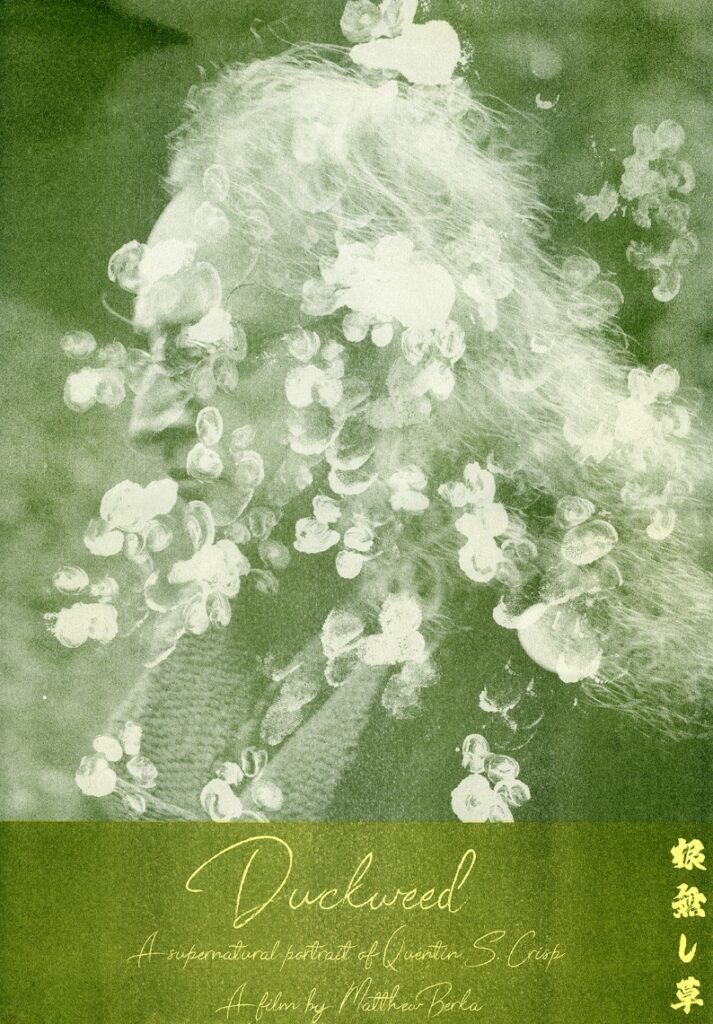

Quentin S. Crisp is a British writer of fiction, essays, and poetry with some two and a half decades of publications to his name. He has been shortlisted for The Shirley Jackson Award, has been mentioned in The Spectator and is now the subject of an independent film, Duckweed, by filmmaker Matthew Berka.

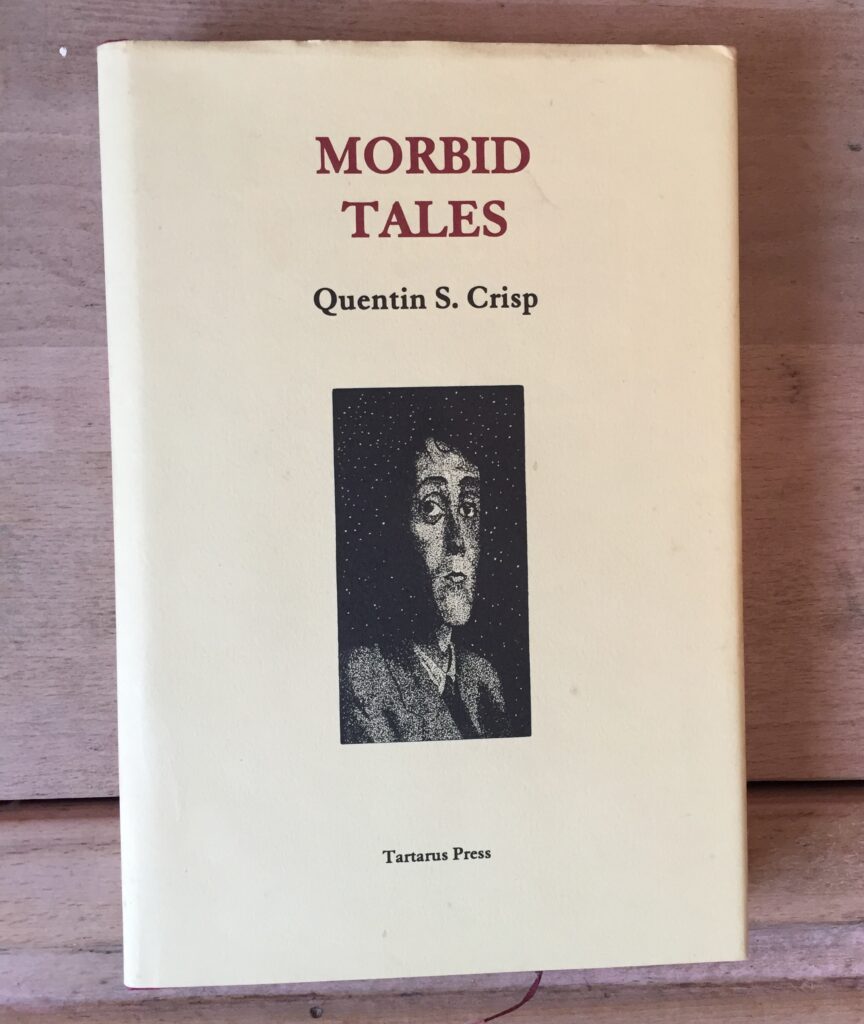

His second collection of fiction, ‘Morbid Tales’ (2004) has been described as “a cornerstone collection of modern weird fiction”, he was one of those behind the founding of the much-missed Chomu Press, has collaborated with Justin Isis, a leading figure of the Neo-Decadent movement, and with avant-garde author Brendan Connell, and he has a strong claim to being the writer of the first English-language I-novel.

Yet despite this welter of accomplishments, honours and associations, Crisp remains, as far as the consciousness of the reading public is concerned, terra incognita, a strange, literary chimera still awaiting discovery and taxonomical identification.

Along with a copy of Quentin’s 2004 collection, ‘Morbid Tales’; published by Tartarus Press.

Who and what, then, is Quentin S. Crisp?

Born in 1972 in North Devon, a rural part of England whose scenery has cast a long shadow on his aesthetic development. He entered university late, in 1996, to begin a degree in Japanese Studies. He spent the second year in Japan and graduated in the year 2000.

Immediately after graduating, he travelled to Taiwan to teach English. It was while he was there, in 2001, that his first collection of fiction, ‘The Nightmare Exhibition’, was published by BJM Press. The collection received little attention, although one story, “The Psychopomps”, was the subject of favourable comment from Thomas Ligotti.

‘Morbid Tales’ followed, from the prestigious Tartarus Press, in 2004, with an introduction from the now well-known weird fiction author, Mark Samuels, who sadly passed away in December 2023.

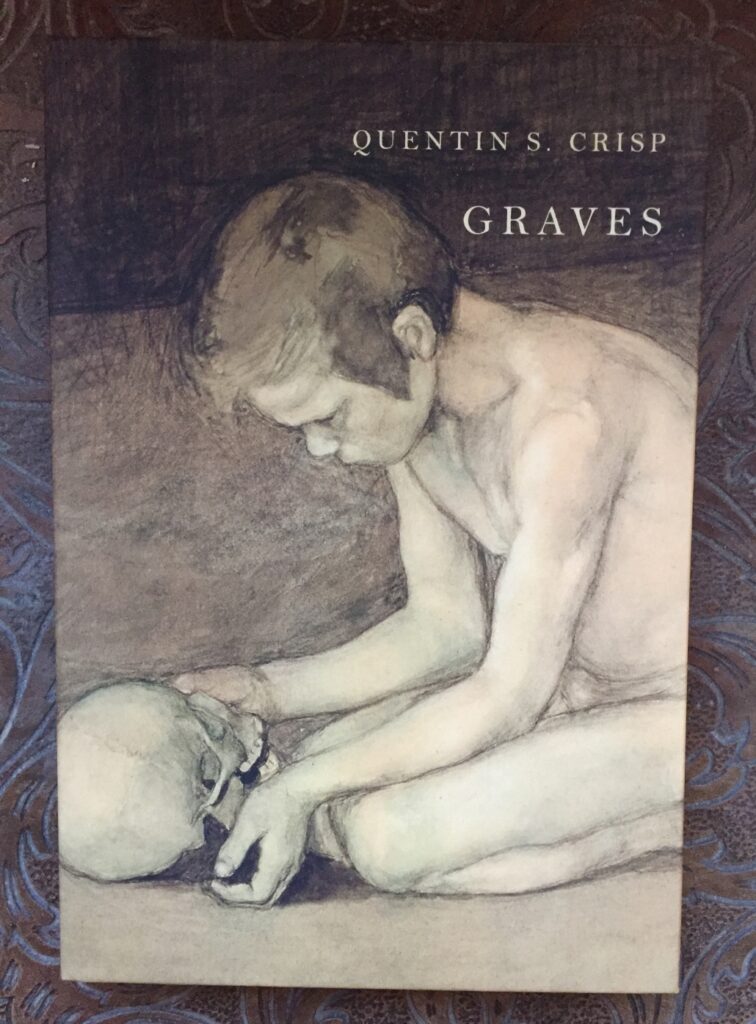

After a sporadic beginning, Crisp’s publications have settled generally into a steady stream so that now his standalone titles, at a conservative count, pass twenty in number. Notable among these are ‘Shrike’ (2009), shortlisted for the abovementioned Shirley Jackson Award and combining the Japanese I-novel form with supernatural themes; the urban gothic novel ‘Graves’, a polemic against contemporary death-denial and a serious fictional take on the hard problem of consciousness; and ‘Autumn and Spring Annals’, a calendar-based and diaristic collection of poems in the Japanese tanka form but with an English sensibility compared, by Justin Isis, to Philip Larkin.

Along with a copy of his book ‘Graves’; published in 2019 by Snuggly Books.

While continuing to build this body of work, Crisp was also editor for Chomu Press, who released debuts from Justin Isis, Luke Geddes, and Daniel Mills. As well as publishing an eclectic mix of other contemporary authors. As if this weren’t enough, Crisp has had a longstanding collaboration with Serbian band Kodagain, for whom he has written lyrics now numbering in the hundreds.

I hope that the following interview manages to pull some of these varied threads together to give a more focused view of Crisp’s creative identity and the influences and motivations behind it.

It came about in the following way: After enquiring of a friend whether there were still any British writers worth reading, I was sent a copy of Crisp’s ‘All God’s Angels, Beware!’ I was impressed enough to read more of the author’s work, but it was not until I had read ‘Shrike’ and ‘Blue on Blue’ that I was sure I had discovered something special. A while after that, I made contact with Crisp, and later I started the Quentin S. Crisp Appreciation Society on Facebook.

We naturally spoke about the possibility of an interview.

Crisp said he would like to try an interview in person, as most of his previous interviews had been conducted remotely and he wanted something more like a conversation. I agreed. After a date was set and recording apparatus was prepared, I visited Crisp’s flat in southeast London.

Tea was served and I put my questions.

It should be noted that the interview was conducted in November 2023. Various life issues led to delays in transcription and editing with the result that some things referred to as future events may no longer be so….

So; I am sitting here in the London Borough of Bexley, a billowing grey sky outside the window, of the sort that can only exist in England, with the author Quentin S. Crisp.

KM: You have made yourself relatively inaccessible compared to a lot of other authors in this new age of the internet.

Is that a deliberate choice?

QSC: Not exactly. It’s not that I thought, “I want to be inaccessible.” I think it’s partly temperamental.

I actually am quite shy, and I . . . I suppose you’re talking about social media; is that right?

Yes.

Um . . . and . . . also social media . . . I just don’t get on with social media very well. It’s not that I can’t enjoy it, but it seems to be . . .

I find it frustrating. And I don’t seem to have the kind of personality for self-promotion through social media. Maybe I can promote myself in other ways, but not through social media.

That, that sort of . . . the fray, you know, the digital fray, I find it disagreeable. Having said that, there is partly an element of calculation because . . . um . . . I also don’t like this default internet aesthetic that authors, living authors, seem to take on of being these super-approachable ‘relatable’ citizens of the 21st century, with these “I’m just a crazy, cat-loving geek” sort of author profiles, and this sort of thing.

I don’t really like that at all.

I mean that’s not how I want to think of, I don’t know, Mishima or any of the authors I enjoy reading, so from an objective point of view I . . . I also don’t want to spoil the enjoyment of my readers by being some sort of approachable internet geek figure.

By sort of putting your face in front of all your work all the time?

Yeah.

There was an intense scholarly debate about what exactly an “I-novel” even is, assuming it requires a kind of essential lineage to the first Japanese I-novels, ‘Futon’ and ‘The Broken Commandment’, assuming it is a quintessentially Japanese form of novel – and I should add here that the Japanese term, “shishosetsu”, does not distinguish between novels and novellas.

There is at least a case to be made that ‘Shrike’ was the first I-novel written in English. Your novella ‘Erith’ is subtitled “an Anglo-Saxon I-Novel”; you are yourself a kind of English I-novelist. Of course, you do more than I-novels.

Would you mind saying a bit about what exactly an I-novel is?

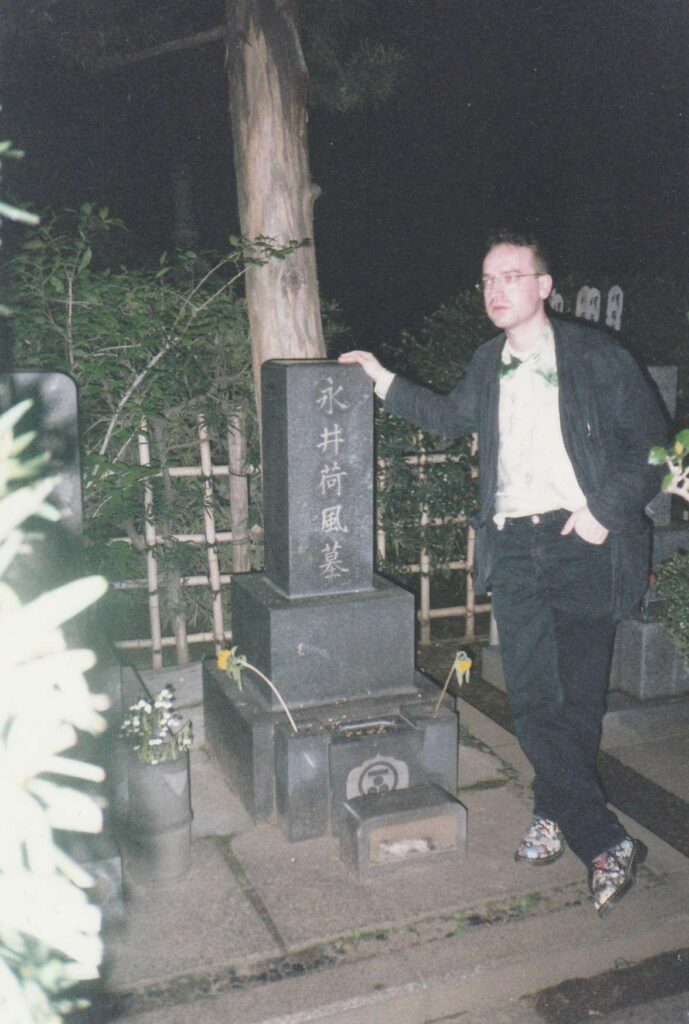

Yes, well I . . . I don’t have a definition so . . . my influence is by example. So, Tayama Katai’s ‘Futon’ has influenced me, but I think my I-novel influence is actually a bit diluted because I get it mainly from Nagai Kafu and from Dazai Osamu, who I think are not considered pure I-novelists. Both of them are a little bit romantic, in fact, but Kafu started out influenced by Zola, so that’s similar to the naturalist school in Japan: they were influenced by Zola.

Japanese naturalism, which is associated with the I-novel, is influenced by French naturalism, and so Zola. So you have that influence with Kafu. But he became more a sort of romantic, Baudelarian writer in a way. And Dazai Osamu . . . I think he’s often classed under the “Buraiha” label, which means something like “the Unreliables” (laughs), but it’s got a bit of a “Brat Pack” sort of feeling to it, if you can imagine that in literary terms.

Yeah, but anyway, the point is, I’ve got my I-novel influences mainly diluted through those two figures, I would say, and the elements are that there’s a lot of first-person work and it’s about daily life really, so it’s not strong on plot. It is fiction, so it’s not just autobiography, but it can feel sometimes just like autobiography. But I particularly associate it with the Japanese aesthetic of the everyday. And there’s a line in Okakura Tenshin’s ‘The Book of Tea’ which is something like, “The Japanese . . .” or possibly he says “Orientals”, but anyway, “The Japanese have made a romance of the everyday.”

So if you think of Western romanticism, it’s all sort of climbing mountains and storm clouds and stuff like this, but this is saying there’s . . . for the Japanese there’s a romance of the everyday, which you see in things like the tea ceremony, which is the hyper-aestheticisation of something everyday and normal. So for me that’s what the I-novel is.

You mentioned romanticisation of the everyday: your novella ‘Blue on Blue’ strikes me as very obviously in the tradition of the I-novel, albeit through a kind of reapplication of the techniques of the genre in the world of pure fantasy, imagination and science fiction, with the protagonist Victor Winton as the subjective focal point for the story in this amazing alternate world.

Was this deliberate?

No, it wasn’t. I mean, you pointed this out to me, and it’s an attractive idea. I think it’s very probably true that I am basically doing the same thing in ‘Blue on Blue’, which is a sort of a whimsical science fiction, retro fantasy, the same thing in that as I’m doing in something like ‘Shrike’ or ‘Erith’, which are much more drab, everyday settings, and I suppose it’s to do with the idea that I had fairly early on in my writing that I really want to reproduce the sense of what it’s like being here, existing in the first person, that I wanted to reproduce that in writing, so that writing becomes a sort of virtual reality for pure consciousness, as it were, like you ‘just add consciousness’ to the words and you get a virtual subjective experience from it.

So, not like watching a film, because you have the subjective element. And I suppose that’s my basic approach.

I wouldn’t say that I never leave that behind, because I don’t want to limit myself, but wanting to get that effect has been a very, very strong motivation in my writing.

That’s very interesting.

I’m gonna switch gears for a moment – This interview is for a magazine that advertises itself as, “illuminating the culture underground.” You were somewhat dragged into it by mentions by others.

Do you feel that you have much kinship of situation, of aesthetic, of interest and so on with the underground as it presents itself?

Well, I mean there’s more than one underground, surely? There are many different undergrounds, I’m sure.

I mean, I’m certainly, culturally speaking, under the radar. That’s for sure. And, you know, I’ve grown up with a lot of counter-cultural stuff. That was always where my interests lay in music and in literature. You know, when I say “counter-cultural”, I suppose I basically mean non-mainstream. There are people who use “counter culture” with a political meaning which I am not intending here.

And, well, there are other elements like this in my upbringing. I have in many ways been on the fringes of things. So, you know, I don’t feel affronted by the idea that I’m underground. I very often feel like I am literally buried, so in that sense I think it’s quite appropriate. But it’s true that there’re a lot of things that become orthodoxy within an underground movement, and usually we’re talking about political things but not always, that I just don’t subscribe to.

I am very much a person who looks to the past rather than the future, and so this, I think, sets me apart from a lot of people who think of themselves as making underground art and so on.

My roots are in the countryside. I don’t feel like much of an urbanite. I mean, I suppose by now I’ve lived on the outskirts of London so long that maybe I’m fooling myself, but I still feel like I have roots in the countryside.

There are other elements like this which I think are not typical of people in, let’s say, in the art underground.

In some past interviews published by The Aither, you have been presented by others as a Neo-Decadent author. You have even contributed to some early anthologies calling themselves Neo-Decadent.

I am not entirely sure what Neo-Decadence is. I gather that it at least has some kind of connection with the early French Decadence extolling the machine and the artifice of modernity over nature and the past – Huysmans famously said the steam engine is more beautiful than any cathedral.

No, I don’t think he said that about cathedrals.

No, he said the steam engine is more beautiful than anything in nature.

In a recent article on neo-decadence (I meant to ask you about that quotation before we started) the author repeats a quotation making the similar claim that the internet is more beautiful than a cathedral.

In The Robot in your collection of Japanese-style essays, ‘Aiaigasa’, you write about robots as an “aesthetic menace”, part of an “Armageddon of the “unbeautiful”.

It sounds like you are actually positioning yourself against the Neo-Decadent aesthetic in this essay, like you reject the Neo-Decadent claim of the steam engine and the internet?

Yes, well, that’s true. I mean there’s not a lot for me to answer on that.

I do reject that claim, yes.

Okay, I guess that’s a brief answer.

You don’t think the internet is more beautiful than . . .?

No, no, I think the internet is extremely ugly. I mean, well, there’s a temptation for me to try and be nuanced here, because this is complicated, and I feel the dangers of falling down a rabbit-hole of word-salad.

There have been beautiful things about the internet, such as my collaboration with Kodagain. But such things seem to be getting scarcer, and what we have instead is surveillance, cyber-lynching and bulimia.

On the subject of Neo-Decadence, I’m not sure I have much to add to what I said in an interview I did with Justin Isis, one of the leading figures in that movement, on his blog around the beginning of this decade. Could I just direct people to that?

I agree with a lot of Justin’s criticisms of the current literary scene, but these things are so nebulous, one has to have very specific questions and get into the weeds, so . . .

Along with the now sadly deceased Mark Samuels in England, circa 2017

Would you mind saying a bit, if we might linger on the subject of ‘Aiaigasa’ for a moment, about the “zuihitsu” technique that you use in your essays in ‘Aiaigasa’?

You want me to say a bit about “zuihitsu”?

Yeah, keeping in mind that possibly a lot of the people reading this interview don’t understand Japanese, including me.

Yeah, well, zuihtisu, I mean you could just say this is an essay. The word is written with two ideograms: “zui” meaning “follow’”, and “hitsu” meaning “brush”, as in “writing brush”. So the implication is that the writer just sort of ‘goes with the flow’; they follow where the brush leads them, so to speak.

And so I think this kind of essay writing very naturally merges with the I-novel form, as well, because you follow your thoughts and your associations and that often brings you back to your own experiences in life and then those experiences lead you on to more thoughts, and so on. So I think that it’s that kind of style, really.

It’s not the style that we’re taught in Western schools, which is, there’s a beginning, a middle and an end; first of all, you have to tell us what you’re going to say, then you have to say it, and then you have to tell us what you’ve said. It’s absolutely not that form of essay. It tends to have a sort of flowing yet asymmetrical quality with a different kind of balance to the Western-style essay. It’s more organic, I’d say.

Having said that, if you read someone like, well, if you read Michel de Montaigne, who … I’m not a hundred per cent sure, but I think he’s credited with inventing the essay form?

He has been credited with that in the past, whether or not it’s a bit like Columbus being credited with discovering the New World.

Yeah, I find it a little bit hard to believe that he’s the inventor of essays, but anyway, he has been credited with that, and if you read his essays they’re a bit like Japanese zuihitsu, actually. They don’t have a beginning, middle and end in a neat way. They follow his associations of thought.

I guess that maybe the main difference is that Montaigne seems to regurgitate a lot of his erudition, a bit like he’s copy-and-pasting a lot of his reading in his essays, you know, which I mean, you can do that in Japanese zuihitsu; I just don’t think it happens as much. That’s a bit more distinctive of Montaigne.

I asked you about Neo-Decadence and quoted your essay; what about weird fiction?

Your weird fiction collection ‘Morbid Tales’ is now being called a cornerstone and classic of the weird.

You were first published in the weird fiction magazine ‘Haunted Dreams’.

You were in round robins with S.T. Joshi and Thomas Ligotti when the genre was still being fully formed.

Comfortable Lovecraftianisms show up in some of your earliest works.

Yet in more recent decades Japanese and science fiction influences have become more prominent in your corpus, and your work has grown like the branch of a tree reaching towards the sunlight, resolutely away from the weird. What is your relationship to weird fiction?

I don’t think S.T. Joshi was in the round robin. But anyway, that’s something to sort out later.

My relation to weird fiction … (long pause) … Um … well, the obvious thing is that Lovecraft is a huge influence on me, and one of my models for writing: the kind of Lovecraftian suspense which works by hinting that there’s something horrible and revealing it in a sort of striptease of, you know, macabre glimpses and so on, and you allow people to piece it together and in the end you reveal the whole thing.

So that kind of model was one that I learned to use, and it’s not just the structure, it’s the atmosphere as well that I have been influenced by. And it’s not just Lovecraft, I should say, but he’s the obvious one to point out.

I basically have an interest in the macabre. I’m not so interested in what I think is now called ‘body horror’ – just physical horror to do with people being tortured, maimed and so on; what I’m interested in is a dark, otherworldly atmosphere. It doesn’t necessarily have to be supernatural, but it’s something that takes you out of the ordinary and confronts you with the hidden regions of your own psyche – let’s put in that way.

So I think of the macabre – this is a label of convenience – as being wider in application than weird fiction, and I suppose I’d say that that’s really more my interest, of which weird fiction is a subset. But that’s a long-standing interest and I’m sure I’ll always be interested in that, possibly until I die, I don’t know.

I mean when I’m actually dying I might decide that I want to contemplate more cheerful things, I don’t know.

Does that answer the question?

I feel like I’ve been a bit vague.

I think you answered it!

Okay, so you still very much consider yourself involved with horror and gothic horror?

Yes.

There was a time, some years back, when I thought I’d try and put it behind me, but that didn’t work, so probably these themes will always recur to me.

Would you say that your work ‘Graves’ was an attempt to bring the techniques of the shishosetsu or I-novel genre into that aesthetic world of horror?

Not consciously, no.

No, I wanted to write a gothic novel really. I’m not sure that I’ve succeeded in making it completely gothic. Well, during the writing process I was aware of a problem with the aesthetic. It’s hard to sustain a pure gothic atmosphere in a contemporary setting.

So I decided to make that a feature and have the main character … have part of his motivation as that he’s fighting for the realisation of the gothic aesthetic in the modern world. So that’s how I dealt with that.

That’s very interesting.

We have a Quentin S. Crisp Appreciation Society on Facebook founded and run by some very handsome and clever fellow. I recruited some help coming up with questions from it. I did not really give them a lot of time to reply before conducting this interview so there was only one, but it is such a good question that I simply must include it…

Taryn Allan asks:

“There’s a very strong personal element to certain stories in Quentin S. Crisp’s bibliography, stories which seem like a deeply individual take on the Japanese I-novel, a sort of merging of the autobiographical with the metaphysical which produces for the reader an almost direct connection with the mind of the author.

Within this peculiarly Crispian form of narrative, has Quentin S. Crisp ever written any stories which he felt were too personal to publish?”

Not yet, I think is the answer. I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that I might.

The funny thing is, it is a kind of a struggle. I’ve often written things that I am very nervous about seeing published. And it’s not necessarily for the obvious reasons. You can feel sensitive about things because they’re very personal without it necessarily breaking some social taboo, at least explicitly. But then I’ve gone ahead and published those things, biting my fingernails, and so far nothing terrible has happened.

Yeah, and often the elements that I mask tend to be for the benefit of other people in my life rather than my own. So yeah, I think the answer is not yet, but it’s not impossible that there will be things that I feel that I can’t publish, and there’s very often a struggle, anyway, so that there is some uncertainty, possibly even each time I write, as to whether I should really publish something.

I mean, maybe it’s not every time, maybe that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but very often.

As a sort of coda to what I said about the internet, I have a theory that one reason that the internet is antithetical to literature is that is militates against the kind of intimacy that literature requires and fosters. Of course, this might be a reason that people wish to turn to literature more, rather than away from it.

But on the whole, people now feel the need, I would say, to live their lives wary of the fact that anything might ‘end up on the internet’. This is a hostile environment for human intimacy.

Thank you.

I opened this interview with a comment about the sort of sky that can only exist in England. Disappearing landscapes, disappearing worlds, feature very frequently in your work: in ‘Aiaigasa’, ‘The Flowering Hedgerow’, and the upcoming ‘Ikaho’, to name a few. They also feature very heavily in your long-running letter to your fans, which you are publishing in the form of a kind of epistolary essay online, ‘The Old Doctor Who’.

Would you mind saying a bit more about how this influences the work and about the creative impetus for this work?

Vanishing worlds and so on ?

Yeah.

So, could you just repeat the last bit?

Would you mind saying a bit more about the creative impetus for ‘The Old Doctor Who’?

Hmm. Well, I started writing something, I think back in 2014 (I can’t remember exactly now), under that title, and I got a few pages in. And this had been prompted by a visit to Chinatown in London when I couldn’t find the bookshop I was looking for there. Quite a nice bookshop. It turned out it had just moved address, but I thought it’d been closed down. And this made me feel quite sad. And indignant.

I think the emotion of indignation is important to this kind of thing: the sense of good things going because people are making the wrong choices. They are selecting for the rubbish and against the gold. I think that’s part of the motivational feeling behind this writing – this indignation. So, I wrote a few pages of that.

The title has a sort of Oriental symbolism. In other words, in Chinese and Japanese literature I very much like the use of symbolism in the titles of stories and novels and so on, and this is a little bit like that, because although I do write about the old Doctor Who in the essay, the old Doctor Who is a symbol, really, for things of my childhood that are either gone or vanishing.

Anyway, about four years back I had to move flat and I moved to where I am now. The rent was higher and so I thought I should start a Patreon account and I wasn’t sure what to use for it, and then I thought of that thing that I’d started back in 2014 about things that are lost or vanishing, and I thought: I can write forever about that, which is what I might need to do in order to pay the rent. So I picked up that again and I’ve been serialising that at Patreon.

The chapters . . . it is cumulative. The chapters do build on each other, but they also stand alone pretty much, I think.

I don’t know if that answers the question about motivation, does it?

Yeah. Yeah, I think it does.

Your latest instalments of ‘The Old Doctor Who’ actually have you unexpectedly traveling back in time. Whereas most of the essay is non-fiction this section blends the fantastical with the real. This is also a major theme in a lot of your work, stretching at least as far back as ‘Shrike’ and in varying forms and degrees through ‘Out There’, ‘Graves’, which takes place in subtly renamed parts of London, ‘Hamster Dam’, arguably in the aesthetic qualities you invoke in ‘The Flowering Hedgerow’, and arguably in other works, as well.

Would you mind saying a bit more about that?

A bit more about?

The theme of blending the fantastical and the real in your work.

Well, I mean that’s . . . you know that’s everything for me, really.

I hope I’m not repeating myself too much because I have said things like this before, but I started out wanting to write fantasy, by which I don’t mean sword and sorcery; I just mean the free play of the imagination. Although my models were secondary-world fantasy, you know, like Tolkien. That sort of intoxication of what the imagination can do, that’s really what literature meant for me at the beginning. But in trying to write that kind of thing I realised that I needed not just the gooey flesh of the fantasy, but I needed a skeleton to put it on, the skeleton of a kind of reality, and I didn’t really know what to do about that because I don’t think I know much about reality. I just knew I needed to find out something about reality in order to give a substantial infrastructure to what I was writing.

And so since that realisation I seem to have swung back and forth on a pendulum between the quotidian and the fantastical, and it’s not just a matter of writing technique. It’s strange how these two things come together. There’s also a sort of a spiritual or metaphysical question of how the two relate, and there’s a desire, a need to merge them in some way.

Where can people find ‘The Old Doctor Who’?

Er . . . at this link. Er, here on the internet.

And for those who support your continued work, you get something like 95% of everything paid into your Patreon?

Yeah. I don’t know the exact percentage, but it must be something like that . . . yes. And I’ve set the threshold relatively low, but people can choose to pay higher if they wish.

Right, and like the world which disappears – ah, how sad! – the material being hosted on your Patreon, ‘The Old Doctor Who’, too, might one day disappear and become out of reach to those who might otherwise wish to read it; especially given the instability of the format?

Yes, well, I do hope that one day it’s all bound together in printed form, whether in one volume or a number of volumes, as its length might dictate, but I realised going into the Patreon venture that I didn’t know exactly where it was going, so . . .

. . . the internet is ephemeral.

Yes. Yeah.

I happen to know you have quite a lot coming up in the next few years – possible career pyrotechnics. Do you wish to say anything about this here?

I’m usually very wary about saying what’s going to happen. There are plans and there are projects that are currently being worked on and I’m happy for most of them to emerge in their own time and possibly even to surprise people.

There is one in thing particular that I’d like to take the opportunity to mention, though, and that is a film, by the title of ‘Duckweed‘, that’s been put together by the film-maker Matthew Berka. It’s going to have a premiere in October and we’ll see what happens after that.

The title is the same as a zuihitsu I wrote. In fact, I’d had the notes for the zuihitsu for ages, but once Matthew started on the film, which was to be a documentary about, I suppose about me and my work, I suggested I write the zuihitsu up so it could be used as a sort of narrative element for the film, and that’s what has happened.

So, it’s a kind of documentary essay with sound and image being very ‘high in the mix’, so to speak. I think it’s very mesmeric and immersive. I’m very much looking forward to seeing what people make of it when it comes out.

Apart from that, for now I will just say that I plan to carry on writing for as long as circumstances – financial and otherwise – will allow me. I mean, you never know how long that will be. Being a writer is a lot more precarious than people think.

Do you expect there will be more interviews for the underground like this?

I don’t know, I mean, I do quite like giving interviews, but I do need a rest between interviews, I think.

And also . . . yeah, I suppose there will be. It depends if people are interested.

I’m looking forward to the trajectory of your life as a writer and your writing.

Thank you.

Links

- Quentin S. Crisp – Instagram

- Quentin S. Crisp – Patreon

- Quentin S. Crisp – Wiki Entry

- Quentin S. Crisp – Goodreads Entry

- Quentin S. Crisp Appreciation Society – Facebook Group

- Quentin S. Crisp Interviews with Justin Isis – via Justin Isis’ Blog

All images supplied by Quentin or sourced online.