Debbie Behan Garrett is an African American doll expert, author and collector who has been a passionate advocate for black dolls of all types – their history, their cultural importance and their conservation – for over 20 years!

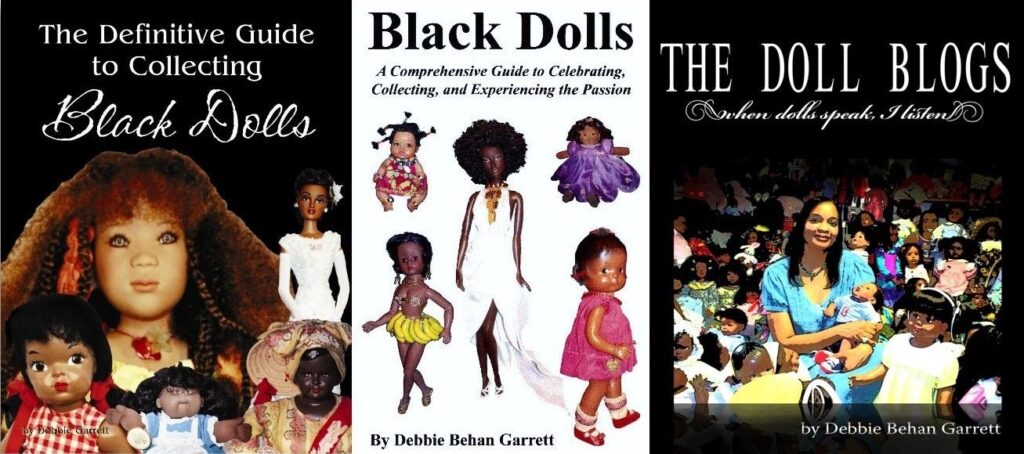

A giant in her field, Debbie has also published 3 books about black dolls: ‘The Definitive Guide to Collecting Black Dolls’ (2003); ‘Black Dolls a Comprehensive Guide to Celebrating, Collecting, and Experiencing the Passion’ (2008); and ‘The Doll Blogs: When Dolls Speak I Listen’ (2010, revised in 2022).

In addition to her books, Debbie also runs ‘DeeBeeGee’s Virtual Black Doll Museum’; along with the ‘Black Doll Collecting’ and ‘Ebony-Essence of Dolls in Black’ websites. Vehicles Debbie uses to share her passion and knowledge with others, in the readily accessible online medium.

Rounding out her many skills, Debbie also engages in doll making and repair; whilst also working as a freelance writer and editor. Making her a truly impressive and talented woman indeed!

We at The Aither were drawn to Debbie and her expertise as we love toys of all types – especially dolls. They are perfect art objects and also exist as historical items that can shine a light on the times, and cultures in which they were made.

With that in mind, Debbie’s interest and expertise in black dolls is a record not only of the many talented individuals and companies who made the dolls, but also of global human history and culture. Our many achievements, our fallibility; and our ever evolving attitudes to race.

Wanting to learn more about Debbie and black dolls, we sent her some questions to answer over email.

Check it all out, below…

Getting Acquainted

City, State and Country you currently call home?

Southwest region of the United States.

Personal motto(s)?

“Do it with integrity and style as though my reputation depends on it.”

What role did toys play in your childhood?

Toys played a significant role in my childhood.

They allowed me to use my imagination to create a happy place where all was well in my world.

If you could live in any place, during any historical era – Where and when would that be?

…and why would you choose that time and place?

I’d live in Africa during the 14th to 15th century before European invasion when African civilizations, such as Mali, flourished.

I’d be part of the royal Keita family that ruled Mali in the 14th century. This would take me back to my “royal” ancestral African roots.

Doll & Collecting Questions

When and why did you first become interested in collecting generally, and black dolls specifically?

… and any pivotal collecting moments / influences?

Dating back to my preteens, I began collecting stamps after becoming a pen pal at age 11 with a girl from Norway. I kept the canceled stamps that were on her letters.

My mother also saved interesting stamps from mail she received.

My interest in black dolls began after the birth of my daughter in the late 1970s. I wanted to ensure that she owned black dolls as a child to reverse/correct the fact that all my childhood dolls were white. I wanted my daughter to see positive images of herself in her dolls.

Toward the end of my daughter’s doll-playing years, I begin collecting black dolls.

My first black doll had been a planned gift for my daughter. Instead of giving it to her for her 13th birthday, I kept the doll for myself, which began my quest to fill the void of not owning black dolls as a child.

For our readers at home who may be unaware – Please outline the various changes in style, use and manufacture of black dolls in America, since modernity; so, post 1760s and the Industrial Revolution.

• 1700s: Some of the earliest black dolls in America date back to the Antebellum South.

These were handmade dolls using rags, cornhusks, found materials, and other household and environmental items. Handmade by enslaved women for their children and/or for their enslavers’ children, the double-sided doll, later known as Topsy Turvy, is two dolls in one: a black doll on one side and a white doll on the other. These legless dolls share a body with one doll completely hidden below the shared full-length skirt. Flipping the skirt over one doll’s head reveals the hidden head and torso of the other doll.

• 1800s: Early mass-produced dolls that date back to the 1800s were often stereotypical caricatures intended to strip Black people of their humanity.

These dolls had the deepest complexions (truly black, never brown) with bulging eyes, and oversized lips that were usually red. Made for the enjoyment of white people and to belittle those the dolls were supposed to represent, Black people did not buy these inappropriate dolls for their children. Mammies, butlers, and other dolls representing servants were also marketed during this period and for many decades beyond.

• 1850s: Dolls representing the character, Topsy, from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly (1852) portray what white America during the Jim Crow era termed a female picaninny – a Black child with multiple braids extending upward or a minimum of three braids – one braid on the top of the head and two on either side. With fewer braids or none at all, several doll companies continued using the Topsy name for black dolls well into the 1960s.

• 1901: Fashioned after the previously described double-sided handmade doll, the doll that was later patented in 1901 for mass production and named Topsy-Turvy by Albert Bruckner, is one example of an early mass-produced doll made for the American market.

The white doll was usually more elaborately dressed than the black doll that was typically dressed as a servant.

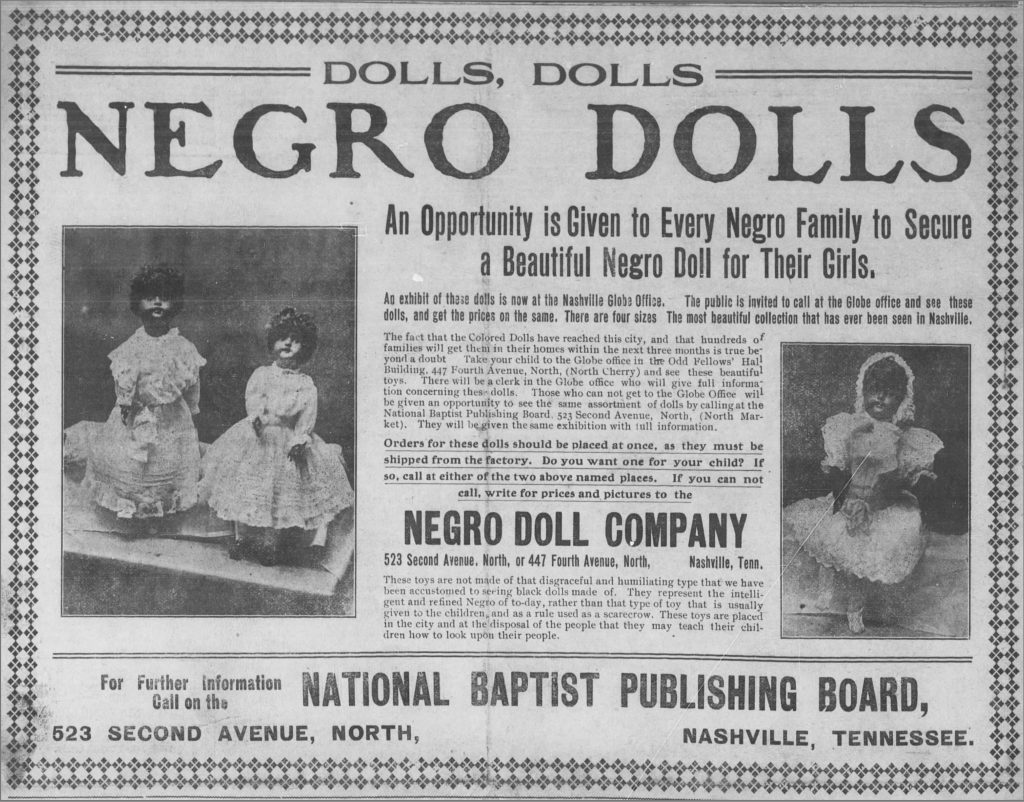

• 1911: R. H. Boyd, a former enslaved man, founded the National Negro Doll Company after he tried to purchase dolls for his children but could not find any that were not gross caricatures of African Americans.

Boyd was the first to market mass-produced black dolls to African American consumers.

• In 1919, the Negro Factories Corporation, a branch of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, founded by Marcus Garvey, generated income and provided jobs for Blacks with its numerous enterprises, one of which was a black-doll factory.

The goal of Garvey’s doll factory was to ensure that Black children had dolls that looked like them to play with and cuddle.

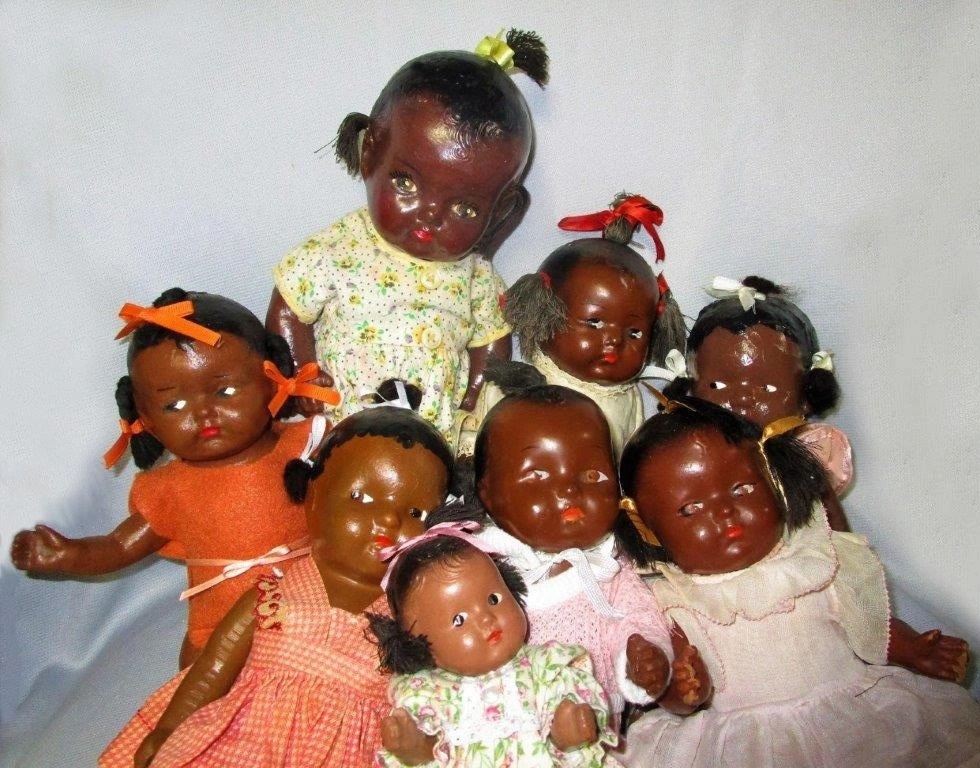

• Early 1900s-1950s: Manufactured dolls that were brown versions of their white counterparts emerged (white dolls painted brown). These dolls, unfortunately, were not readily available in the Southern, segregated regions of the United States with some stores refusing to stock them, preferring to stock the stereotypical dolls instead.

Where and when the brown versions of white dolls were available, they usually sold out first because fewer were made – the supply did not meet the demand for black dolls that portrayed a semblance of humanity (even if they had white features).

• From 1951-1953: The Ideal Toy Co. manufactured the Saralee Negro Doll, described as the first anthropologically correct black doll. Based on photographs of Black children, the doll was sculpted by Sheila Burlingame with the final approval of Sara Lee Creech, whose idea it was for a mass-produced ethnically correct black doll after seeing Black girls playing with white dolls and realizing that Black children should have dolls that reflect their image.

Other companies included black dolls in their product lines, but the practice of painting white dolls brown and creating these in fewer numbers continued for decades.

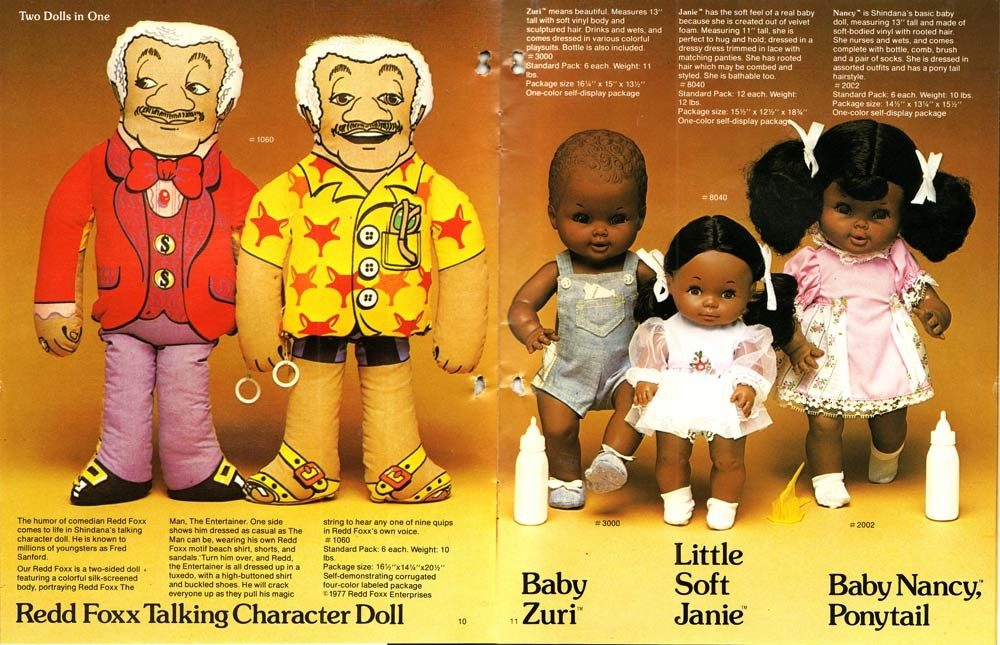

• 1968-1980s: Shindana Toys is the first American company to mass-produce black dolls with ethnically correct features. (R. H. Boyd’s dolls were imported from Germany and were earlier versions of white dolls “colored”/painted brown.)

Shindana’s line of dolls also included portrait dolls of Black celebrities, entertainers, and athletes.

• 1980: Twenty-one years after Barbie debuted, Mattel released the first Black Barbie, the first black doll to use the Barbie name. Before 1979/1980 Christie was Barbie’s Black friend.

Francie was her “Colored” cousin that did not survive shelf longevity after pearl-clutching non-Black consumers complained that a doll relative of Barbie was black.

• 1980s-present: Black dolls have evolved from stereotypical caricatures to more appropriate representations of Black people. Major doll manufacturers began meeting consumers’ demand for doll lines that represent people from all walks of life (skin colors, conditions, traits, hair colors, textures, etc.).

Most toy shelves and online doll-buying sources are no longer chiefly dominated by blonde-haired, blue-eyed dolls. There are now dolls for everyone.

• Since the late 1980s/early 1990s: An increasing number of doll artists offer black dolls specifically or incorporate them into their doll art for adult doll connoisseurs to collect.

Was there much of a difference between American black dolls produced in the North, compared to the South, prior to the end of the Jim Crow Era?

… and can you please outline these differences, and the reasons for them?

Prior to the end of the Jim Crow era, most American black doll production by major doll companies (E. I. Horsman, Effanbee, Madame Alexander, and Vogue) was done in the northern states and chiefly in New York, with Vogue dolls being produced in a cottage industry in Massachusetts.

The black stereotypical dolls during this time were most likely made and sold mostly in Southern states. Some were used in product advertising.

The lack of suitable black dolls for my mother to buy for me during my childhood was based on southern stores refusing (or their reluctance) to stock the more appropriate black dolls made by the major doll companies mentioned above.

If you had to choose 1, what would you say is the greatest mass-produced black doll of all time?

… and why does it reign supreme, in your opinion?

It is difficult for me to choose the greatest mass-produced black doll of all time.

There are those that are highly sought after by collectors, but I’m not sure any of these would fall into the greatest category.

Popular mass-produced black dolls include Madame Alexander’s three versions of a doll named Cynthia. It was made in three different sizes; 23 inches, 18 inches, and 15 inches for one year only in 1952. Collectors strive to acquire all three.

The Saralee Negro Doll because it is a forerunner as the first anthropologically correct mass-produced doll is another highly sought-after doll. The recent discovery that Ideal Corp. produced a limited number of Saralee’s siblings entices collectors to look for the doll’s siblings.

The entire Shindana catalog of dolls is popular among black-doll enthusiasts because this black-owned company was founded in the aftermath of the 1965 Watts (California) riots that erupted during a police brutality protest. The company’s goal was to rebuild the community through Operation Bootstrap businesses that employed community residents.

The Shindana Doll Factory was one of their businesses and the dolls, like no other, were positive representations of black children, adults, and celebrities – I guess for me, it is Shindana’s catalog of dolls.

What can you share with us about black dolls from countries / continents other than America?

Such as Australia, The African Continent, Britain (England, Ireland & Wales), Europe (France, Germany etc), Asia (China, Japan, Korea), The Indian Subcontinent (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka); etc.

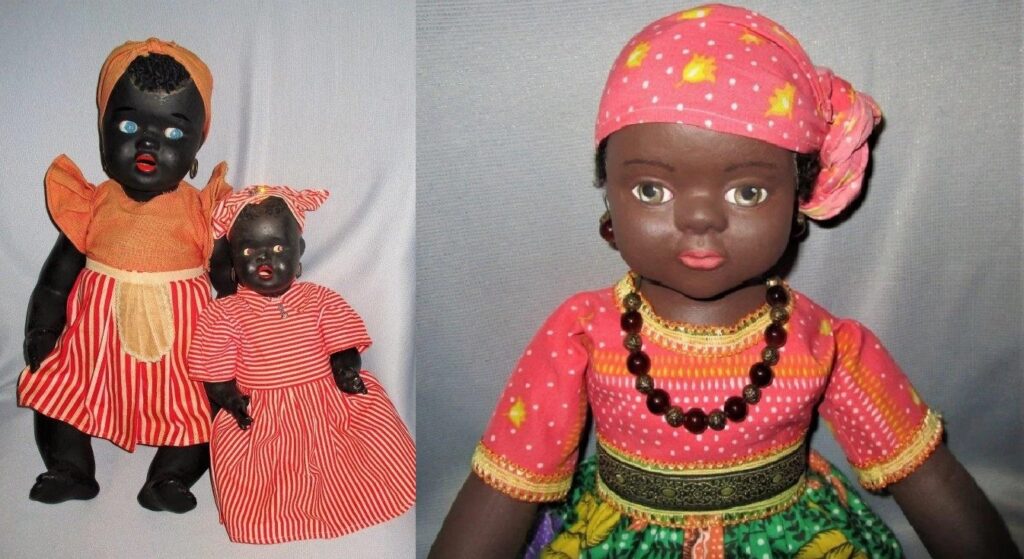

Black dolls made outside U. S. borders have typically been better representations of Black people. This is not to say that none were misrepresentations (the Golliwog, for example).

Antique French and German black and brown dolls often used the same molds as white dolls; however, many companies created dolls with ethnically correct facial features decades before this was practiced in the States.

In England, the Pedigree doll line and others included included ebony-complexioned black dolls in their lines and referred to the dolls as African. These often had ethnically correct or even slightly exaggerated facial features. Some of Pedigree’s lighter brown dolls were referred to as “dusky” in color.

Some countries (Germany being one) dressed their black dolls in tribal attire of grass skirts, beaded necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and other items they imagined an African would wear.

Early black dolls made in Asia typically were stereotypical caricatures with ebony complexions and exaggerated facial features.

Dolls made in Africa in the past typically were used in tribal rituals such as to promote fertility or to replace a child that died at birth or shortly afterward. There remains a scarcity of black play dolls in Africa today which has prompted some entrepreneurs to create and market black dolls to encourage African girls to see themselves in their playthings.

In the modern doll market are dolls that represent Native Australians made by Australian doll companies (such as Metti / Netta) and doll artists. For the tourist trade in other countries, dolls exist that represent brown-skinned first nations or indigenous people like the Maori people of New Zealand.

Contemporary black dolls made in Europe including the UK and in other countries are more appropriate representations of black people; however, white dolls remain more plentiful and some doll lines still exclude black dolls and other dolls of color in countries outside the U. S.

Aside from black dolls and related objects; what else do you currently collect?

…and what is it about those objects that so interests you?

After the birth of my children, I began collecting Black Santas, nutcrackers, angels, and ornaments to help the children develop their cultural identity through positive Black image exposure – real or fantasy.

I also collect Black Heritage postage stamps because these honor individuals who have made an impact on society.

I have a small collection of antique-to-modern Black Americana (BA) ephemeral items that I purchased from an elderly White woman during the 1990s. It seems this woman collected a mixture of positive and negative images of Black people.

I expressed my displeasure to a collector of BA about how it negatively portrays Black people, and she shared her opinion that if we attempt to erase history, we will be doomed to repeat it. So, I incorporated the paper items into my collection, which I have not and will not add to.

I have also never displayed these mostly insulting items, which include magazines and advertisements that date back to the early 1900s that depict Black people in positions of servitude and use broken dialect for any associated captions or dialogue.

Paper dolls, post cards, greeting cards, and other items that portray Black people positively or negatively are included in the BA ephemeral items. An 1850s copy of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly and some Kornelia Kinks post cards are the only things I have removed from the shipping box of BA.

I sold some of the derogatory post cards and placed the others that I did not sell back in the box which remains stored away. The Stowe book (because of the chapter on Topsy) is kept with my Dolls with Books exhibition items.

I also have a small collection of children’s books that feature a black doll as the main character. These books are part of my Dolls with Books exhibition that has traveled to community museums, libraries, and schools.

What are the top 10 black dolls and / or related items in your collection?

Please also share with us what they are, and why you love them.

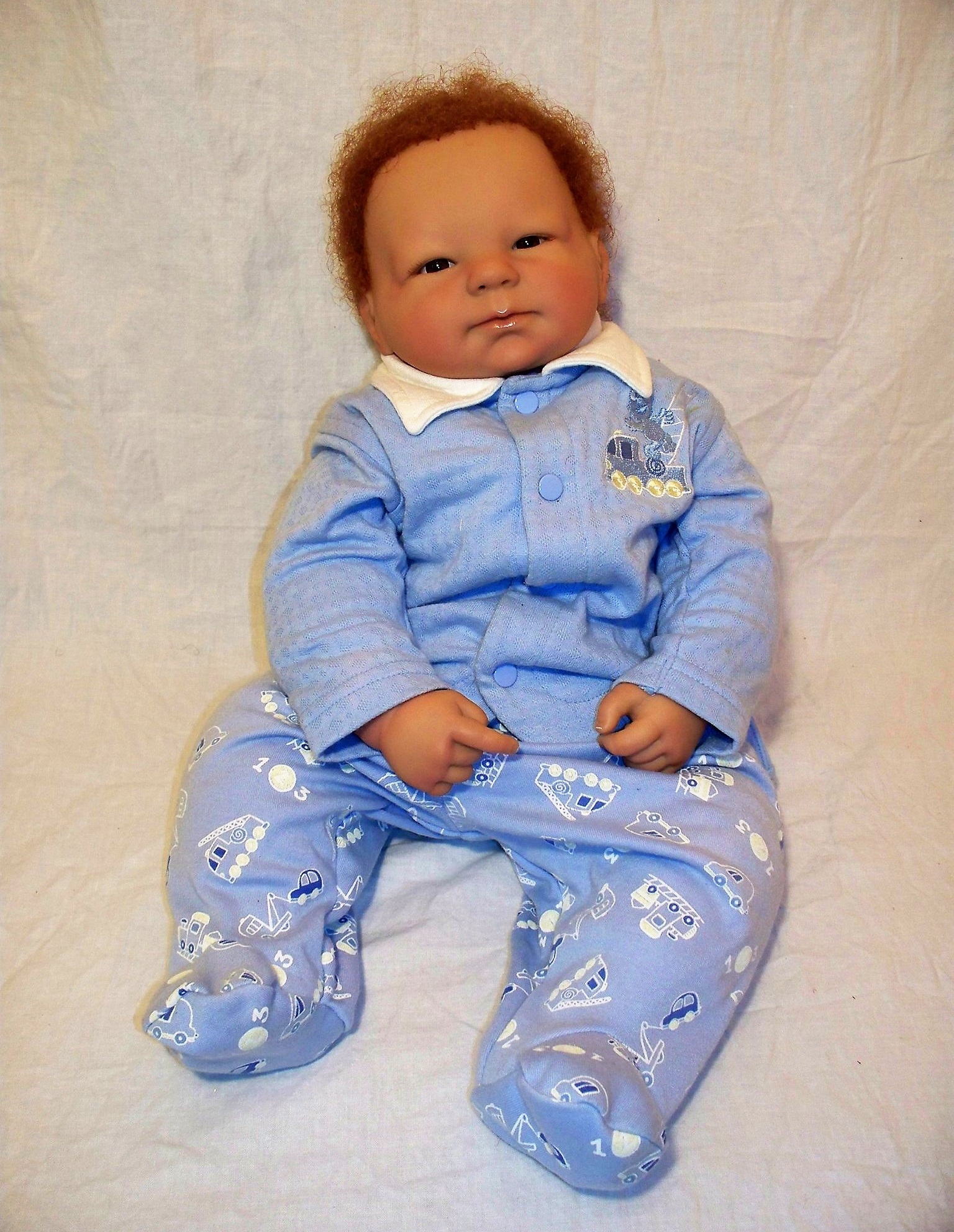

1. A portrait doll of my first grandson that captures his likeness as an infant.

The portrait doll was “reborn” using a doll kit by a former reborn doll artist who has left the doll-making world.

2 & 3. A portrait doll of my first grandson at age 7-1/2; along with a portrait doll of my second grandson at age 2-1/2.

Both were made in 2008 by master doll artist and sculptor Ping Lau. She used several photos of the boys taken from different angles to sculpt the dolls in their likeness.

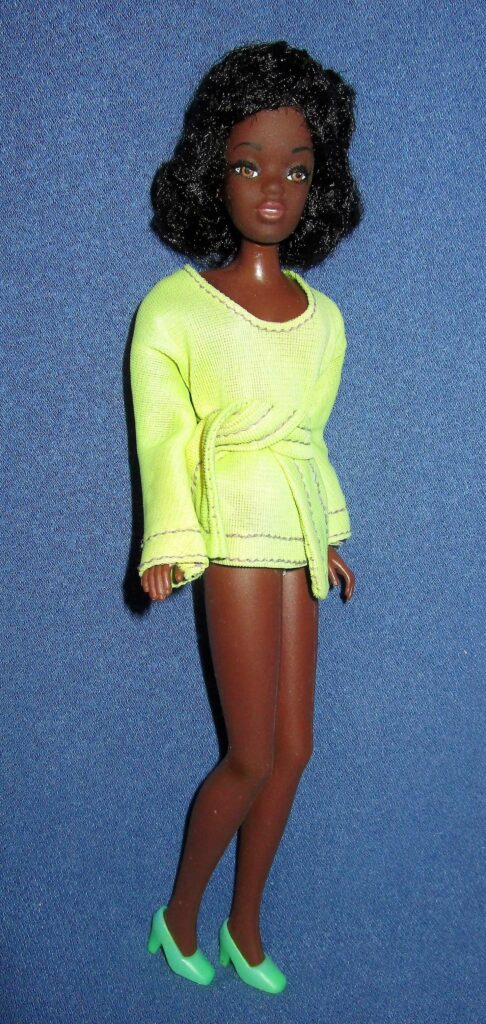

4. I cherish my entire Shindana doll collection, but their first fashion doll, Career Girl Wanda, is one of my favorite Shindana dolls.

5. One of my favorite dolls to collect is the Princess Tiana doll, based on Disney’s first animated Black Princess.. The Princess Tiana doll here was a Disney Store exclusive made in a limited edition of 4000. That doll is one of several Princess Tiana dolls in my collection and is one of my favorites.

The ornament was also sold through the Disney Store.

Both were gifts from a friend who knows that I collect Princess Tiana dolls.

6. Saralee Negro doll, the first anthropologically correct black doll made in the U.S. by a major doll company.

7. One-of-a-kind black dolls are among my favorite dolls to collect because no one else owns these.

8. Antique-to-modern dolls made in other countries that represent how black people were viewed by global toy and doll makers, specifically those made with ethnically correct facial features, are among my favorites.

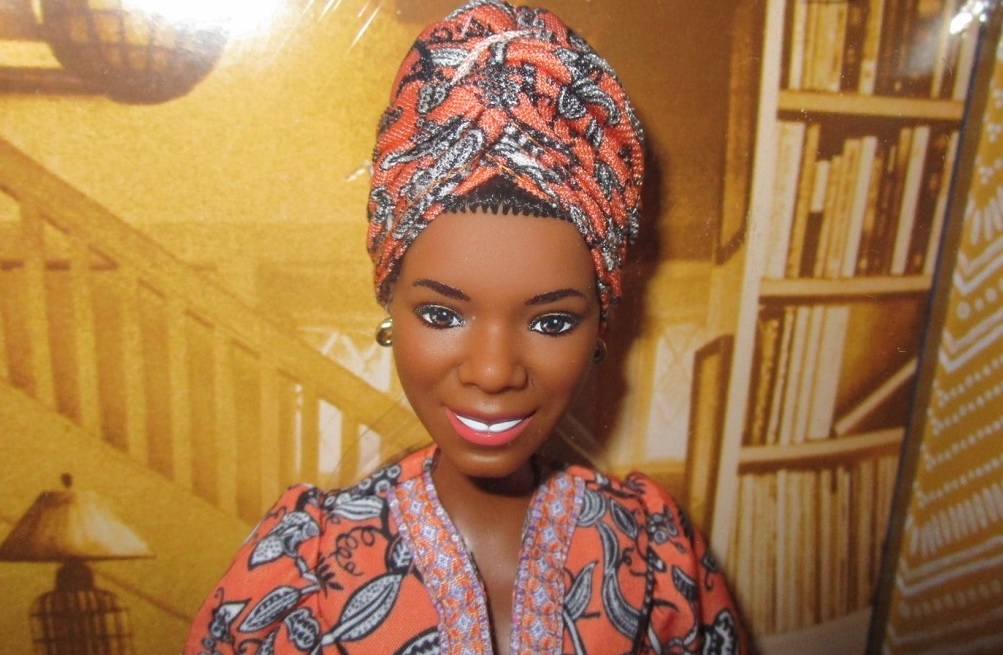

9. Celebrity dolls – Such as my Maya Angelou Barbie.

10. Black Barbie clones and competitors (during the early stages of adult-doll collecting, I despised Barbie, wanted nothing to do with the doll, and preferred 12-inch fashion dolls made by other companies instead).

What are your 3 favourite non-doll related items in your collection?

Please also share with us what they are, and why you love them.

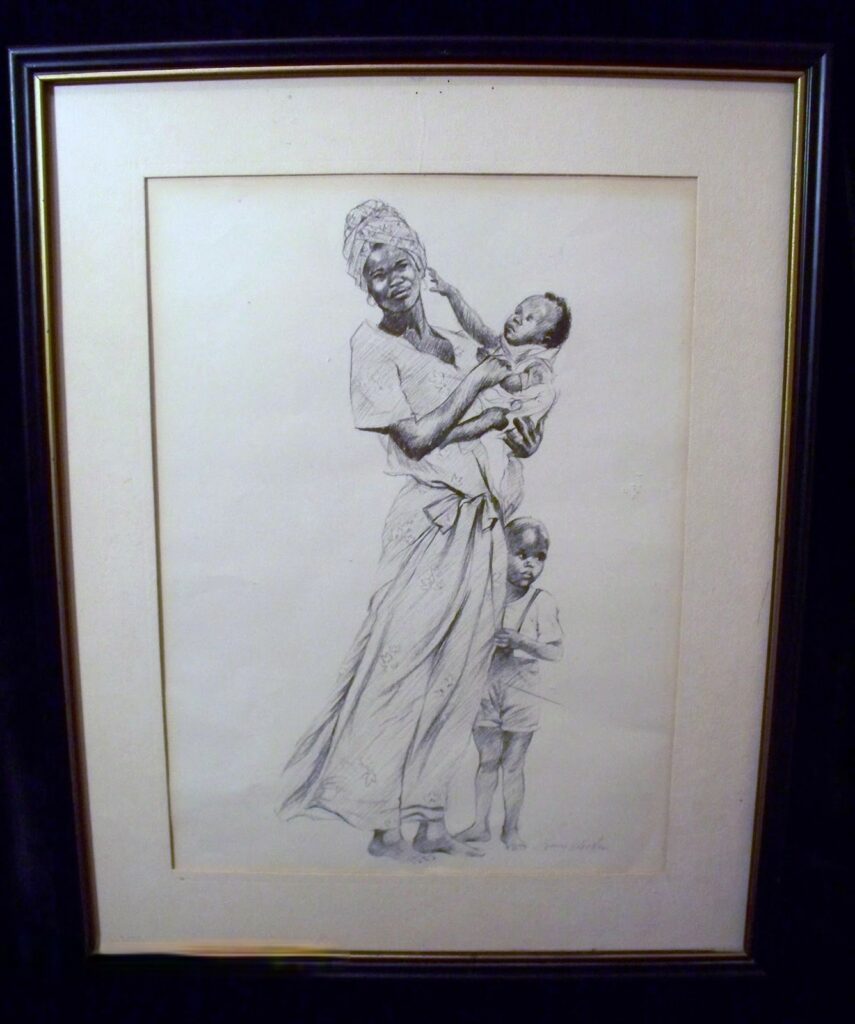

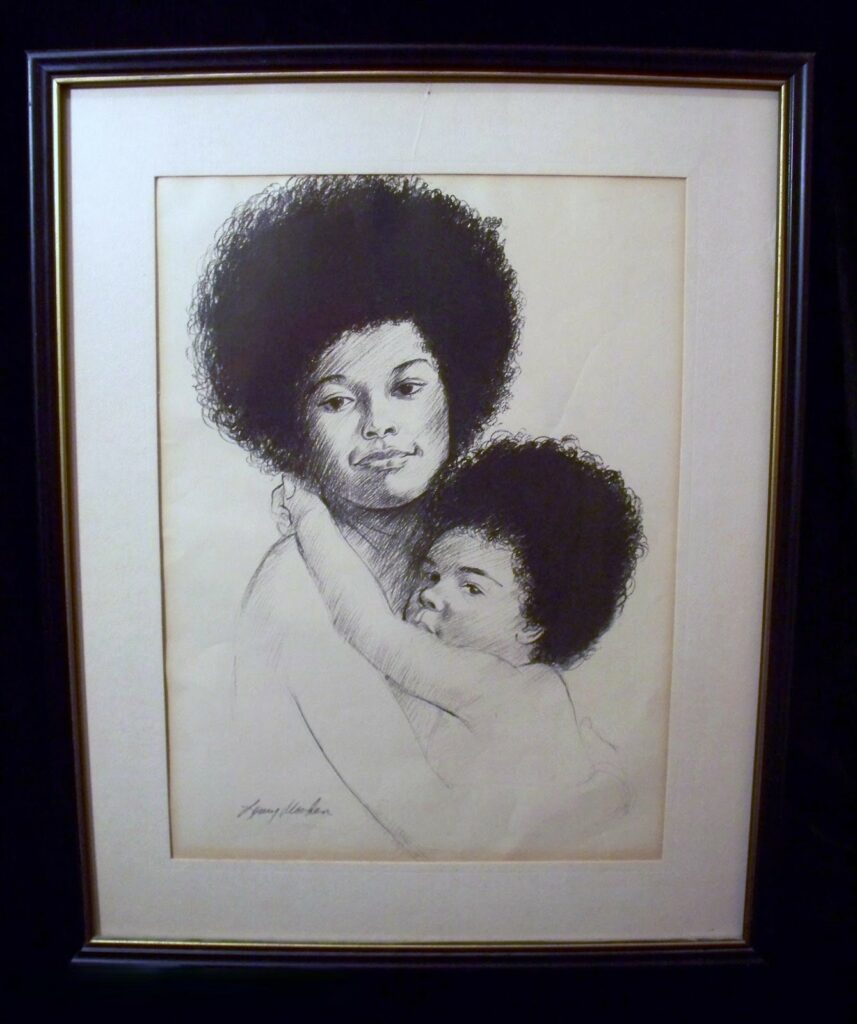

1. Artwork that positively depicts Black people, Black life and culture.

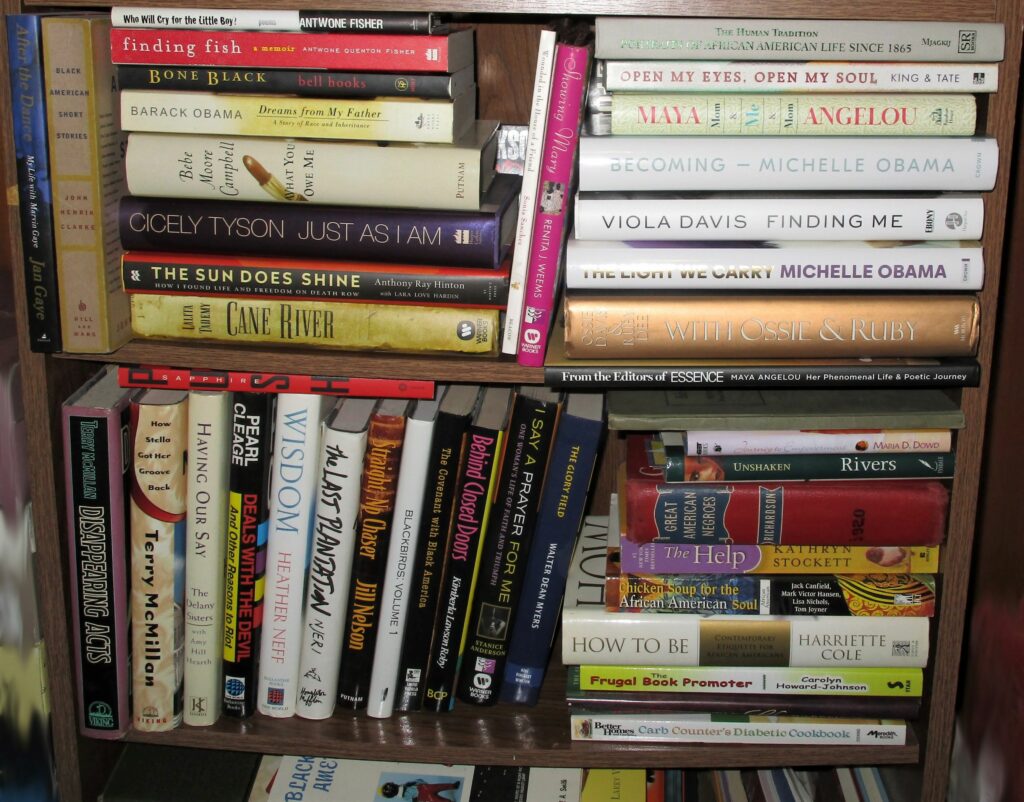

2. Books written by African American authors because I enjoy reading nonfiction and fiction books about Black life and culture.

3. Digital photos of Black children with black dolls.

(Most of these are Internet-captured photos and not originals. I am, therefore, not at liberty to include an example of one.)

If you had to explain your collecting and writing endeavors to some recently crash-landed aliens…

What would you tell them?

Black dolls renew my spirit. I enjoy seeing positive images of myself and people who look like me reflected in the dolls I collect.

To ensure that novice collectors have a reliable source of black-doll information, I began writing about and documenting the existence of past and present black dolls shortly after I began collecting.

Aside from Myla Perkins’ books (which were my black-doll bibles before I wrote my books), very few others consistently provide detailed black-doll information.

What advice would you give to someone looking to start collecting black dolls?

To someone looking to start collecting black dolls, I would advise them to purchase doll reference books, specifically the two written by Myla Perkins (‘Black Dolls 1820 to 1991 an Identification and Value Guide’, and ‘Black Dolls Book II an Identification and Value Guide’).

My books, which take off where Perkins left off in 1995, which are in no way as comprehensive as hers, also provide a source of black-doll information and entertainment: ‘The Definitive Guide to Collecting Black Dolls’ (2003); ‘Black Dolls a Comprehensive Guide to Celebrating, Collecting, and Experiencing the Passion’ (2008); and ‘The Doll Blogs: When Dolls Speak I Listen’ (2010 and revised in 2022).

I would further advise novice collectors to determine the type(s) of dolls that appeal to them and begin the collection with those. Beginners should also avoid buying dolls for their perceived future value because their value may or may not appreciate.

Joining black-doll clubs and other doll clubs where black dolls are valued both on and offline to network with and learn from other doll collectors is also advisable.

Whilst we know you through your doll related writing, curating, and collecting – Please share with us the details of your other creative endeavors… If any?

I dabble in doll restoration. Occasionally, if I purchase a preowned doll from a second-hand store (or from an online seller for a price I cannot refuse) I will restore it back to display quality. I’ve also done composition doll repair, but only for dolls that are part of my own collection.

I am not a doll artist, but I have made a line of cloth church dolls for friends, and I’ve sold a few of those.

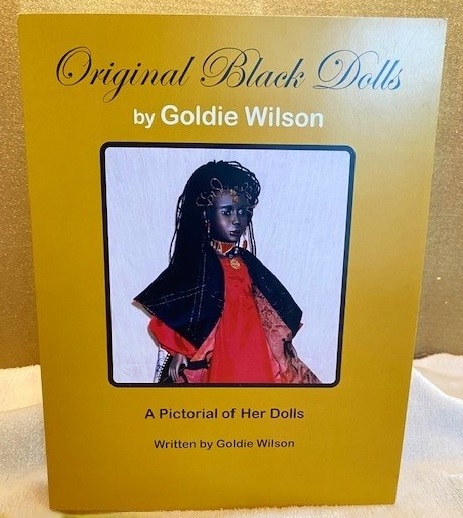

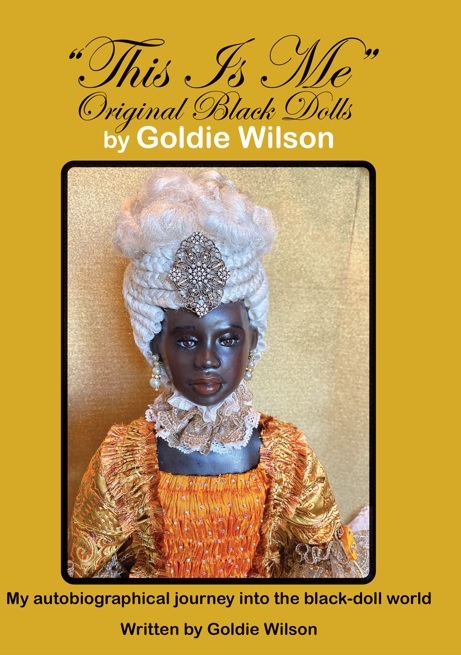

I recently edited and did the illustration layout for two self-published books written by Goldie Wilson, a renowned sculptor and artist of original black dolls. Her first book, ‘Original Black Dolls by Goldie Wilson a Pictorial of Her Dolls’ was published in 2021. Her second book, ‘“This is Me” Original Black Dolls by Goldie Wilson My Autographical Journey into the Black-Doll World’, was recently published in February of 2023.

For a nominal fee, I also provide black-doll identification and appraisals. My identification and appraisal services are outlined on Black Doll Identification and Values page of my Black Doll Collecting Blog.

In addition to my three books, I have contributed articles to a host of doll publications.

What are your aims and goals for the DeeBeeGee’s Virtual Black Doll Museum, which you established in 2021?

My aims and goals for DeeBeeGee’s Virtual Black Doll Museum are to:

1) Preserve black-doll history by curating and installing a minimum of 1000 antique-to-modern and one-of-a-kind (OOAK) historically-significant, non-stereotypical dolls in the museum.

(At the time of this interview, over 500 installations have been published.)

and;

2) To be a valuable source of black-doll information for our generation and for future generations via the website and other planned associated resources after the first 1000 installations have been published.

… and how can people at home get involved in the Museum?

People at home can get involved in the museum by sharing portrait-quality photos of, and information about, their antique-to-modern, OOAK, historically-significant, non-stereotypical black dolls that are unaltered from their original manufactured/created states.

There is a nominal fee for this which helps fund the mission of the museum.

Photo and doll information contributors are listed on the Patrons page of the museum.

Those who appreciate the mission of the museum can also donate any amount of currency using one of the donate buttons on the home page of the website.

Donations help defray administrative costs and annual website maintenance fees.

Readers should know that development and maintenance of the virtual museum and the other things I do in the doll world are fueled by my unwavering passion for black dolls and the documentation thereof. It would be wonderful if I received remuneration for doing these things, but I do not.

It is all done for the love of black dolls.

Did you manage to pass the collecting bug onto your children at all?

No, not at all.

If people wanted to check out your stuff, work with you or just have a chat – Where should they visit and how should they get in touch?

People can contact me through the contact links on website, my blogs, the museum, or by email at the following URLs and email address.

Links

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Website

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Email: blackdolls@sbcglobal.net

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Facebook

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Instagram

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Amazon Author Page

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Black Doll Identification & Appraisal Service

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Etsy Page

- Debbie Behan Garrett – Pinterest

- Black Doll Collecting – Blog

- The Ebony-Essence of Dolls in Black (Devoted to Doll Makers & Collectors) – Blog

- DeeBeeGee’s Virtual Black Doll Museum – Website

- DeeBeeGee’s Virtual Black Doll Museum – Instagram

All images provided by Debbie or sourced online.