He is not a cigarette smoking Minotaur; nor is he the traveling Despondent Man. But without Steven Sherrill, a self-proclaimed “devout imperfectionist,” neither would exist.

Both are Stevens’ creations: not mere mobile art projects, not just life-size human replicas, but doppelgangers and paradox.

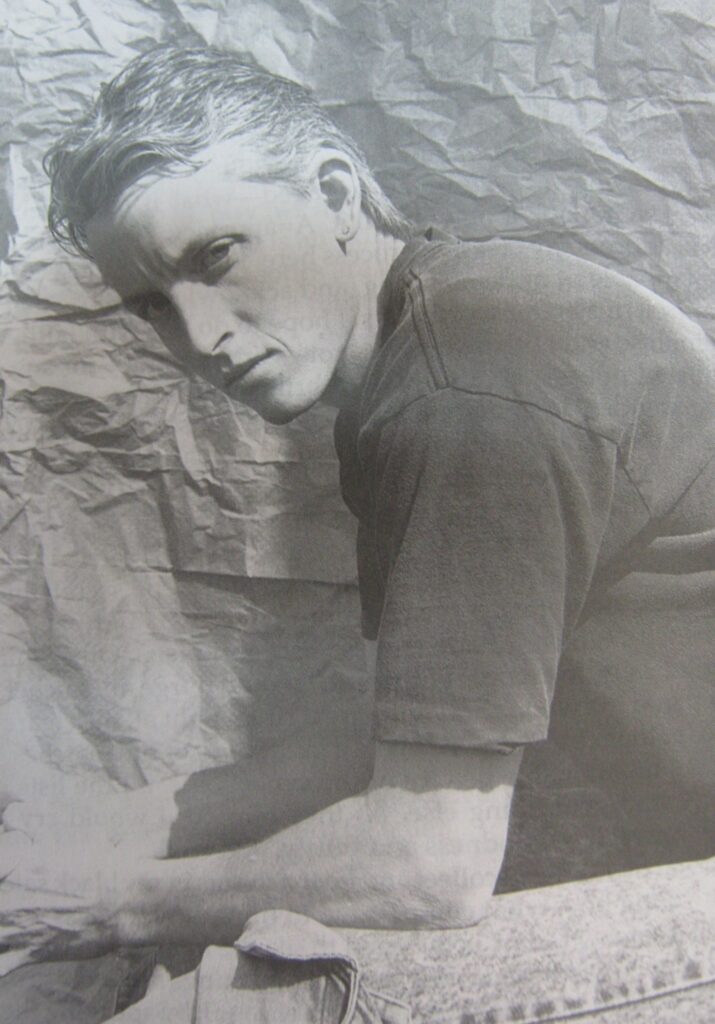

Novelist, poet, painter, sculptor, photographer, musician – Steven Sherrill is a one-man creative chain-gang, swinging the sledge hammer of obsession.

He will not say whether or not he, like the aforementioned Minotaur, has horns; but Steven has been using words to disturb the peace since 8th grade. When he was suspended from school for writing a disturbing story – Title and content now lost to memory.

He also refuses to divulge the contents of the Despondent Man’s mythical valise; in fact, he’s insistent that he does not know what’s inside this battered bit of luggage he carries wherever he appears.

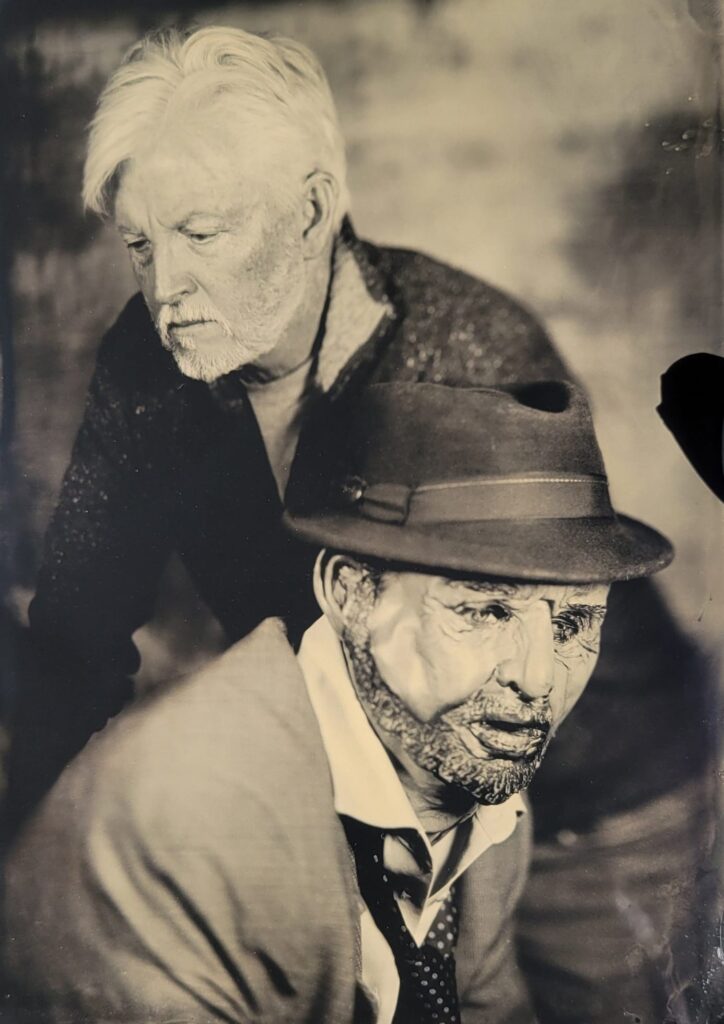

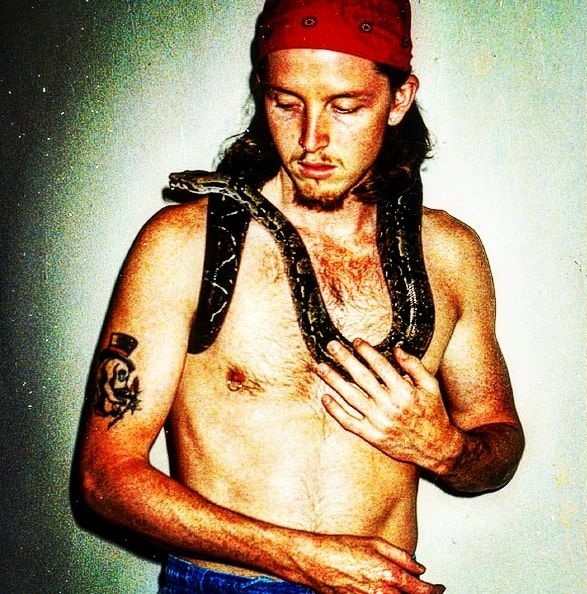

Along with a photo of Steven with his creation.

Born in 1961, Steven spent his early years in his native North Carolina. He dropped out of school in the 10th grade, and ricocheted around the southern US for years.

He eventually earned a community college Welding Diploma, which led circuitously to shelves loaded with his strange, disturbing, raw-edged fiction.

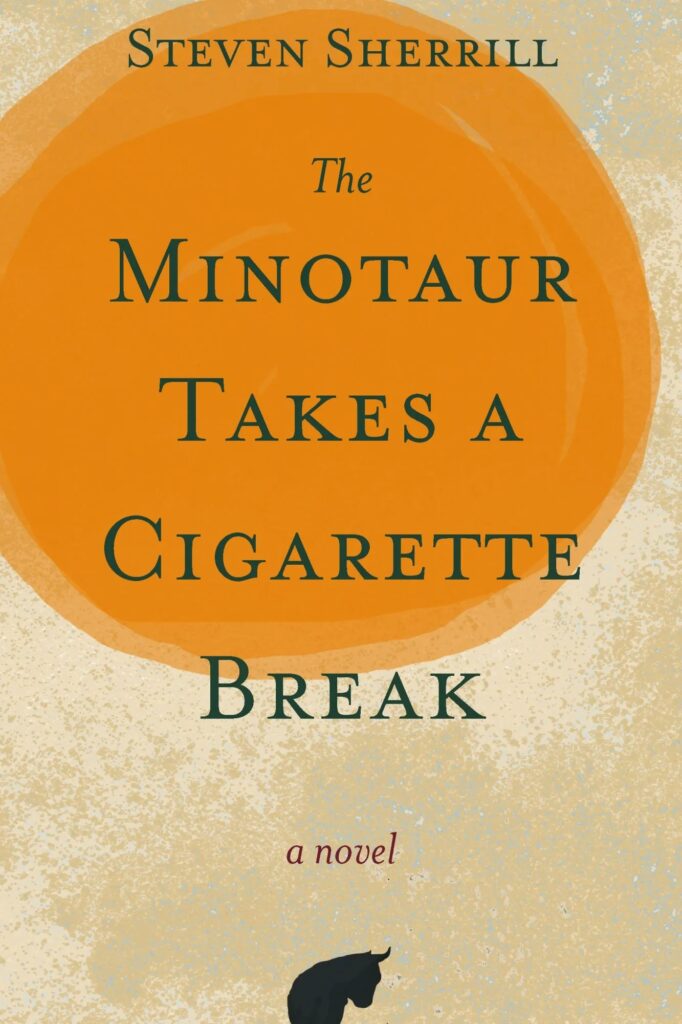

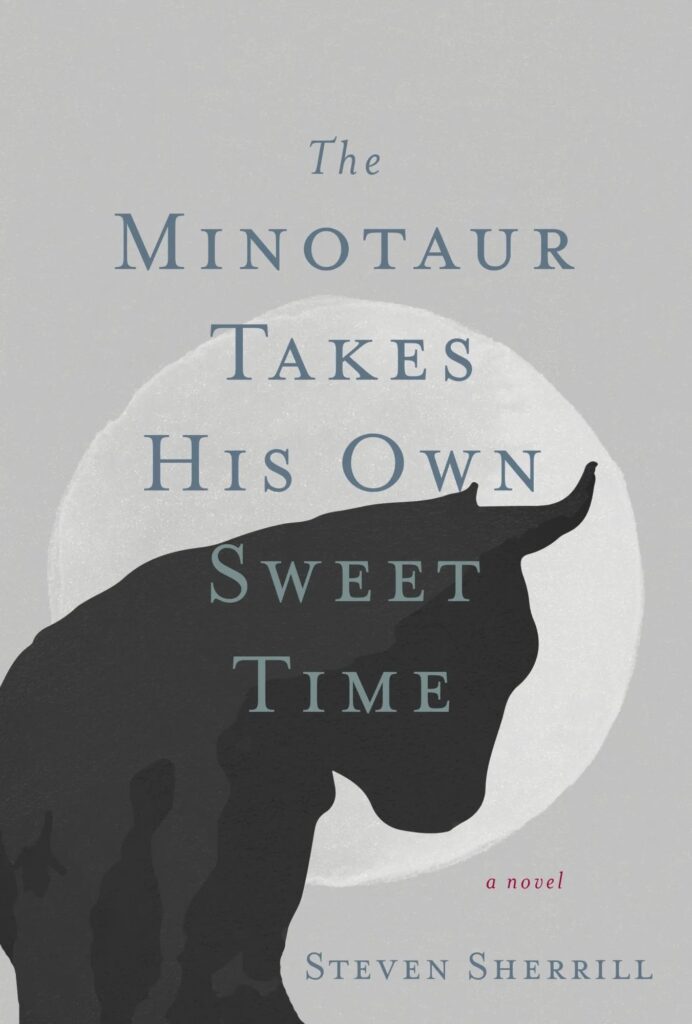

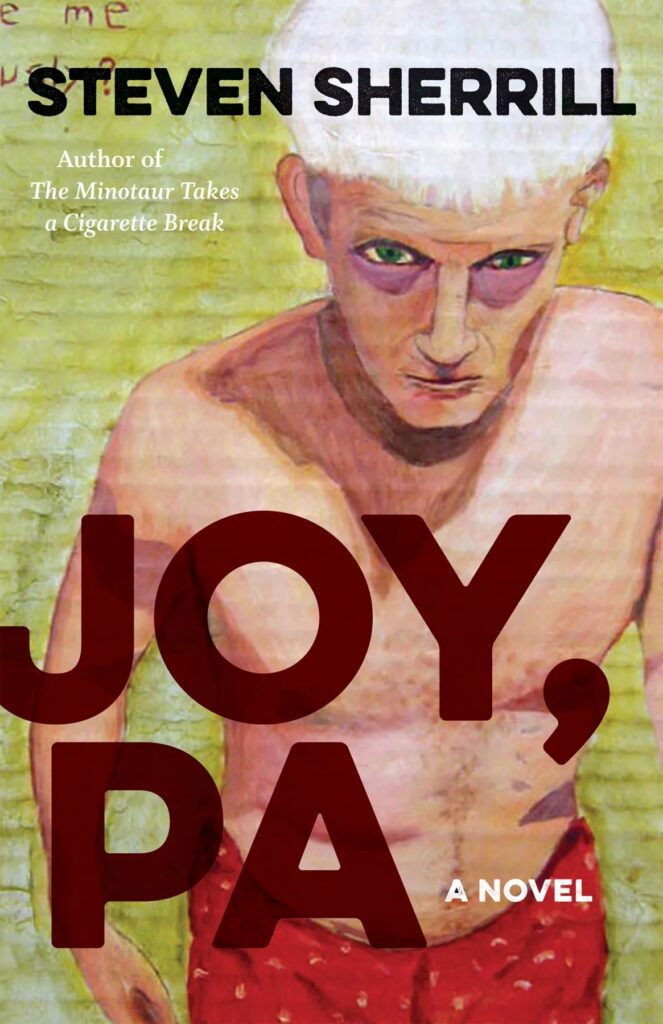

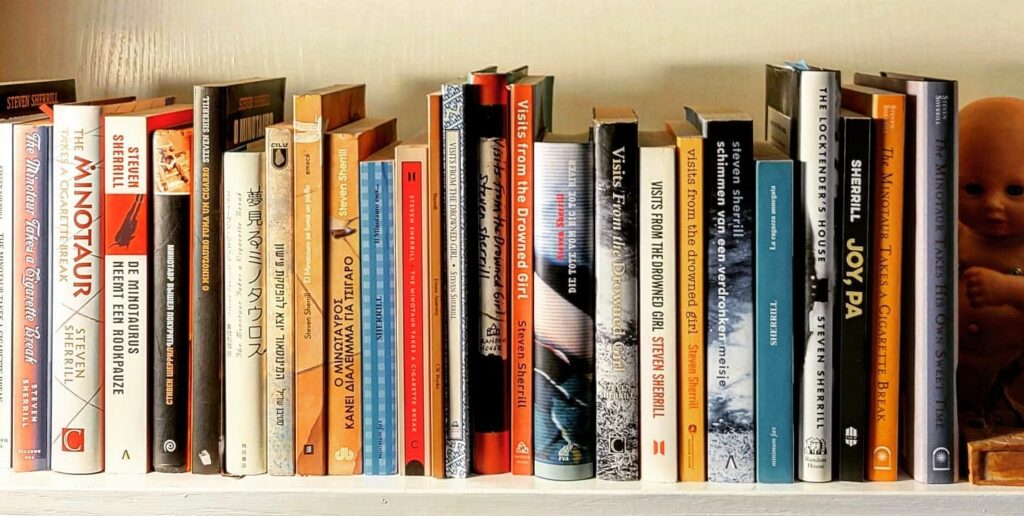

Probably best known for his novel, ‘The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break’ – released in 2000 and translated thus far into seven languages – he has published nearly a dozen other books, each of them probing the depths of isolation, outsider fascinations, and otherness.

First published in 2000.

I met Steven in the aftermath of a big all-day Sacred Harp sing – That is, a hundred people singing four-part harmony, loud as hell, for six hours.

As the sun was going down, half the singers ended up at a house up on a hill, at the end of a very steep dirt road.

With banjos frailing and fiddles scratching out old mountain tunes in the next room, with little knots of insatiable singers going at it again, Steven and I huddled to talk about the writing life.

I was deep into research on my then-current project (‘Flaherty’s Wake: Abortionist, Lawyer, Boxer, and Priest’) and Steven was adamant that I had to finish the book, though I was struggling to make sense of all the evidence I’d gathered.

He too was in mid-stream, though he doesn’t like to discuss a book until it’s done.

We talked about sea chanteys and I ended up attending some of the gatherings he later organized, to add my voice to the raucous nautical din.

I also learned that his creative energies didn’t just flow into the written word and the shouted song…

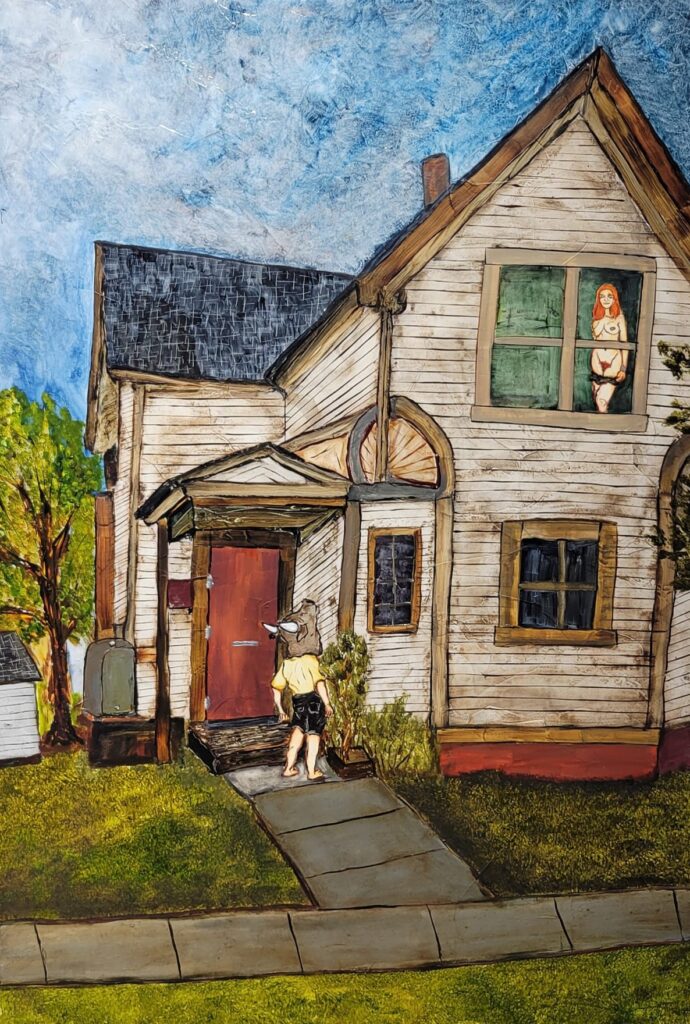

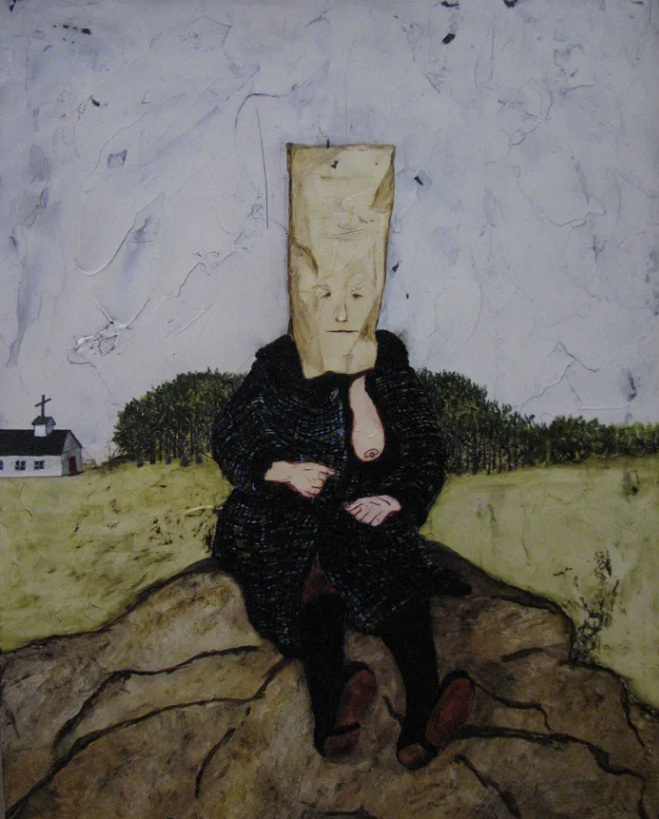

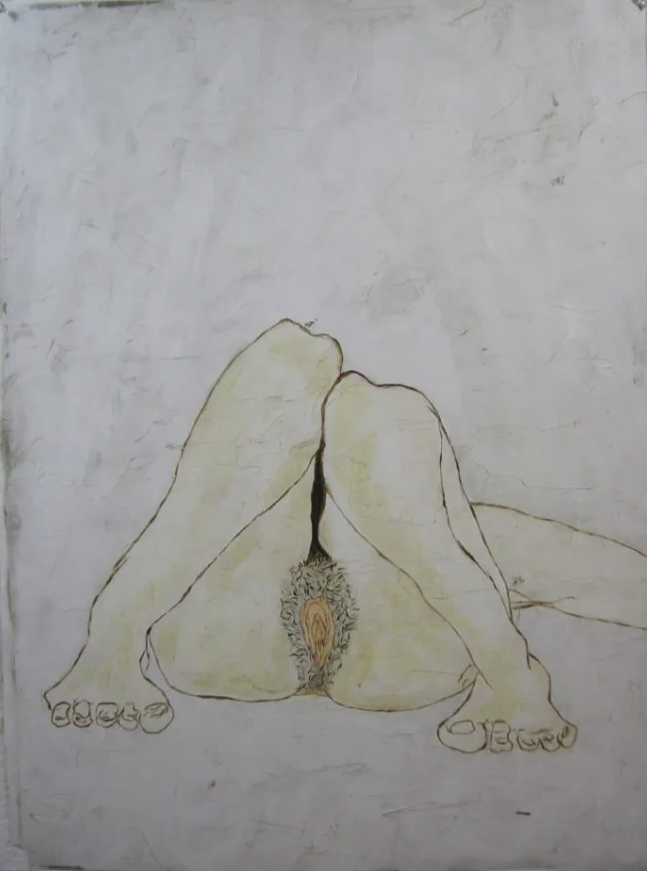

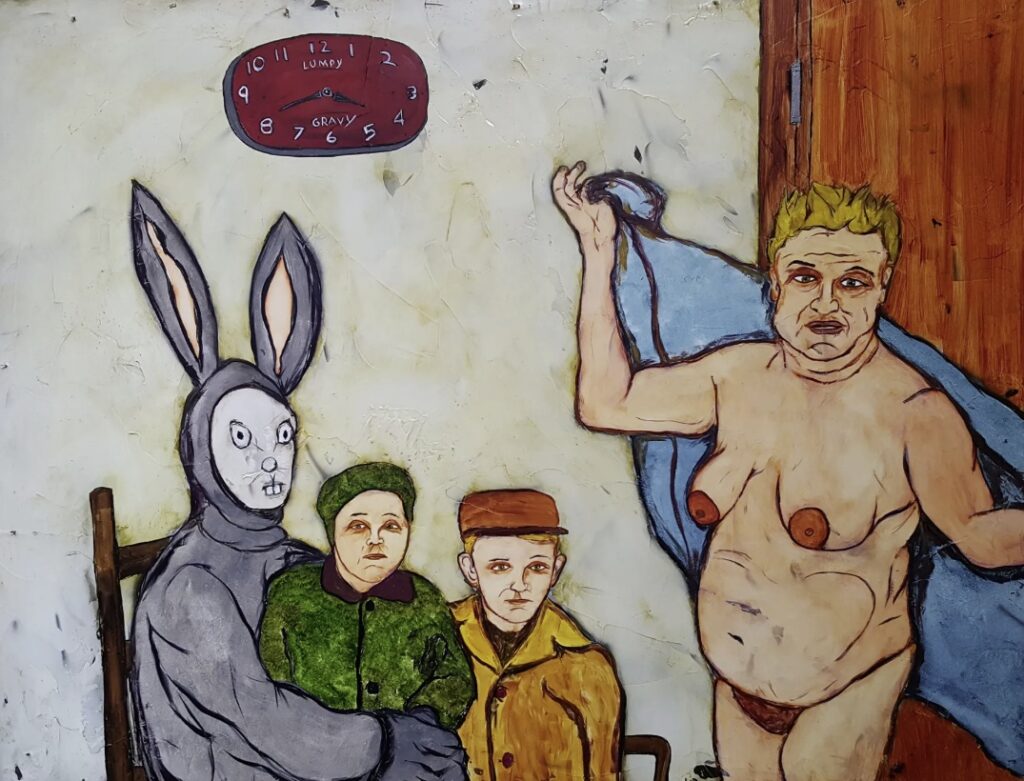

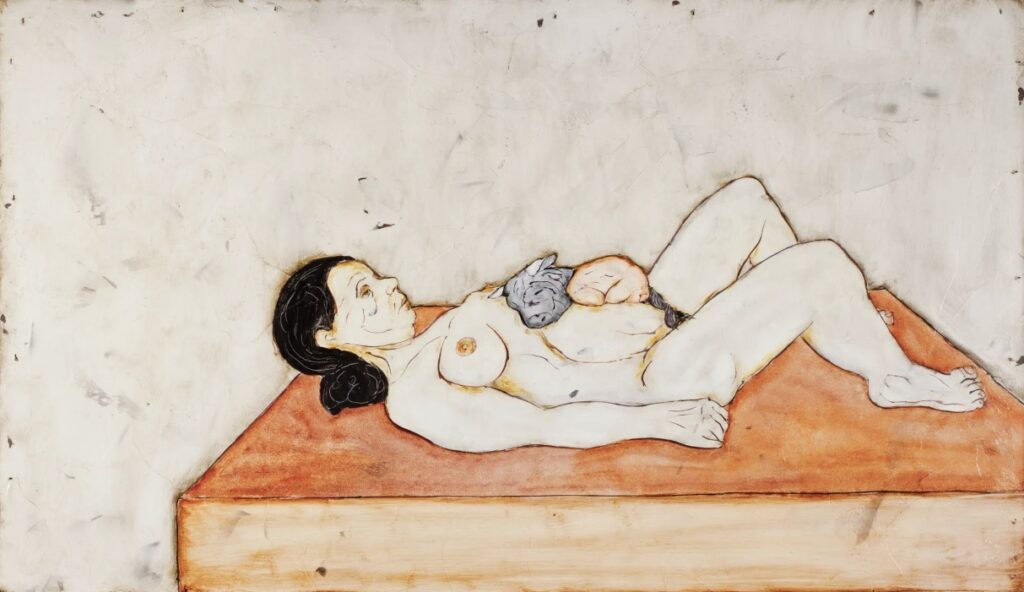

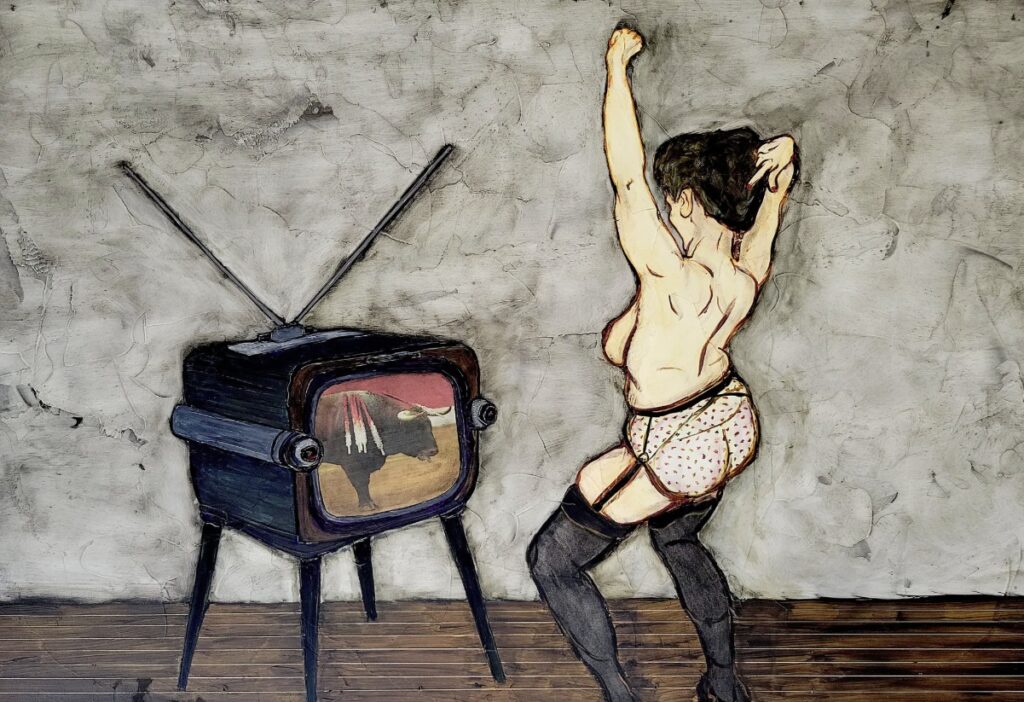

Steven’s paintings – he is self-taught – can be both grotesquely hilarious and highly distressing. Utterly glamor-free nudes, bull heads, trash TV, and the grotesqueness of the ordinary American family fill his canvases.

The paintings have appeared as book covers, in online journals; have been hung in galleries and alternative art spaces, and included as part of academic conferences.

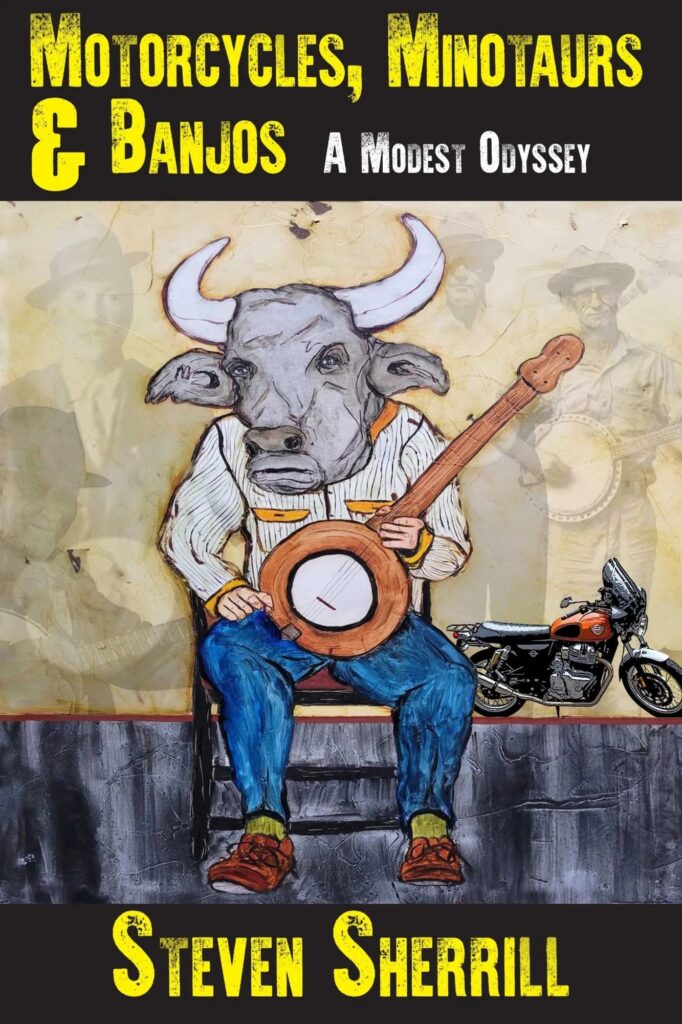

Following his muse and love for the open road, Steven recently took a 2,500-mile journey on his motorcycle down the spine of the Appalachians. Playing his banjo and singing at the graves of great American folk musicians. Paying tribute to the long aural shadow they cast. A trip which inspired his 2023 tome ‘Motorcycles, Minotaurs, & Banjos: A Modest Odyssey.’

Published 2023 by Road Dog Publications.

And then there is the Despondent Man, for whom Steven acts as handler and wheel-man. This nearly mythic figure has appeared in hundreds of locations, bearing the psychic weight of all who dare to gaze on him and cross into his world.

The Despondent Man also sat in my living room with us during our interview, though he said not a word…

TM. Let’s start with the Minotaur.

SS. I really have no idea why that title phrase came into my head when it did.

“The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break” came to me as one piece. As a title. I knew right away I wanted it to be a title.

The phrase came in as I was crossing on the bridge over the Iowa River. I’d been modelling nude for an art class for about two hours. I was in graduate school. And that phrase came into my head about halfway across the bridge.

By the end of the bridge, I had the premise.

You had just left your modelling job! Is there any connection?

I really don’t know how the Minotaur found his way to me. I really don’t. He just horned his way in and became a presence.

There’s no reason he should have come to me.

It took a long time to I learn to talk about him and his character and what it means, the thematics and the symbolism. And as a creative person – I’m sure you understand this too – sometimes it feels like we are just gifted.

I’m not a believer in anything, anything really. But I’m believing in the gifts.

Is it the unconscious? Is that where the gifts come from?

I don’t know. You can’t say.

How are you going to go there if you’re a non-believer?

I don’t dismiss.

I don’t know.

There’s something like the Jungian collective unconscious.

But that’s irrelevant to you?

I would never say it’s irrelevant.

I think I’m trying to navigate that space where I can say I don’t believe in anything really, but I’m open to almost anything. Like wiggling through that space. Because you can’t really make a claim.

You just can’t know what comes from it.

You can posit all kinds of bullshit, but you can’t know.

Some people might say, “I don’t think there’s anything beyond the physical world, but there is obviously a subconscious in my brain.” And some people say that’s where it comes from.

The subconscious is this bubbling sump of energies – But Jung went way beyond that.

That’s not you, though.

I find that fascinating, but I find being present to the possibility more productive than trying to figure it out.

The reason I ask about the link is the situation when the Minotaur came to you. I’ve not seen all of you, but I’m guessing that you wouldn’t make it now onto the cover of Men’s Physique magazine...

I was very fit at the time, but mostly modelling classes want imperfections in them.

It was always very funny.

I think it taught me a lot about art as well because I would, between breaks, I would put on a little gold bathrobe and go around and look. I went to Goodwill and I still have that thing. I bought this really schmaltzy gold bathrobe.

I would go around and listen to the teacher’s critique of this stuff. And they were good. So, it got me really good.

I was just thinking about questions of masculinity because the minotaur is hypermasculine, right?

Is he always nude?

You mean in classical representation? I don’t think I’ve ever seen him clothed.

Do you know that whole Picasso series?

And the minotaur is always very muscled.

I wrote this poem, ‘The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break.’ It was three years later before it became a novel. And the whole time I was writing the novel, I had one of these Picasso minotaur drawings taped to my computer and one by this fabulous British painter, George Frederick Watts.

His minotaur is looking over a parapet. He’s just looking this way with that little frail human eyeball. And that’s what it was about.

One of the trajectories of my life was coming from being a very shut down, very shy, guarded, insecure, human to someone who charges forward and hurls himself at the world and I don’t really care.

So, those two images. And a paragraph by Annie Proulx. The last paragraph of ‘The Shipping News.‘

I like the book a lot, but the last paragraph, the very final scene was my tonal emotional target for the final paragraph of the Minotaur book.

I didn’t know exactly where I was going to be detail-wise, but I knew tonally where I was going to be.

You’ve said that you hurl yourself at the world, and you use the word “furiously.”

Furiously, though I’m not really an angry person. It’s an energetic description. So hurling yourself, and furiously creating, furiously making, making stuff.

It’s not about anger, it’s about energy.

Are you tired of Minotaur questions?

Not at all, because they lead other places.

All the things that you mentioned, they’re integrated in the way that my brain works all the time. It’s been kind of an evolutionary ongoing project that sometimes has a horned character and sometimes has a rigid mannequin character.

Does it ever bother you that probably your biggest success was your first book?

It’s a thing that I have navigated. But it’s never going to get in the way of what I make the next time.

I was just well placed at that moment. It came out in 2000 but by 2005, everything in publishing was upside down. I got a lot of money from my second book. It didn’t sell. But after that, the publishers just don’t do the same thing. Everything is digital.

Everything changed after that Minotaur book, in the publishing world, everything.

When I wrote that second Minotaur novel, my fifth novel, many years later, it was not a continuation. It was not a sequel. The Minotaur Takes His Own Sweet Time. It was the same character, same deal, same issues.

I think I gave him more opportunity for love in the second one. I don’t really remember the content of that book. But I was actively not trying to say and “then the Minotaur did this.” He’s a Civil War re-enactor, so his kind of job is to die. He’s paid to die. He’s immortal, so he wants to die, so he’s relishing this.

Published in 2016 by Blair.

Do you remember in childhood or as a teenager, whenever you first noticed the Minotaur?

I was never a reader of fantasy. I’m sure that before this idea came to me, I was watching ‘Jason and the Argonauts‘ and ‘The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.’ Ray Harryhausen films. So those things were in my head, in my consciousness somewhere. They weren’t so far away, but I was not a heavy-duty fan of that kind of stuff. So, it wasn’t present.

As a kid, I always had lots of big ideas. Kept notebooks, kept all these ideas. Dumb little juvenile childlike ideas. But I would make lists. I would get the Sears catalogues, the Christmas catalogues, all the Sears things, and I would design my basement as a game area for kids, which included lots of sex games that nobody would ever play with me.

I would design that same basement or some space as like a workshop. Design or plan out a whole – I haven’t thought about this in decades. I think I made a plan for an entire Chihuahua-based daredevil show. Just dumb, crazy stuff.

I learned to make things. I taught myself to make things. Like a practice. But it evolved into the kind of imagination that I have.

It took me a long time to actually start making things. But once I did, I started writing.

Then it took me a while to start painting. But once I started, I started, and it took me a while to start making noise.

And now if I get an idea and I have the means, I’m going to make it.

So it was the writing of the words on pieces of paper first. And then visual images and then something like music. And then that bleeds into moving images, film.

I don’t make a distinction in my head about whether one medium or format is better or worse than the other. Just whatever occurs to me, it’s going to happen.

I have far less skill as a painter and even less skill as a musician, but I don’t value the results any less. It all serves to balance. Like when I run out of words, my creative energy doesn’t stop. So painting or sound is where I go.

If I finish a thing, I finish it. If I don’t, who cares?

It just feels like this big space filled with potential and no stress. I don’t feel urgency.

Let’s see if we can bring the Despondent Man into this…

Do you remember his origin? I like origin stories.

Yeah. I like those moments, too. But I think the kind of gifted arrival of the Minotaur stands out more than almost all the others. There are moments in other creative projects when things coalesce.

I can’t recall having the thought, “I’m going to get a mannequin and do it.” It just kind of… something occurred to me and I started looking.

But didn’t you already have mannequins?

I had a dressmaker form, this clear semi-opaque kind of this thing with a big Minotaur head on it.

That’s it, though?

That’s it. But I had the idea.

I don’t remember when the name came in – came to me.

Initially I bought a different mannequin that turned out to be… they sent me the wrong thing. I bought a seated mannequin from something called Yanks’ Mannequins, which provides mostly for military museums. So you get all these mannequins in war postures. But what they ended up sending me was a kneeling mannequin. And I didn’t want that. So I just started looking. And Despondent Man was an idea that evolved within a short period of time, so I don’t recall a distinct ah-ha.

I recall getting… like seeing – You know, I don’t know if I ever showed you what Despondent Man’s face looks like under that mask. He’s like this soccer player with very grey skin…

But I knew the posture was exactly what I wanted. And then I found this old man mask.

There were a lot of little ah-ha moments. I saw the posture. Yes, that’s it. I saw the mask. Yes, that’s it.

And then it was gluing foam rubber to the face so I could put the mask on.

And then the suit – the suit came together quickly at a thrift store in Altoona.

Your golden robe for modelling and the Despondent Man’s whole get-up, both from thrift stores!

But back to the posture – you didn’t put the mannequin in that position?

No. That’s his posture. He’s a sports mannequin sitting like this. Looking all jockey.

He’s a sports man. He’s supposed to be modelling sports clothes. That’s why he looks the way: Despondent.

He looks so – so much weight.

What about his valise?

That’s essential, right?

He has a Post office box in another town. I go there to pick up his mail, but I never, ever, look at it. Everything goes into his valise, anything you want him to carry. I have no idea what’s in there.

I will carry the Despondent Man for as long as I can and he will carry your burdens, until the end.

That’s the strongest thing for me. There’s so much weight but we don’t really know what the burdens are that he carries.

Are you asking do I sort of imbue him with a life? It is definitely my project. Definitely a project that I have made. So I have ownership over this project.

But I literally have no idea what’s in his valise. I will never have any idea what’s in his valise at all. I’ll never talk about it.

You’ll never talk about the contents of the valise or just that it exists?

Both.

If there’s something in there, I wouldn’t know. But I don’t – I mean, I don’t know how to answer that question. It’s just that there’s no…

It’s again, it’s like a seamlessness. I recognize that I’m the maker of this thing. I recognize that it has profundity to some people. And that kind of thematically ties to all the stuff we’ve been talking about and what my work is after.

The pleasure was in having this idea and realizing it out of things that weren’t quite there. The suit, the hat, the shoes, the valise. Underneath what you see he’s something completely different.

Underneath this façade that I created he’s something totally different.

Is there anything underneath the minotaur’s head?

Just a human. Fully human, fully inarticulate.

Well, there’s a fully articulate human in his brain who can’t get the syllables out over his fat tongue.

I know how that feels. I used to assign a book called ‘The Demolished Man‘ in one of my classes. It’s a great science fiction novel from the 50s – ‘The Demolished Man’ by Alfred Bester. He did two books way ahead of his time.

The name gets tangled in my brain and I keep calling him The Demolished Man when he’s really the Despondent Man.

Those are different things, very different. He’s not demolished. I would even say he’s a little bit Christ-like in his despondency. Like he will survive. His despondency is not going to crush him as I see him.

I don’t know how other people see him. But you know he’s just going to bear whatever comes his way.

And I see dignity.

Yeah. That’s what I intend anyway.

It actually affects me and I have seen him affect lots of people in different ways.

I do remember the last time you were in town, when we were in Mount Hope Cemetery, and we were pulling the D-man around the graves in his little red wagon, and there were some other people in the cemetery. And one of the reactions was discomfort and a little bit of a giggle like, “Oh, these guys are wacky.” I gave them a dead serious look and said, “You do not see this.”

You were probably busy setting up, and I responded to these people with as much gravitas as I could muster. No one asked me, but I told them, “You do not see this.” And that was it. Their response was sort of like, “You’re right. This is a dream.” So other than that, I haven’t seen… I don’t know how people react.

People are startled, and the sort of uncomfortable giggling has often come out.

Like when he was at this annual musical festival in this place called Rhoneymeade. There are grounds with sculptures and gardens and sitting areas. So Despondent Man was there for the duration. He sat in this place for three days. And I had a little microphone tucked inside of him. And I recorded a couple of things, including some kids who were doing karate on him, which was fine because kids are fearless once they realize he’s not real.

But then there were some people talking to him seriously. I had a little description there, just a little one, and then I had a QR code with more of a description. So, his explanation was there if you wanted to go for it. But there was always an element of respect and the respectful distance and curiosity.

I think people love the visual project of the photographs, too. I think I’ve developed a good eye for that composition. He’s just another one of those things that I have turned my eye of composition toward. I’d like to do a coffee table book, maybe.

And I think I talked to you about the possibility of a female, but you and other people have said that part of his power is his solitude. You said some version of that. And other people did, too. So I probably won’t. For one thing, it would add a piece to the story that would then cut off.

I have a little bit of a story in my head of who he is. And I’ve noticed him in this place, in this position, in all these places.

There’s almost an unlimited number of storylines with a woman too. Then it’s his wife or his daughter or whoever, but then he gets more limited.

I would like to get a female mannequin to have him in some other capacity with this thing, but not as despondent. In the play that I wrote, he’s not despondent. He’s Character. No name – just Character.

That raises another question. I wondered about name versus no name and title.

What he has is a title, in a way, like a superhero. Like the Atomic Man or Iron Man. There are lots of superheroes that have those kind of titles, rather than names.

So it makes me think – and I don’t know if you care much about this, or care much about Spaghetti Westerns – but there are lots of them that have characters with weird names or no names at all. There’s one movie called ‘The Great Silence.‘ The main character never speaks and he’s just called Silence. Lee Van Cleef is Angel Eyes. Clint Eastwood is The Man With No Name, etc. And there’s this idea that some film nerds have floated, that those characters are sort of like an ancient race. Immortal, like the Minotaur. There’s only a few of these guys left. And they’re superhuman in a way, because what they go through would kill anybody. But they just keep coming back and surviving.

So similarly – it makes me think that there are echoes of Spaghetti Westerns. I’m not saying that there’s in any way a direct link. But that’s what triggered in my brain. He’s got a title and no name, he’s got gravitas, he keeps traveling, he’s tough as hell, he doesn’t have a home.

I think of him as being a traveling salesman with nothing to sell. He’s got the valise which is sort of like a sample case. He shows up everywhere. He appears all over the place. He looks like he’s been trying to sell crap for a long time. And it’s been a really hard day. And he didn’t sell very much crap, whatever it is he’s got.

Do you know the Maysles Brothers documentary ‘Salesman‘ about the Bible salesman? I’m sure that probably subconsciously informed everything about this project, because I love that movie. It’s about just door-to-door Bible salesmen.

So poignant and so sad.

‘Salesman,’ 1969. Self-funded. About a hundred thousand dollar budget.

These are real salesmen. Very powerful.

But they’re putting on a show of sorts.

They learn the ropes and have to present themselves a certain way to make a sale.

Right.

Which brings us back to masks and appearances.

Do you do much costuming of yourself?

No, I am very uncomfortable in any kind of costume. I hate Halloween. I hate pretending to be something I’m not. I don’t like Halloween masks. I don’t like performing.

I’m not uncomfortable exposing myself, so it’s not about that. I like masks. I just don’t like to have them on myself. I like peeling away other people’s masks. I don’t like to do that myself.

Before I knew I could write or do anything else, I wanted to be a chef. And I really liked the costume.

The Minotaur has a very careful chef’s costume. He’s described like me. I wore a kerchief around with a bone snugged up against it. And I liked that. I like uniforms sometimes.

I pay attention to the dress and costuming of my characters very closely and the details, at least to me, to some degree, inform the character of their narrative. So it’s all very careful.

I like the visual of all that stuff.

Photo by Britt Bailey.

Uniforms?

Did you have any interest in being in the military?

Only a fleeting sort of what the hell am I going to do with my life? This might be a solution. But not a real –

It wasn’t part of your fantasy world?

No, no. I don’t ever want to be told what to do. And even as a kid, I would not be a rule follower. I have no desire to dress up as anything. I even have a hard time, though I’m getting better at that, dressing up in really nice dress clothes to go out. One thing that makes me mad – every single time, and I have no idea why – are these city magazines or all these town magazines where the gala photos are at the back and all these people are so smug. It makes me want to shoot everybody on the page. Why are you standing there – why not just go away? It’s an unnatural overreaction. I don’t know what it’s based on.

Is it social class?

It may be class. Because those are people either wannabes or have real privilege.

They’re in a different social class than you grew up in?

Absolutely.

So, social class is something you think about?

Of course.

All of my characters in all the books, are very working class. I actively think about and write in response to that. It’s not just the privileged people who have stories worth telling, or struggles that these working class people, these regular people have too. I’m actively committed to the stories of the lower classes.

Like, ‘The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette’: it takes place in a restaurant that I worked in. All these other places are North Carolina, Pennsylvania towns that I grew up in, that I live in.

I don’t have interest in the world of privilege in my art.

Released by Orb Tapes.

Do you ever think that that has an impact on readership? Because most people like to read about the rich, and the poor people tend not to show up in popular fiction unless they’re grotesque and disgusting.

Right – It doesn’t mean they’re not interesting. And especially to make the regular, lower, middle working-class human life interesting is a fun challenge. Again, we’ll circle back for this part.

I think everybody has a level of depth and complexity somewhere. You might have to peel away years of squashing by the man, but it’s there.

Can we talk about the suffering in your books?

Your characters are making their way in a very hard world.

I’m softening, and I want to be softer.

That’s something that I have to figure out how to do.

Does that connect to your recent book, ‘Killers’?

What made that possible for me was in the end, the violence is deflected.

The point of the book for me was there’s very little difference between this kid with his rifle about to shoot everybody and the kid down there bullying somebody at the pool. Just a few degrees of circumstance separate them and push one in the other direction. And it’s all around, and it doesn’t mean you have to be afraid of it or that should dictate your life, but if you are aware of it, you become more open to possibility to taking care of these kids.

But I could not have written the shooting scene. I wouldn’t have done that. I couldn’t write ‘Joy P.A.‘ again. That’s a hard one. I know it is. But I don’t hold the content of the books in me.

I’m sure there are brutal moments in almost every book that I just don’t remember.

Published 2015 by LSU Press.

So this isn’t about confrontation, you versus the world?

I have no desire to write or even make art, visual art, with the goal of disturbing. It’s never about disturbing the viewer, the reader. It’s about the integrity of the story I’m trying to tell.

I have arguments with people occasionally and imagine many more about the ridiculous content of my paintings. They’re just so funny and absurd, but if you are of a particular bent, you’re going to get mad at me. I’m not tolerant of that.

You’ve had to deal with some angry people at art shows?

Yes. My paintings were on the wall and somebody asked, “Were you not breastfed?”

These are not real people, first of all. What I intend is what I intend, whatever you project is what comes from you – so if you don’t like it, go away.

I had a friend who I respect and like, and we were talking about making art and he was saying, “An artist can make anything they want as long as they’re willing to get up and defend it or discuss it.” I don’t think that’s necessary. I’m going to make the stuff that I make.

So a person comes to an art show and looks at a couple of paintings and sees a pattern and finds it disturbing, distressing, and starts then projecting onto it psychodynamic stuff that may or may not have anything to do with reality. That’s that person over there. And I’m over here saying, “Look, I just made this stuff, and I don’t really want to defend and discuss it with you or anyone. Not only do I not want to, I don’t have to, and I’m not going to.”

If there’s hostility and challenge coming towards me, I’m not interested.

If it’s a genuine questioning, I love to talk about process. I love to talk about how I did this stuff. But even more so with visual art than with writing, I am completely uninterested in the psychoanalysis of my paintings. I have a gut-level understanding of narrative tension and visual tension, and I’m just having fun doing this.

I find it tedious and distracting, a waste of time, to discuss my psychology in these paintings.

And it might even also drain some of the creative energy.

That’s exactly what I mean. It’s just energy spent somewhere. I’m not going to do that.

I’d love to talk about where I got these images and why I see this working and what I see as the tensions, but as far as question like “did your uncle pee on your foot when you were a kid and make you do this?” Who cares about that stuff?

If you’re in psychoanalysis or you’re in psychotherapy, you might want to talk about your uncle’s peeing on your foot. But you’re making paintings!

Exactly. There’s a different place for that.

I’ve had these imagined arguments in my head many times, so it goes in lots of directions. For a viewer to assume that I’m troubled in this way or need to work something out, the presumption is that I’m not working on myself because they are not seeing it. That’s a different part of my life. This is painting. And you’ve come to a gallery.

I had this argument with some friends the other day about stand-up comedy, particularly caustic hard comics, in your face comics. From my perspective, at a comedy show, there’s nothing off-limits. You go to a comedy show, you open the door. That’s what it’s there for.

That’s one of the purposes of deep, good comedy. There’s nothing off-limits.

And that goes for your work too?

I intend respect to all the people that I brutalize in my books in the same way that I intend respect to all the saggy tits in my paintings. There’s no disrespect behind my actions.

And when I make the bad guys really bad in the books, there’s always humanity somewhere. That’s the most important thing for me. That sort of humanizing the bad guys and making good guys fallible also.

The Minotaur and the Despondent Man are human and yet not human. And some of your fictional characters are so extreme that they raise the question of what makes us human. It’s not just A.I.s and robots and animals; it’s also the dead and the living.

At what point does this thing that’s talking right now stop being human? Eventually, this hunk of meat sitting in this chair is going to stop being alive.

But it’s still human.

So, would you call a corpse human?

I would say is the question relevant?

What’s the difference?

The memory still exists. The memory’s not going to go away. Our books are going to stick around.

We’re momentary; we’re a blip. I go in and furiously make stuff. Some of us go in and furiously do a lot of damage. I don’t think it matters.

But you said the memory continues.

For a little while, then it would go away too.

Your wife and kids will remember you. They’ll probably outlive you.

And if your kids live long enough, they might have kids that know you.

Or some of my Minotaur books might stick around for a while.

But I don’t think it matters. I don’t, I genuinely don’t, think it matters.

What all of that is about is, I think, is a very Buddhist precept. If you’re regretting your past or worried about your future, you’re not in the only place you’ve really got.

At the same time, I couldn’t ever deny that the success of that first book made the rest of my life possible. And the ego satisfaction of its success and the scale of its presence still in the world, it allows comfort in other ways.

But the place that I feel most present in the moment is making. Which means if I can stay focused it doesn’t matter whether it’s good or bad, or if it’s successful or not, and even if it’s successful, it doesn’t matter.

You can just make it your next thing.

It’s all about being present in that moment.

Links

- Steven Sherrill – Website

- Steven Sherrill – BandCamp

- Steven Sherrill – SoundCloud

- Steven Sherrill – Instagram

- Steven Sherrill – YouTube

- Steven Sherrill – GoodReads Entry

- Steven Sherrill – Discogs Entry

All images supplied by Steven or sourced online.