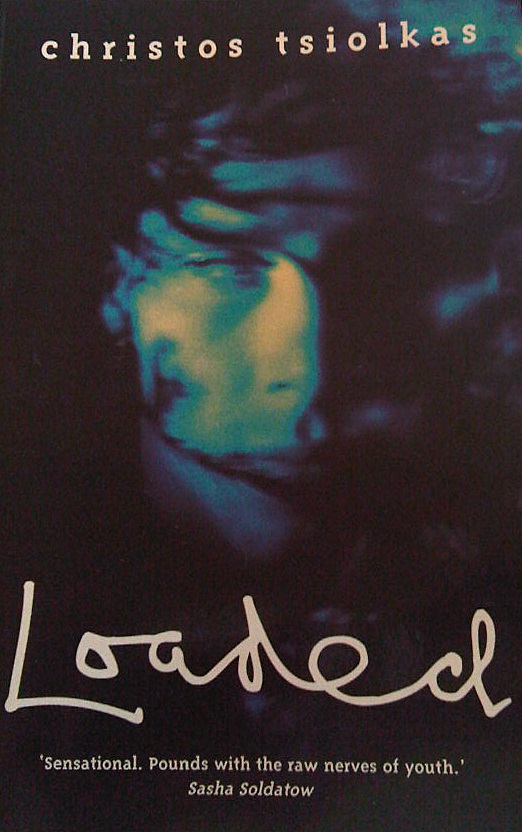

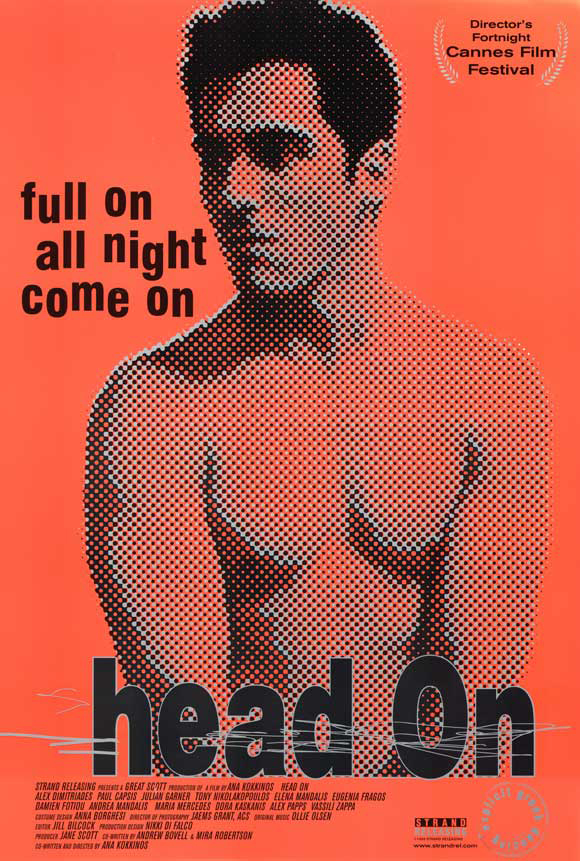

“To be free, for me as a Greek, is to be a whore,” declares Ari, the chief protagonist and anti-hero of Australian author Christos Tsiolkas’ first novel “Loaded” (1995).

Although the nineteen-year old Ari can easily be read as a confused young man coming to terms with his sexual and ethnic identity in the city of Melbourne in the 1990s, his attitudes and behaviours have links with earlier marginal identities in Greek culture. By re-reading Tsiolkas’s central character as not simply “gay” or “homosexual” but as a historical sexual dissident known as the «πουστόμαγκας» (poustomangas) we establish a lineage of radical queer expression for Ari and reclaim a subculture which continues to be ignored and erased by researchers and historians in Greece.

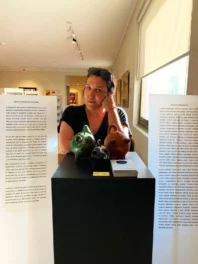

Sitting in front of Mitsias is the young Christos Migos, who later became a popular composer and bouzouki player.

Image colourised and courtesy of the Gennadius Library, Elias Petropoulos papers.

Re-assessing Ari in this way also complicates straightforward interpretations of his character as “gay” and resists the binary notions of sexual identities as expressed in Western discourses.

For Ari to be truly free, he must live in opposition to both the binary renderings of his sexuality and the normative traditions of family and honour, thereby taking his place amongst the social outcasts and deviants that came before him.

There are many kinds of slurs and insults used in Greek to denote these social or sexual “others.” The two used in Tsiolkas’s novel, πούστης (queer), and πουτάνα (whore) are emphatically reclaimed by Ari.

“Those insults have formed me” he says, “they have nourished me,” his pleasures and desires “made sweeter by the contempt they bestow on me in the eyes of the respectable world…”

Although these “loaded” words are pejoratives, they also function as archetypes in the Greek popular imagination and shouldn’t be dealt with exclusively as evidence of fixed attributes or behaviours.

One such “archetype” that is relevant to Tsiolkas’s novel, but which is never explicitly mentioned, is the ρεμπέτης (rebetis); a macho, free-spirited and hedonistic figure who embodies the kind of culture which produced the musical genre of ρεμπέτικο (rebetiko). Among the many proposed etymologies of rebetis is the ancient Greek verb ῥέμβομαι meaning to “wander” or “roam about”, whose connotations fit neatly with Tsiolkas’s character as he traverses the alienating cityscapes of Melbourne.

An analogous term which is less specific than the term rebetis, and which is still commonly used today is the word μάγκας (mangas). As a historical social group, these working-class men — according to Angeliki Vellou-Keil — created “a style of life [in the cities] that represents an opposition and resistance to the bourgeois way of life” and lived in pursuit of “beautiful” things: good company, music, dance, hashish and women.

Although they were rebellious, these manges were generally not interested in politics, and were often dismissed by commentators as a lumpenproletariat. Likewise, when Ari finds himself ensnared in a discussion around Marxism inside a Greek music club, he sings along to a “thirties hashish song”, remarking: “fuck politics, let’s dance.”

But there existed another kind of mangas in the urban milieu of Greece towards the mid 20th century, one that is shrouded in taboos and rarely elaborated upon by researchers. Based on the little we know about this historical figure, the legendary poustomangas (or “queer” mangas) was in the words of folklorist Elias Petropoulos “a passive homosexual, although at the same time highly aggressive and belligerent…[he] didn’t behave effeminately, he hung around the real tough guys [manges], and wherever necessary started knife fights.”

The two words used in this term—poustis (queer, effeminate, passive) and mangas (manly, aggressive, dominant) — are completely antithetical, yet find their synthesis in a word which is a powerful affirmation of these seemingly irreconcilable opposites.

The sexual politics implicated in these terms shed light on conceptions of gender and sexual expression at the time, and also those expressed by Ari in the novel.

In Ari’s sexual encounters, he constantly has to wrestle with preconceived cultural ideas around his behaviours and desires, and those of others. According to Ari, “fucking with Greek men is half sex, half a fight to see who is going to end up on top.”

Before terms like «γκεί» (gay) and «κουήρ» (queer) became more commonplace in Greece, male homosexual behaviour was usually conceptualised in three categories: “poustis” (bottom), “bines” (versatile) or “kolobaras” (top). This meant that men who presented as masculine and took on the “penetrative” role with an effeminate poustis retained their manhood and honour.

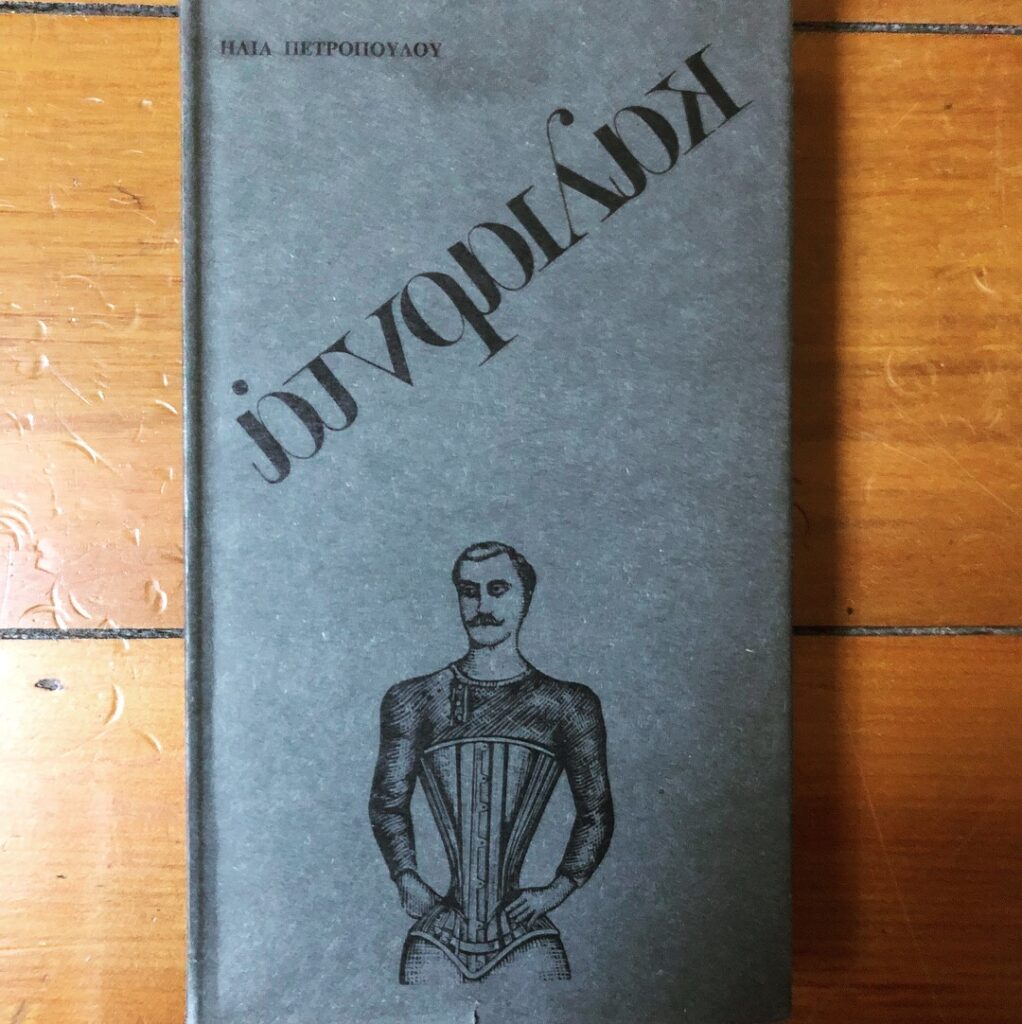

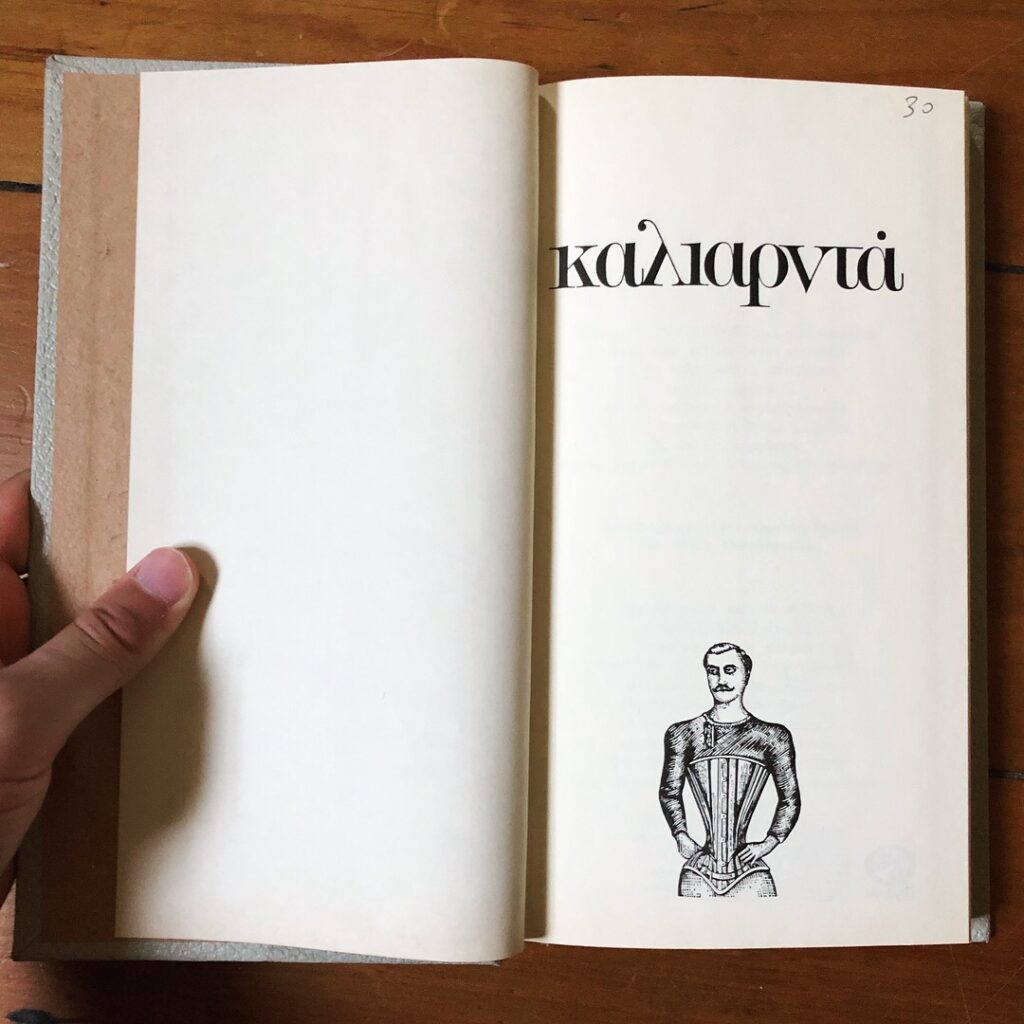

(A 1st Edition copy of Elias Petropoulos’s Dictionary of Greek Gay Slang – “Kaliarda” – published in 1971.)

Unlike Ari’s friend Johnny/Toula, who cross-dresses and is branded as a poustis, the identity of Tsiolkas’s central character is not so clear cut. When asked if he is “gay, straight or bi” Ari avoids the issue, finally agreeing that he is simply “a slut”.

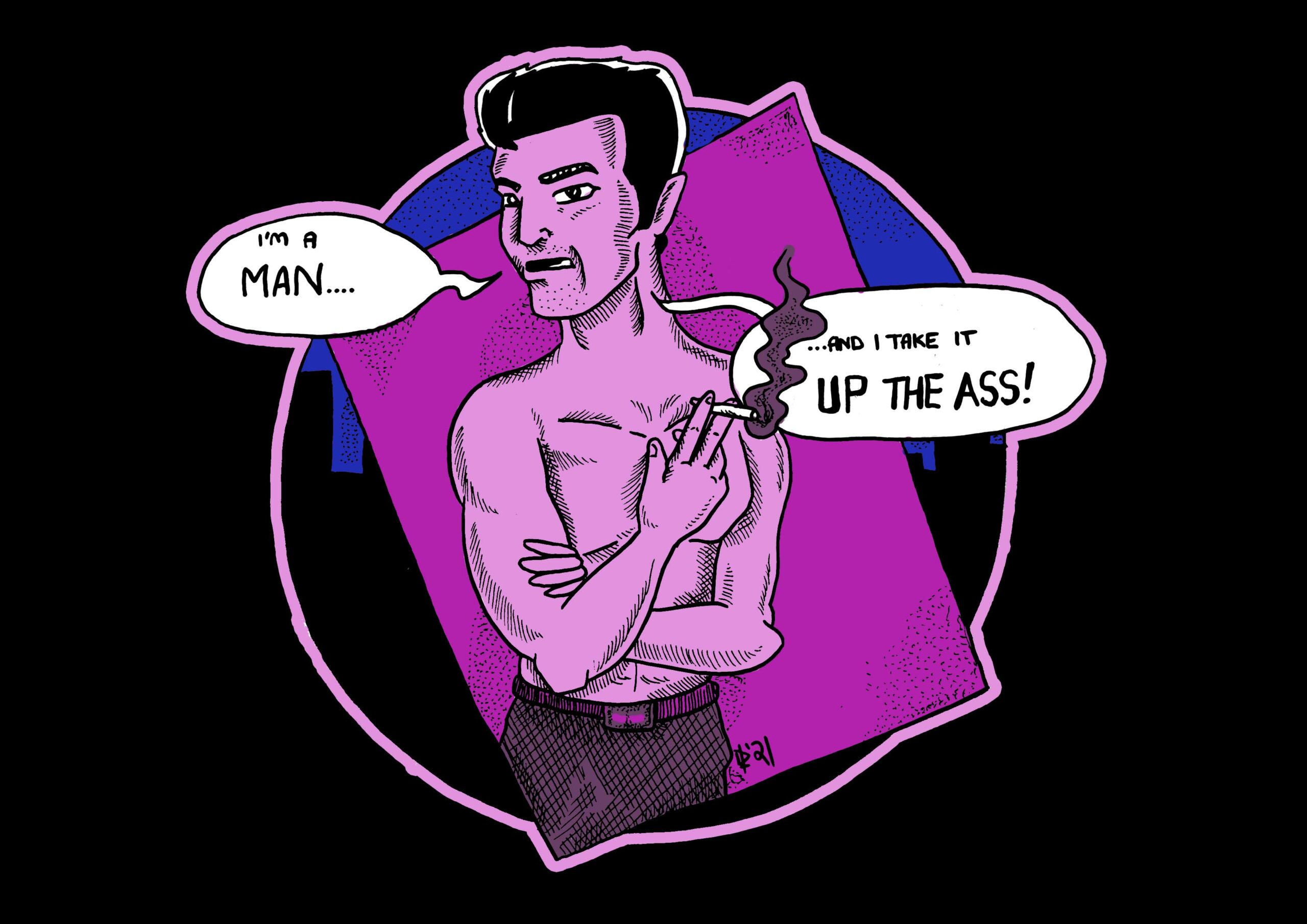

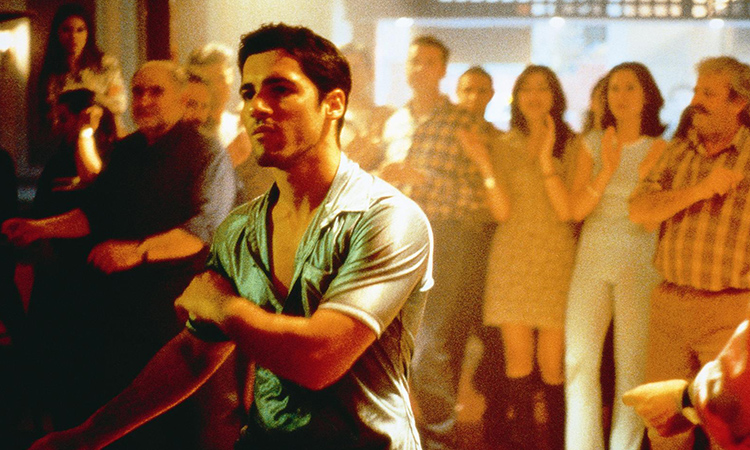

As a kind of poustomangas, Ari plays the part of the “macho”, takes hard drugs, dances the zeïbekiko, enjoys rebetiko music and fucks with men. When told by a friend that he doesn’t “act like a faggot”, Ari flexes his muscles and says, “I’m a man…and I take it up the ass.”

In late-2019 I met journalist Vassilis Pisimisis in Athens, who has written books about the historical sex work and underworld quarters of Piraeus. I specifically asked him why he hadn’t mentioned the poustomangas in any of his books. He replied by stating categorically that many rebetes and manges were “tops”, meaning they had sex with men in the penetrative role, which was less stigmatised and at times even encouraged in their circles, being seen as a hallmark of “manliness”.

As for the poustomangas, he claimed that it was only until after the Second World War that this self-identified appellation was adopted by local roughs, a way of saying “yes I like to take it [from behind], but I am a man, a mangas.”

In conversation with another unnamed writer in Athens, he mentioned that over a decade ago he wrote a blog post on a rebetiko research forum about the poustomanges. However, this inquiry was met with unease and disapproval, and the post was eventually deleted.

The reason why this issue is such a sensitive topic in Greece is that the very existence of such a historical figure undermines the perceived masculinity and heterosexuality of the manges in contemporary discourses.

But in Tsiolkas’s novel, Ari has no recourse to identify as a poustomangas because this queer subculture had largely ceased to exist in Greece by the mid-1970s.

Trans activist and filmmaker Paola Revenioti mentions in her documentary on the gay slang Kaliarda that she knew an older poustomangas called “Petronia the girl from Piraeus.” She elaborates that this kind of queer was no longer common at that time, and now no longer exists.

Even Petropoulos, who compiled his lexicon of Kaliarda in the late 1960s, wrote later on that he knew only two names of people reputed to be poustomanges: Mitsias from Thessaloniki (of whom a photograph exists) and Manolis Manourakis, nicknamed “Manolia” who was eventually killed by The Greek People’s Liberation Army during World War II, although Petropoulos also claims that in pre-war Metaxourgeio “there lived a few well-known poustomanges.”

Far from being irrelevant, these historical sexual subcultures haunt Ari throughout the novel. Although not explicitly evoked or acknowledged, their resonances are powerful enough that their attitudes and behaviours emerge in the form of a character who exists in a time and place far removed from their original contexts.

To break free from the insular and conservative Greek diaspora of Melbourne, Ari must embody the spirit and defiance of these earlier sexual dissidents.

Both haunted by the past and being liberated by his status as an outsider, Ari takes on no fixed identity for himself, not even that of a poustomangas. In no uncertain terms, he declares: “I’m a sailor and a whore, and I will be until the end of the world.”

Article header art by Dan Thrax.