Every high-school reprobate has heard of some home-remedy, DIY, MacGuyver-esque means of using household goods to nefarious ends, whether it was attempting to turn banana peels into a hallucinogen or converting garage-finds into guerrilla incendiaries.

Laws, parents, and community groups have struggled to keep ahead of the ingenuity of people, and any changes enacted tend to encourage further innovation.

Banning drugs creates a market for drug analogues.

Banning drug analogues creates a market for a further expression of that ingenuity.

Something a little harder to see…

Two changes in legislation were introduced in Australia during 2019 and 2020, targeting seemingly innocuous products sold for regular household uses, that have attempted to quietly change the drug landscape.

Nangs

The first time I saw a whipped cream canister, a schoolteacher whose name I do not remember was attaching one to a paper plane loosely looped to a string which was strung from one end of the room to another, before he pierced the tail and sent the tethered jet shooting across the room to teach the class about propulsion…

Whipped cream canisters are an industrial-looking addition to the average chef’s kitchen. Filled with pressurized nitrous oxide gas, they are a common cooking item used in conjunction with special nozzle-tipped canisters to combine pressurized gas into a liquid to create aeration in the liquid.

In short, they make bubbles.

The gas has also been used in dentistry for years, commonly called “laughing gas”, as a mild sedative painkiller – although its use appears to have fallen somewhat out of favour in recent years.

Many dentists will still offer it, supplied mixed with oxygen through a nose-piece, especially to children for conscious sedation. However, a raft of reasons from cost to safety have contributed to less dentists adopting it as a form of anaesthetic.

Nitrous oxide is also used, with some ridiculous infamy thanks to movies, as a fuel-booster for performance racing. It is introduced to the fuel mix to increase the rate of combustion and give an engine a power-boost (although car-enthusiasts are quick to point out that it does not work as portrayed in the Fast and the Furious franchise, to some racers’ disappointment).

This versatile gas even helps fuel rockets into space.

The next time I recall seeing a whipped cream canister, I was 14 years old and being encouraged to inhale the contents through a glass soda-maker to get high…

Nitrous oxide when inhaled acts as a dissociative and euphoriant, giving users a brief and powerful hallucinatory experience that can be timed to within five minutes on average.

In reality, part of this effect is caused by your brain being suddenly and violently starved of an oxygen supply.

When using nitrous oxide filled whipped cream canisters, there is a distinctive pop-and-hiss sound as the contents rush out of the little grey canister, and then as the gas is inhaled from a second medium – usually a balloon or whipped cream canister.

It is fairly normal for a user to lose motor control and hallucinate fractal shapes.

People fall down.

They laugh and talk gibberish.

They freak out and try to breathe normally again.

And then the rush of oxygen deprivation to your brain passes and the user is left in a fragile bubble for a few minutes until they return to a normal baseline.

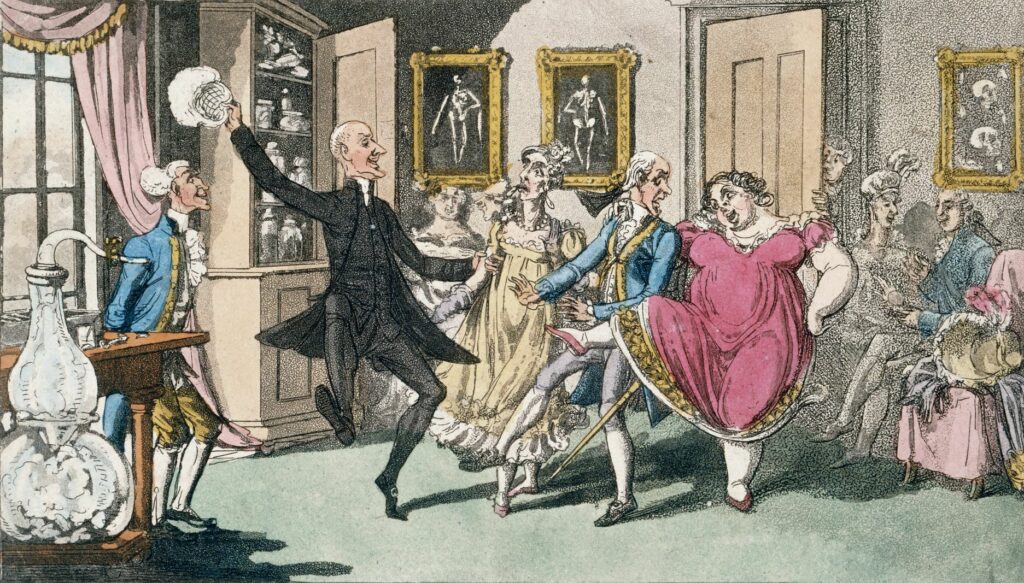

Nitrous oxide has been used recreationally since the 18th century when aristocrats began holding “laughing gas parties”. It remained the domain of aristocracy until its use in medicine became more common.

Now a fixture of the party-drug scene, they have earned countless monikers, although the most universally recognized in Australia are “nangs”, “bulbs”, and less frequently “whip-its”.

The etymology of the word “nangs” is somewhat mysterious, appearing to be derived from the dulled noise of human speech when under the effect of the drug. It seems to have entered the vernacular somewhere relatively recently and spread organically through younger users.

Previous to approximately 2000, the most common slang-name used was “bulbs”, named for the canisters its stored in.

Trends in the recreational use of nitrous oxide appear to have been on an upwards trajectory for a number of years, although figures on recreational use are incomplete at best, owing to the drug’s easy availability and grey-area legality.

According to information from the Australian based Alcohol and Drug Foundation, 36% of ecstasy users also used nitrous oxide recreationally in 2016, up from 26% in 2015 – Current anecdotal evidence suggests that trend can only be increasing.

Nitrous oxide carries a number of health and safety risks, and there have been recorded deaths from its use. The short-term risks include the sudden and rapid expulsion of freezing gas from the canister, which can cause frostbite-like injuries to the face, hands, mouth, and throat.

Additionally, inhalation of the drug has been proven to cause dangerous or even fatal responses such as hypoxia or the frightening possibility of exploded oxygen cylinders in some users.

After inhalation, and particularly during the initial seconds of the effect, injuries are common as users frequently lose touch with reality, and control of their motor functions. This is reportedly the cause of the tragic Schoolies death of teenager Hamish Bidgood in 2018, who plummeted from a Surfer’s Paradise balcony after ingesting nitrous oxide and alcohol.

If this is beginning to sound less than completely fun, consider the long-term health effects which doctors have begun discovering with some alarm:

In December 1993 a research article was published by Dr Teresa Flippo and Dr Walter D. Holder Jr discussing neurological degeneration due to B12 deficiency resulting from long-term use of nitrous oxide.

In October 2017, ABC News in Australia published an article discussing the dangerous rise in hospital admissions for nitrous oxide use in which Director of the Poisons Information Centre at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Dr John Dawson, said:

“Very recently I had a 20-year-old patient whose brain appeared to have the same level of damage as an alcoholic who had been drinking for 40 years.”

The article also discussed a patient’s inability to walk. [1]

However, the drug is still considered low-risk, with a non-existent addiction profile and no real expectation of the gas replacing harder street drugs.

Senior lecturer at Edith Cowan University was quoted as saying:

“The use of nangs has a low potential of harm, provided harm reduction strategies are used…

People do tend to have more than one ‘nang’, but are able to limit themselves given that it is often seen as a ‘kiddies’ drug and one would not spend copious amounts of money required to develop dependence.” [2]

Deaths are rare, with only three recorded in Australia since 2010, and records of severe neurological or respiratory damage are similarly anomalous. Despite the potential for harm, the risks are statistically very low.

Without significant public pressure or danger, there has simply been no need to legislate broadly to prevent its recreational use.

The accessibility of the chemical remains one of the biggest hurdles to preventing recreational use – It is legal to purchase for the purposes of cooking and baking, with restrictions only applying to the sale of nitrous oxide for inhalation and drug-misuse.

South Australia has taken the strongest approach to limiting the drug’s misuse, passing strict new legislation regarding the sale and advertising of nitrous oxide. The new regulations, passed in 2020, include a restriction on selling or supplying whipped cream canisters to people under the age of 18; and a restriction on sale of the product between 10pm and 5am.

Why a restriction on sale between 10pm and 5am?

This appears to be a measure to control the illicit trade in late-night “nangs” for urban nitrous enthusiasts.

As a result of this restriction, dozens of companies have cropped up in almost any city you’d care to look, each with variously suspicious sounding names, and each specializing in “cooking” or “party” supplies; primarily different brands or offerings of nitrous oxide:

In Brisbane there is Whip It Good (“Whippin’ Since ‘18”), Nan’s Nangs, and Nangaroo (which has its own app in the App Store).

In Melbourne there is the innocuously-named Cake Emergency, Nangstar (providing an ETA of 15-60 minutes and 24 hour service), and NangMe (which was offering a 27 minute average delivery time on its website and offers live-chat support).

Most large cities in Australia have a similar service on offer.

Each of the aforementioned companies offer barely-concealed disclaimers on their websites stating that their products are ‘not for human consumption’, and there are no directions to actually consume the products anywhere in sight.

No other safety or health precautions are taken, and none are required by any legislation. It is simply up to the customer to use the product appropriately and not misuse it in an unhealthy or illegal way.

However, the drug-specific terminology, “nangs”, so readily used in the advertising suggests that these companies are giving a knowing wink to their customers and are likely not expecting to cater to a significant demographic of late-night cake-decorators.

Ultimately, availability of these products has never been a significant barrier to their use. Teenagers have long been able to walk into most corner stores and buy a box of whipped cream bulbs. The retailer had very little power to prevent their sale, and very little interest in doing so.

Convenience seems to be the primary driver for the apparent success of these little companies selling a niche product with murky legality.

So “nangs” continue to proliferate youth drug culture and their ease of access continue to make them a popular fixture on the late-night party scene.

Their relative safety has contributed to their quiet proliferation and low number of deaths and hospitalizations.

Potentially millions of Australians have misused the drug, and self-reporting is historically unreliable.

Poppers

Another popular drug in the inhalant class that has come under scrutiny in recent years, due to safety concerns and its easy availability is amyl nitrite (or its cousins butyl, propyl, isopropyl, isobutyl, pentyl, isoamyl, octyl, and cyclohexyl nitrites) commonly sold and consumed under the name “poppers”.

Brought into medical use in the 19th century, amyl nitrite is used to treat heart diseases and angina, by inhaling the vapours to cause vasodilation and lower blood pressure.

Nitrites are unique among inhalants in that they have the effect of vasodilation and muscle relaxation, rather than effecting the central nervous system in wild and psychedelic ways, and so they are commonly used to enhance sexual activities – especially anal sex.

It is also used as a solvent in cleaning agents, including leather cleaner and tape head cleaner, although most legitimate cleaning products use safer solvents or only trace amounts of the nitrites. This has traditionally been used as a branding workaround in order to continue selling the product, frequently behind the counter at sex shops.

It is conveniently dispensed in small, brown, glass bottles with non-descriptive graphics and a label saying “Not for human consumption”.

The drug’s public popularity as a street drug came about in the 1960s and prominently in the 1970s, where a promiscuous sexual culture, the ever-convergent drug world, and a burgeoning club scene combined to create a near-legendary era of experimentation where erotic-enhancers like alkyl nitrites found themselves a comfortable home.

The drug’s usefulness in specifically enhancing anal sex seemingly cemented its place in gay culture. By the 80s it was almost de rigueur.

Using the drug is easy – Due to the liquid’s low boiling point, the product vaporizes on contact with oxygen, and the vapours when inhaled produce the effect of softening the smooth muscles of the body, including blood vessel walls and the anal sphincter.

A user simply takes the lid off the bottle and inhales deeply through the nostrils.

Nitrites are also frequently misused in dangerous polydrug combinations alongside stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine. Their availability was divided into two forms: legally obtained medication from websites, or products labelled as cleaning products and sold somewhat-illicitly in sex shops.

The safety profile of alkyl nitrites is somewhat confused for consumers, with stories of everything from sudden asphyxiation to blindness being reported. In fact, the safety data for alkyl nitrites collectively is incomplete at best, with much confusion stemming from characteristics identified in specific higher-risk variants, but when used with caution most users experience only mild ill-effects.

Isopropyl nitrite is a relatively recent addition to the recreational nitrite family, and its spread through unscrupulous producers and backyard manufacturers (because where you find prohibited drugs, you will find home-producers) has meant that it has become widely available without consumers being fully aware of the risks, or even the difference between products.

Isopropyl is considered among the least desirable and most toxic variant of “poppers” available and has been linked to a rare but very real risk of maculopathy – loss of vision. Users sometimes report vision disturbances such as glowing spots in their field of vision which can persist for days to weeks, and in some severe cases can become long-term or permanent injuries.

This version of the drug has recently been banned in Australia, but that may not defeat its presence in the country.

No responsible proponent would call even the lower risk forms of the drug harmless or inherently safe. According to the aforementioned Alcohol and Drug Foundation, the list of harms associated with alkyl nitrite use is reasonably long and varied:

The liquid is corrosive and can cause skin burns, and the vapours can cause irritation to the skin around the mouth and nose.

Swallowing the liquid carries a risk of asphyxiation as the throat swells and begins to close.

As with any inhalant, there are respiratory risks, as well as the addition of cardiovascular damage due to such severe vasodilation.

There are also carcinogenic concerns, particularly where cyclohexyl nitrite is used, and risks of neurological impairment.

There is an ongoing risk associated with B12 depletion; that is, a complex-sounding ailment called methemoglobinemia, which deprives the brain of oxygen and essentially leaves a person hypoxic – a life-threatening condition.

There is also a significant polydrug use component to the risks of the drug…

Drugs in general encourage a loss of inhibition in the users. This creates a cycle of thinking that encourages drug users to take other drugs, including drugs they are unfamiliar with, to sustain or increase the high.

Alkyl nitrites, due to their short-lived effects, encourage rapid multi-drug use to sustain the length of the high and ward off the headaches which are a common side-effect of vasodilation and rapid changes in blood pressure. These blood pressure changes also contribute to risks when combining the drug with Viagra or alcohol, both of which are commonly available in the clubbing scene. [3]

There is an additional risk factor that is somewhat less quantifiable, but anecdotally appears to have been of significant note. That is, the loss of inhibition experienced when using nitrites recreationally often extends to sexual activity, as many users report the drug makes them aroused and primed for sex.

The resulting risk-taking behaviour is regarded as one of the major harms borne from the proliferation of alkyl nitrites in the gay community, particularly – and to devastating effect – at the height of the AIDS Epidemic in the late 80s.

And then there are the deaths, relatively rare though they are, which undermine public support for this facet of queer culture so distinctly and garner unwanted interest from outside the affected communities – much to the detriment of the communities grieving their losses.

Nitrites have historically enjoyed, at best, sketchy legality in Australia…

There has never been a nitrite product registered for therapeutic use in Australia. The product has traditionally been sold in a largely unregulated fashion through sex shops and similar off-radar establishments in the form of “leather cleaner”.

However, in response to growing community concern, or at least the appearance of it in the media, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Association recently proposed changes to the Australian Poisons Standards listing all alkyl nitrites as Schedule 9 drugs, alongside heroin and cocaine. This would make it a crime to be in possession of any version of the drug.

Ultimately, after community backlash, several softer changes were enacted, shifting amyl nitrite to Schedule 3 (Pharmacist Only medication), and banning two of the more dangerous variants outright.

…Therein lies the rub.

As mentioned, there has never been a nitrite product registered for therapeutic use in Australia. Without a registered product, pharmacies do not yet stock a product to fill the gap.

Further complicating supply is the change to legality which leaves retailers unable to sell the product in the grey-market manner as before.

This has left users in the gay community, who feel this product provides a safe means of reducing potential harm and increasing basic enjoyment of sex, confused as to how to continue accessing a supply of the product, which many argue has significant health and safety benefits for responsible users seeking to avoid sexual injury.

There remains one legal workaround, until the medical manufacturing industry catches up with demand, and that is to obtain a legal prescription and search for a legal overseas supplier who will provide a copy of your prescription for you with your order, should Customs take issue with your attempt to import a prohibited drug. However, this is not standard practice for the online-marketplace industry, and it is unlikely this is a reliable solution at this moment.

Detractors of the prohibitions against poppers believed the measures proposed by the TGA added to the alienation of users – particularly in the queer community; and created an inherent risk of propagating an unregulated illegal trade.

Jarryd Bartle, criminal law lecturer at RMIT and former candidate for Melbourne-based political group the Reason Party, said:

“All drugs carry health risks…

We know that a prohibitionist approach to any drugs increases the amount of harm associated with those substances, particularly if you’re criminalizing possession.” [4]

One of the risks is the availability of unregulated products from the foreign market, where nitrites are sold freely. Particular variants, including the aforementioned isopropyl nitrite, are now legally banned here for sale or importation. However, these variants are commonly available overseas and through unscrupulous manufacturers.

With prohibitions in place and no legal market ready to fill the gap, users run increasing likelihood of seeking their supply through black-market imports, exposing them to a greater chance of purchasing these more dangerous products unawares.

Detractors are also concerned about the heightened risk of closeted gay men feeling too embarrassed to talk to a doctor and ask for the medication legally, opening them to a risk of shoddy practices by more anonymity-focused sellers.

Shoddy practices already exist, of course, and there are already delivery services that effectively skirt the law throughout Australia’s large cities. Again, as with Nangs, the company names are not subtle, with clear indicators as to what the businesses trade in. Pragmatically-titled companies like Buy Poppers By Post sit alongside euphemistic names like AmylNitriteRoomOderizers.com and more direct titles like Love Poppers. Each of these offers a similar model to the nitrous-dealers above.

However, where each of these companies offers one-off services, there are also companies emerging that offer subscription packages, from companies like His Popper and Poppr.

Some of the subscription packages offered surpass any safe usage expectations, offering in one case four bottles a month delivered. This firmly places the user in the high-risk category for nitrite use. There appears to be no safe way to consume four bottles of amyl nitrite a month without encountering significant health issues in fairly short order. Risks at that level of consumption include severe neurological impairment from hypoxia.

These companies flout laws in more direct ways, by offering discreet postage and simply circumventing Australian Customs and Border Control checks with creative packaging or by using local/interstate postage where less scrutiny exists.

Essentially, customers who purchase this way take the same risks as somebody purchasing designer drugs from the internet.

These risks above are not commensurate to the harms of the drug, and there is an argument against any form of criminalization where it would increase the dangers of the drug’s presence in the community.

However, as of October 2020 with the last amendments to the Poisons Standards, the drug remains within some reach of its market and its safety has potentially been bolstered for a likely majority of users who may still happily adopt these health measures without fear of stigmatization.

These half-measures are characteristic of an approach to drugs in Australia that can so often be described as reactionary and over-cautious.

Conclusion

There are variations on a theme; cheap drugs available easily that, due to their relative safety or low economic viability, do not warrant significant attention outside the narrow articles of local newspapers.

Inhalants constitute a class of drugs that have, by virtue of their wide availability, escaped the scrutiny of their harder, more nefarious narcotic cousins.

Street-level-or-lower drugs continue to exist because banning the components has become impossible.

The genie is long since out of the bottle, and he’s developed a taste for getting fucked up.

Inhalants have earned a low-rent place in the drug hierarchy, with chroming and glue-sniffing remaining the basal low of getting high. The absolute abyss of the hierarchy are reports of poverty-stricken East African psychonauts huffing fermented sewage to produce a high – a perfectly horrid concoction called “jenkem”.

Even at the most white-collar end of the spectrum, there are cheap and nasty ways to get high. DIY hacks like huffing Dust-Off computer cleaner to get a hypoxic buzz became a notorious public-interest story that circulated in schools with horrific, unverifiable stories about parents finding their children dead in their beds.

However the appeal of children trying it was always incredibly limited in a world where it’s really not that difficult to buy cannabis.

Nitrous oxide – “nangs” – may provoke a similarly low-rent image, and that may be somewhat fair as its medical efficacy is low and the primary abusers of the drug are low-income and underage users.

The drug, however, shows a significantly safer history of use than most drugs of the inhalant class. Its prohibition is largely a preventative measure to further harm. With that said – self-regulation by users appears to have a greater effect on limiting harm from usage.

The drug remains widely available and broadly misused with minimum harm to the community; and no notable long-term health effects on what would be deemed ‘normal’ usage rates. Again, rare cases of dramatic overuse appear to be the strongest indicators for negative long-term health effects.

It’s medical usage, while rendered nearly obsolete at this point, remains valid and its use in paediatric dentistry undermines the warnings of the drug’s dangers somewhat.

But nothing is helped by the various other homes that nitrous has found, where the most harmless and naïve neighbours are stoned teenagers, and the worst house on the street is where speed-users huff nitrous to ease the comedown from long stimulant binges.

There is no clean and acceptable image to find solace in; at best there is a YouTube video of clowns falling over.

Alkyl nitrites, or “poppers”, present a somewhat more complex challenge. While the method they have traditionally been bought, sourced, and consumed suggests an under-the-counter drug with nil medical efficacy, it is in fact a class of medically sound treatments for serious ailments that carry reasonable safety profiles and can be safely administered by a patient on an as-needed basis.

While it can still be legally obtained, technically speaking, the new restrictions on its sale will likely drive a greater number of users to less reliable, illegal suppliers and force the product underground to scrap with the nangs and paint-rags.

Further – It may be impossible to legislate a drug without stigmatizing it.

Legislating this specifically for products that have everyday household, industrial, and particularly medical uses invites a broader discussion about legislating items that have the potential for misuse generally – a slippery-slope Australian legislators already have a difficult time navigating.

People exert enormous creativity to meet their needs, and indeed to get high.

Legislating against the innovation of human endeavour is a losing bet in most circumstances, and the hypocrisy of choosing one product and not another (where alcohol and tobacco would be obvious candidates) undermines the sincerity of the Australian Government’s message at all.

Users who feel persecuted seem unlikely to acquiesce to the whims of legislators and wowsers, and where they cannot ably fulfil their needs through legal means, humans have proven time and time again that they will find an alternative solution.

With providers already lining up to give people what they want in a barely-regulated web-sphere, it may be time for Australian legislators to engage in a deeper discussion about the practicalities, rather than the ideals, of drug prohibition laws in a marketplace that barely cares.

References

[1] – Doctors warn of dangerous rise in use of ‘nangs’ – ABC News

[2] – Nangs scare campaign a gasbag: experts on nitrous oxide (thenewdaily.com.au)

[3] – Amyl Nitrite – Alcohol and Drug Foundation (adf.org.au)

[4] – The bid to ban ‘poppers’: public health necessity or an act of discrimination? (smh.com.au)