “decent” traditional painter, most people in China don’t understand what I’m doing.

“Are you making black-and-white drawings?” (In China, black-and-white drawing is considered as art school students’ practice.)

“Why shall I buy your drawing?”

“Are you making illustrations? Why shall I buy your illustration?”

“Are you selling prints? But I want to buy a ‘real’ artwork…”

I feel I am living in limbo. I believe that many other artists living in China share the same feeling.

Thirdly, many Chinese artists must be wrestling with the rage against the political system of China. Below is my own story, I believe it is typical in China.

I used to be a “Red Child”, loved the Chinese Communist Party by heart. In 1989, as a middle school student living in Beijing, I saw the great protests that occurred in Tiananmen Square, and heard about the crackdown and massacre on June 4, my belief began to waver.

From then on, I knew more and more about how many absurdities and atrocities have been done by the Party, how senseless and out of date is the political system of China, and what a catastrophic future we will face if we don’t make a change. But I also knew better and better how brutal the party would treat you if you are outspoken. So by age 40, I became a Chinese dissident, who had never said an audible dissident word.

Somebody may say it is reasonable and acceptable that there are different type of political systems coexist in the world, so a one-party state is nothing wrong. Even if that is true, one can also easily find apparent absurdity in China’s system. The forever-ruling party in China names the “Communist Party”, but is China still a Communist state? Definitely not!

Now, on the one hand, the party lets the capitalists exploit the workers to the extreme, on the other hand, it rules China with blatant rhetoric of Nationalism. Then why doesn’t it change its name to “Nationalist Party”? Why does a party that doesn’t believe in Communism anymore still call itself “Communist Party”?

If the ruling party tells barefaced lies every day, how could the people of that state preserve their integrity?!

I know many friends from English-speaking countries also feel disappointed with their own countries’ political systems, but believe me, what happening in China is a different thing. There is no paradise on the ground, thus no perfect government at any moment. No policy could please everybody, but the people in English-speaking countries have ballot tickets, could embark on a street protest, have a speech in Hyde Park, and public books written by themselves at will.

The whole society may trek through the bog of dissatisfaction and impossibility, and reach a state that is a little more beneficial to everybody. If that was not feasible, the society at least could sway between “Left” and “Right”, Conservative and Liberal, Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism, nobody would be unhappy forever.

But in China, you just could not do, or dare not to do anything. It is just like you are on board a slave ship, seeing the atrocity done by the slave trader, and knowing it is on the course to hit an iceberg, but you can just do nothing. You are in a rage caused by your incapability of emancipating the slaves, as well as saving the whole ship.

Of everything you have done what would you most like to be remembered for and why?

I hope the Red Balloon series, finished and yet to create, stands the test of time. That doesn’t mean Kuang Chu would be a household name, that is just impossible – even Hendrick Goltzius didn’t make it. What I want is 100 years later, the images I created could be seen (I’d more like to say “float up”) on pages of Pinterest (if at that time Pinterest still exists).

And the single thing I think I shall remember forever is met with my second and current wife, Tia Xia. At the beginning of 2014, I met her in Beijing, and on the same day we decided to spend the rest of our lives together.

Tia is also a remarkable artist, you can check her out on Facebook and Instagram.

Links

- Kuang Chu – Instagram

- Kuang Chu – Facebook

- Kuang Chu – Behance

- Kuang Chu + Tia Xia – ‘20,000 Years to Make Toilet’ Book – Via Behance

- Tia Xia – Instagram

- Tia Xia – Facebook

- Tia Xia – Behance