Brian M. Clark has done a lot.

And we mean a lot.

If most are plain bread and butter, he’s a veritable supreme pizza – A man comprising various, seemingly contradictory palettes and flavours, which together, make up a deliciously unique whole.

Born in America during the late 1970s, Brian has spent his life immersed in the creative underground. As a solo creative, a collaborator, and a leader. Creating, curating, forming numerous clubs, societies, and movements – whilst also releasing music, writing, and art.

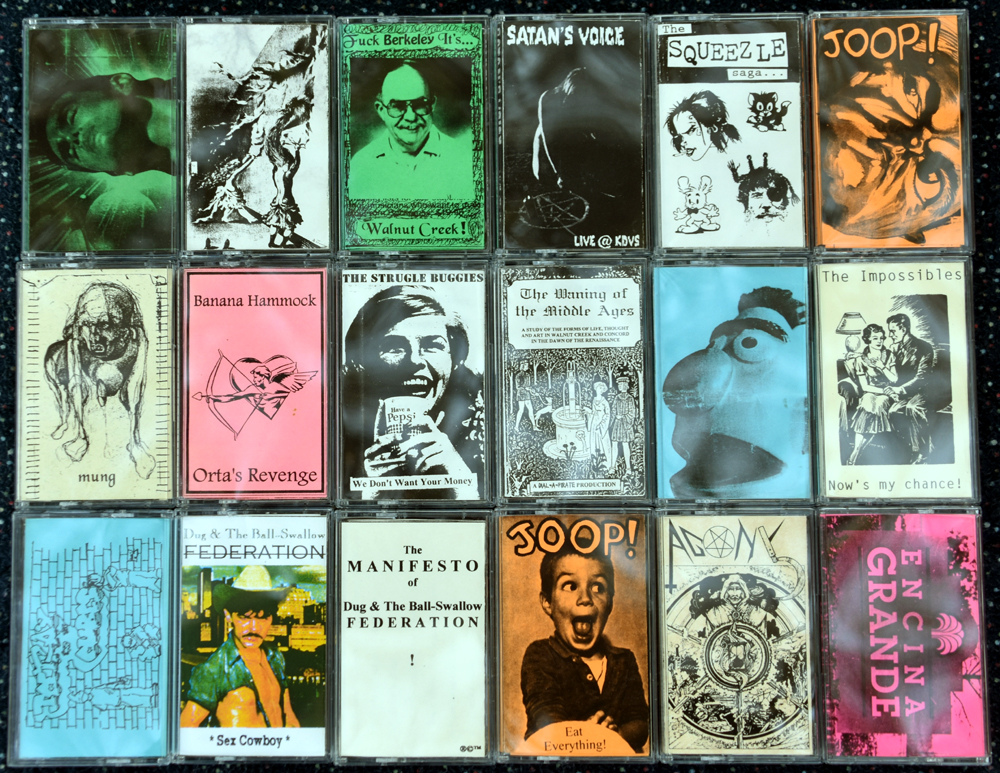

During his late teens and early 20s, whilst studying at high school and college, Brian was a pivotal player in the ‘Dial-A-Pirate Records’ scene. A DIY style label who released a wide variety of cassettes from a number of bands comprising the scenes’ core members; including notable people such as label founder Rob Enbom (of Eat Skull and others.)

After college Brian spent time travelling throughout Central America, Spain, and Europe. Where he developed his initial interest in writing, after selling some of his travelogues to various publications.

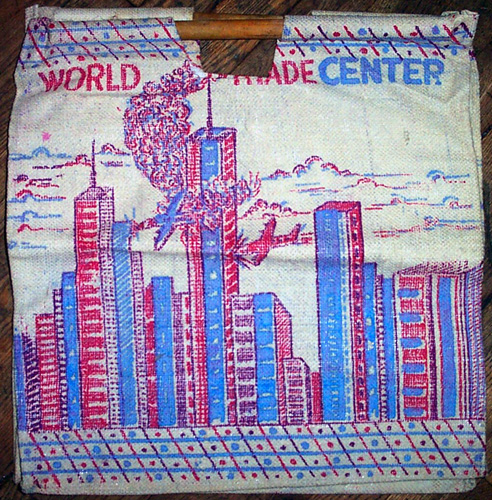

Going on to co-found the ‘Unpop’ art movement with Shaun Partridge and Boyd Rice upon his return to America in 2004. A movement which gained much attention in the early days of the internet, and is fondly remembered today; due to their mish-mash of pop-art-styles, with often controversial themes and subject matter.

In his late 20s, Brian founded his ‘Discriminate Media’ empire, through which he continues to release books and music by himself and others. Such as Ralph Gean, Little Fyodor, and Chthonic Force. Cementing his status as a scene builder.

Art by Glenno Smith.

During his 30s, Brian went back to college where he obtained his postgraduate degree, whilst also continuing to run ‘Discriminate Media’, write and create.

Today Brian is in his early 40s and has recently returned to the world of music himself, via his Unborn Ghost project. A dark and sonically varied solo album featuring music Brian has been working on his entire adult life.

Wanting to get to know him better, we sent Brian some questions to answer over email.

Take a break, mix yourself a drink and sink your teeth into the life of Brian M Clark below…

Bon appetite!

Getting Acquainted

Name and date of birth?

Brian M. Clark.

I was born in Nowheresville, upstate New York, USA, in the late 1970s.

City, State, and Country you’re from?

I grew up in Nowheresville Suburbia, East of the East Bay Area, California, USA.

City, State, and Country you currently call home?

I live in scenic Denver, Colorado, USA.

Photo by Shanti Williams.

Please describe some memories – such as art, music, writing, friendships, adventures, study, romance, politics, travel, work, crime … anything really – from the stages of your life noted below:

* Your childhood:

I had a pretty decent childhood, overall. I grew up in a mid-mod Eichler home in the suburbs of northern California, in a nuclear family with two parents and a sibling, a dog, a cat, and so on. I went to public school and had a bunch of friends who I rode bikes and watched WWF wrestling with.

I played all the kids’ team and solo sports except for (American) football, and had a decent enough number of toys, even though I was jealous of my friends who had Nintendo years before we got one. Nothing much to complain about, in the grand scheme of things.

I was a pretty gregarious and upbeat kid overall.

The only remarkable thing about my childhood is that when I was nine I was in a fairly serious accident – broken pelvis, broken leg, broken arm, and broken jaw in three places. I lost my four upper front permanent teeth and some of the bone under my nose.

I then spent what felt like a decent chunk of my late childhood bedridden with my jaw wired shut, “eating” a liquid diet, pissing through a catheter tube, and shitting in a bedpan. This was followed by some time in a wheelchair, then crutches, and decades of wearing dentures.

I have no memory some of it, but the accident killed off my nascent career as a professional soccer – sorry mate, “football” – player.

Photo by E.K.C

* Your adolescence:

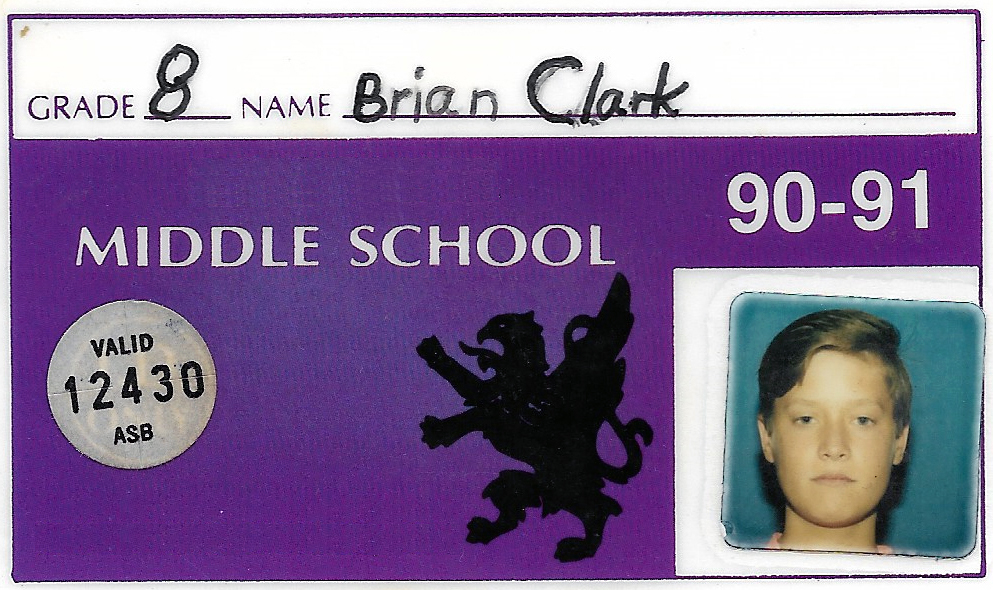

I hated middle school. I grew up pretty much middle-class in a middle-class suburb, but my parents managed to finagle some sort of contrived arrangement where I was able to be bussed-in to a “better” middle school in a neighbouring suburb that was more upper middle class than where I lived.

I wasn’t poor by any definition of that term, but compared to the kids I went to middle school with, I sort of was – or at least they acted like I was. It was really the first time that I became class conscious, I guess.

This was in the late ‘80s and 1990, around the time when athletic shoes became a status symbol. Nike Air Jordans were it, and the boys I went to middle school with all seemed to have Nike Air Jordans, or at least Nike Airs. My mom bought my shoes at a wholesaler we have here in America called Costco. So, I wasn’t “cool” at my middle school on account of that, among other things.

I recall beginning to really dislike people and becoming misanthropic around then; between seventh and eighth grade or so. Things like Beverly Hills 90210, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Vanilla Ice and Bel Biv Devoe were popular at the time, and none of it spoke to me.

My best friend Adam and I sort of informally parted ways at the beginning of eighth grade and began running with different crowds. He got into hip hop, hanging with the jocks, and so on – whereas I started getting into heavy metal music, Dungeons & Dragons, and hanging out with the “bad” kids who did drugs and vandalized things (several of whom didn’t make it to thirty). I never looked the part though, since I was too square and straight-laced, so I was seen as something of a poseur.

Photo by E.K.C

* Your teenage years:

Freshman year of high school for me was 1991-1992 – when Nirvana and grunge blew up, and some of the metalheads who I hung around switched overnight from wearing Metallica and Megadeth t-shirts to Pearl Jam shirts and flannels, and pretended like they’d always been that way.

These were the same people who just six months prior had dubbed me a poseur for listening to metal but not having long hair and dressing like a dirtbag. So I pretty much sidestepped most of grunge when it blew up in the early ‘90s, partly because I just disliked how grunge suddenly transfixed everyone and swept through my high school like a hula-hoop fad – I was skeptical of that, as a freshman.

Sophomore year I discovered punk rock and sort of got into that for a while, and I started singing in a DIY band in the ‘burbs. My friend Dave had just started taking guitar lessons, and after his first or second lesson we decided to start a “band.”

He wrote these really rudimentary two or three chord “riffs” and I wrote and sang the lyrics, and we got his neighbour Heather to play buckets for drums. I believe the first song I wrote was titled “Sexually Disturbed Kitchen Appliances Who Worship The Devil.” We recorded on a boombox and released an “album” on cassette as Living Toupee, which I gave away copies of at school.

I then befriended Rob Enbom, who went to my high school and was a couple of years older than I was, and who claimed to like Living Toupee. Rob introduced me to a lot of weirdo music and took me to shows.

The Bay Area had a pretty good music scene in the mid-1990s, and I was able to go to all-ages shows at 924 Gilman Street in Berkely, as well as a few other places in Berkeley/Oakland and San Francisco. I got really into independent or “underground” music halfway through high school, and would order batches of records in the mail from Lookout!, Estrus, Boner, Dischord, Touch and Go, Man’s Ruin, and other labels. This was all before online commerce was a thing on the then-burgeoning internet. You’d send off for a record catalogue in the mail, and then you’d write a letter to the label listing the records and CDs that you wanted to order, and include a check for the total. It seems archaic now, but that was normal.

It was always exciting to get a package in the mail of stuff I’d ordered three weeks prior, and spend the next month or so listening to a batch of new music. I also spent a lot of time trawling through record crates at Amoeba and Rasputin Records, looking for stuff that was out of print, or imported from the U.K., or whatever. That’s also a thing of the past, pretty much, since the advent of eBay and its imitators; and, more recently, the fact that everything is pretty much free to stream online now.

Photo by Matt Buster.

Rob had started a cassette tape “record label” called Dial-A-Pirate Records through which he released recordings from his band Man-O-Warez and a couple of other local teenage suburban bands. I don’t remember how it came about, but at some point, I ended up co-running Dial-A-Pirate with Rob and releasing a bunch of my bands’ stuff on it.

Meanwhile, I taught myself how to play the acoustic guitar that my family had had in our garage for years, and I started recording my own music. We started churning out albums on Dial-A-Pirate. I was in an instrumental surf rock band called the Impossibles, and a rap group called Ice Tray & Da’ Cubes, and an instrumental horror movie soundtrack band called Agony, and a few others.

It was all goofy and juvenile.

Basically, me and various of my teenage friends would just make up a concept for a band, write some songs, and then get together over a few weekends to record a cassette tape “album” on a Tascam Portastudio 4-track. Then I would design the album cover at Kinkos and make a bunch of copies that we’d sell at school for $3.00 or whatever the next week.

Several people from that teenage suburban Dial-A-Pirate scene went on to do “real” music into adulthood. Rob Enbom is or was in Eat Skull, Sleeping Beauties, and various other bands in Portland, Oregon; Marie Davenport joined The Bananas and The Bright Ideas; and Avi Roig did Harshr and some other bands in Washington. Dave Thompson also played in some Bay Area punk, ska, and hardcore bands. But everything on Dial-A-Pirate was pretty much a novelty act.

Most of it, in retrospect, isn’t that great – in fact, much of it is downright terrible – but it was fun, and it had a weird sort of unselfconscious authenticity and integrity to it.

Apart from Dial-A-Pirate my teenage years were pretty unremarkable.

By and large I wasn’t really a troubled teen. I got decent grades and wasn’t a druggie.

I have the impression that most people tend to rebel against their parents when they’re a teenager, but I feel like I rebelled against my peers more than my parents. Various of my friends started dying their hair, getting piercings, and tattoos – I eschewed all of that. I was an obstinately proud square.

None of that stuff matters now, but I recall it having import at the time, since teenagers are so neurotically status conscious.

A label Brian ran with original founder Rob Enbom.

* Your 20s:

The first part of my 20s sucked. I went to college in Eugene, Oregon, simply by dint of the fact that during their meet-and-greet for prospective students I noted that Eugene had a cool record store called Green Noise and various other “cool” indie shops on one block of 13th Avenue. I therefore hastily concluded on that basis alone that there was a decent music scene there. I was wrong. Eugene had just one all-ages venue called Icky’s Tea House that was way out in the sticks and mostly booked bands that I didn’t give a shit about.

Eugene is sort of a granola hippie deadhead type of college town, and I met very few people there that I had anything in common with or liked at all, so I became sort of a sulking college loner during the three years that I was enrolled there.

I majored in Art in college. I had become interested in art history in my late teens when I discovered Surrealism, so I majored in Art because I didn’t really know what other direction to go in when I got to college. My interest was really more in art history than studio art, however.

I took a course on the history of Dada for which I wrote a final paper on how the inheritors of Dadaism were in the field of music and performance rather than visual art – it was mostly about Einstürzende Neubauten, Nurse With Wound, and Throbbing Gristle having picked up the proverbial Dadaist torch in the 1970s and carried it into the ‘80s. My art history professor was confused but approving.

I took a bunch of studio art classes, as well. Given my interest in Dadaism, Situationism, and absurdity in general, I unfortunately put more effort into trying to create things that were spontaneous, weird, and oftentimes offensive, than I did into actually perfecting any particular skill or craft as an “artist.”

The overwhelming majority of the “artworks” that I produced at the time now seem either mediocre and dull, or else juvenile and silly – but there are a few that aren’t completely terrible. After photographing them I gave them all away to erstwhile friends and acquaintances, most of whom I don’t even know anymore.

I also started another ridiculous band in college with a guy I befriended named Doug Jenkins; he was into indie rock music but was also a classical music buff and knew some music theory. We sort of tried to combine rock music with electronic polyrhythms and Arnold Schoenberg’s notions about serialist music composition.

The result didn’t really go over well.

The songs were these overly technical rock riffs with weird electronic drums, and shouted absurdist lyrics. Doug wrote a “manifesto” explaining to the world how we were the future of music. There were costumes involved. The whole thing was completely fucking ludicrous. I think our biggest hit was “Peanut Butter on My Balls.” We released a couple of cassette tape “albums” on Dial-A-Pirate, and did one short West Coast tour. I think we maybe played four or five shows, tops. Doug later went on to do “real” music with an indie rock band called Bright Red Paper, and then started The Portland Cello Project, which I think he still runs or oversees or whatever.

Photo by Joe Bunik.

Things went south for me in college around 1998. I had gotten into a co-dependent college relationship at age 19 that soured in a fairly epic way around the time that I turned 21, which left me rudderless for a few years. Partly as a result of that and some other ill-advised youthful missteps, I dropped out of college in Eugene and moved back in with my parents in NorCal for a bit, which was predictably awful. I then reenrolled at a college in the Bay Area just to finish up and get a B.A. degree.

While I was a college student in the Bay Area I started yet another goofy conceptual joke band called Satan’s Voice, with my then roommate Avi. Satan’s Voice was an all-MIDI heavy metal band that fondly lampooned the cartoonish excesses of black metal, power metal, and various other metal sub-genres. It was just the two of us, but we made up a bunch of fake band member names like Cross-Turner-Upside-Downer, Lord Christraper, and Stormbringer Von Havoc.

Satan’s Voice played one “live” show on the UC Davis college radio station, during which we talked in ridiculous guttural heavy metal voices between songs and claimed to be a six-member band from Norway. The recording of that was of course later released as yet another a cassette “album” on Dial-A-Pirate. It was absurd, but also kind of great.

Around that same time, while I was in college in the Bay Area, I made a short experimental film that turned out alright and was selected for screening at The Pacific Film Archive in 2000, and then later was shown at The 2005 International Experimental Cinema Exposition in Colorado – but that was kind of the only noteworthy thing I did at the end of college in the Bay Area.

Released in 1999 by Dial-A-Pirate Records; & designed by Brian.

I was pretty miserable in the Bay Area at the time, and I started to romanticize the idea of the globetrotting loner. I started reading a lot of travelogue stuff by George Orwell, Richard Huelsenbeck, and P.J. O’Rourke, and some of Ernest Hemmingway’s expatriate fiction, and decided that I needed to do likewise – “see the world” and get the fuck out of America.

After procuring a passport and visa(s), I spent a few months living in Costa Rica and working as a hotel concierge at a beachside surf-bum hotel; and a few months in Ireland working as a bartender; and then a couple of years living in Spain and teaching English. In Spain I learned Spanish pretty well, made some Spanish friends, and briefly played in a shitty rock band. I embraced Madrid’s “la marcha” – staying out late most nights and drinking to excess often. It was great – just what the doctor ordered. While I was over there, I was able to take trips to Portugal, France, and England, which was also cool.

I was living in Spain when 9/11 happened, which was weird; but maybe not as weird as being in America at the time. My only regret about living in Europe is that I eventually started dressing like a European – wearing turtlenecks, for example – and that’s unforgivable.

Photo by E.K.C.

When I began living abroad in my early 20s I started a blog that my friends back in The States could read, and so I would write about the things I was doing in foreign countries. I tended to get positive feedback on it, so I kept doing it.

The first piece of writing I ever sold was a short blog post that made its way into International Living Magazine. Eventually I decided it was maybe worth my time to try to write more substantive stuff, and eventually went in that direction.

In the second half of my 20s I came back to the USA and lived in San Francisco for about a year; where I worked a dreary office job as an administrative assistant and soon fell into the same antisocial funk that I had been in before moving abroad a few years prior. So, I again decided that I needed to get out of California, and moved to Denver, Colorado, at the end of 2003.

By happenstance I moved into a showspace in Denver called Monkey Mania, which was great – we basically had a party every weekend at which bands played, so I quickly met most of the interesting weirdos in Denver in the early aughts. Then I got a gig managing a small apartment complex – so, free rent and bills, and lots of free time to work on projects.

I lived in Denver from 2003 to 2008, during which time I did a book on Boyd Rice, co-founded an art movement called Unpop Art, co-founded a gentlemen’s pipe smoking club, and started a “real” record label that actually put out CDs and records, called Discriminate Audio.

* Your 30s:

I moved from Denver to Los Angeles in late 2008, right as The Great Recession was coming down the pike. So, that was not ideal because it made finding a job as a newcomer to Los Angeles pretty difficult. I ended up working as a technical writer at a factory in Compton because that was the only gig I could get.

Living in Los Angeles was tough; my commute was gruelling, my apartment was small, and I had trouble meeting people. I got into the Scientific Skepticism movement around that time and started going to Drinking Skeptically meetup events, hoping to connect with likeminded Angelinos.

Generally speaking, the attendees were smart and had solid ideas about the nature of reality but possessed execrable social skills. Some of them seemed like they were straight out of a Central Casting Call for a “Stereotypical Socially Awkward Nerd” character. Nice enough people, but mostly not great advocates for that worldview offline in the real world. That said, I did make the acquaintance of a handful of people from that “scene” who are great, and who I’m still friends with to this day.

I spent a few years struggling to stay afloat in Los Angeles before I finally ended up going back to school at age 34 and getting a postgraduate degree. While I was in school I worked part-time as a bartender and rideshare driver, the latter of which was a real drag. I did find the time to release some music and writing while living in Los Angeles, but by 2012 I was pretty bogged down with school and work, and didn’t have much time for hobbies.

I eventually moved back to Denver in 2017, not long after I turned 40.

Photo by Amber Maykut.

* Your 40s so far:

I have a nice life nowadays, at least at the moment. Since early 2018 I’ve had a job that I’m quite good at and I’m remunerated accordingly, which is something that I’d previously never managed to pull-off. I live in a nice place with my girlfriend of five years. During the coronavirus pandemic we bought each other a kegerator, and we have a decent sized backyard which is great for hosting parties, which we do every couple months or so during the warm season.

Entering middle-age is a bit odd though. Generally, I care a lot more nowadays about being able to enjoy good food, good beer, and good cigars by myself; and a lot less about social events that I’m missing out on. I’m becoming curmudgeonly in my early middle age, but I’m kind of owning it.

Predictably, I find a lot of current pop cultural trends inscrutable and uninteresting, and don’t even know who a lot of ostensibly “famous” people are nowadays. People call me “sir,” and young people regard me with suspicion.

When I go out to shows now, I get the impression that I’m presumed by the other attendees to either be someone’s father or an undercover cop – which I’m fine with.

Creativity Questions: Music

You run the Discriminate Audio record label as part of your Discriminate Media empire…

What’s the idea behind the label?

… and what is it like running a label these days, in the era of streaming music?

I started Discriminate Audio in 2004. I was interested in releasing stuff mostly by solo artists or duos, rather than music by rock bands. Discriminate Audio has released several retrospective “best of” compilations by fairly obscure artists, that I either produced or co-produced.

The idea behind the compilations is that there are certain non-mainstream artists who’ve put out a large volume of material over however many years, which has gone unnoticed because it’s hard to access (self-released, not distributed, and/or not online) or too niche for whatever reason. So, I’ve gone through years (or decades) of that artist’s music, and picked out the hits, and then had the recordings remastered and issued as a “best of” retrospective. I like doing that. I’ve always been fond of Rhino Records, and how they’ve released all these curated retrospective collections like the Nuggets series, and various “best of” or “greatest hits” collections. That said, I’ve also released stuff that’s not compilations, but even that has mostly been studio project stuff by duos or trios, or my solo stuff.

None of it is music by traditional rock bands.

Running an indie record label in 2023 is pretty thankless. All the online articles that come out from time to time about Spotify paying $0.004 cents per stream or whatever, are usually pretty accurate.

The musicians I know who earn a living doing music make their money from touring and selling merch, mostly, since most people don’t purchase music on physical media anymore. But if you’re a “label” then you kind of have to put stuff out on physical media if you want it to be taken seriously by reviewers, radio disc-jockeys, and any other gatekeepers arbitrating whether to give your releases the time of day or not. So that results in upfront manufacturing costs that are difficult to recoup – that’s especially true for Discriminate Audio since the stuff I put out is pretty niche and the artists generally aren’t “bands” that tour and sell merch. I count on people who like it to purchase the actual physical releases, but unfortunately most of them just stream the music – actual physical media purchases unfortunately come in drips and drabs. So, it’s a real uphill battle and it can be dispiriting at times.

The flipside of this, however, is that since it’s my label and it’s not my “real” job, I get to release whatever the fuck I want on whatever timeline I want, and I don’t have to take into account any “notes” from interested third parties. I can take as long as I like to do a release, and do it exactly how I like. Working musicians don’t have that luxury. They have to churn out new material on a timetable, and have it ready to go in time for the next tour, and make sure it isn’t too alienating to the fanbase according to the manager, or the producer, or the A&R guy, or whomever else has a stake in the recording. I don’t have to deal with any of that bullshit, which is nice.

Specifically, left to right: “The Very Best of Little Fyodor’s Greatest Hits!” [2005], “The Amazing Ralph Gean: His Music, His Story,” [2007], & “Delirium Tremens: The Best of Chthonic Force” [2007].

How is your friend, musician, and Discriminate Audio signee Ralph Gean going these days?

… and any news about him and his music to share?

Ralph keeps on Ralphing. He lives in a suburb of Denver and comes into town to play a solo acoustic show about once a year or so. In 2018 I had him over to my place to record a couple of songs, which were released on Discriminate Audio in 2019 as a digital single. I then had him do a spoken word bit for the Unborn Ghost album.

He hasn’t recorded anything in a while, but we’ve recently discussed issuing some of his unreleased recordings, if only digitally online; maybe an album or EP of his unreleased originals, and another one of his covers. He’s supposed to get back to me soon with a list of what he has recorded and wants to release.

Photo by Brian.

You recently released your latest solo album, Airs of Contempt and Derision, under the name ‘Unborn Ghost.’

* Why did you release the album under a group name instead of your own, especially as you have released various recordings under your own name in the past?

I released Airs of Contempt and Derision as Unborn Ghost partly because originally Unborn Ghost was going to be a “band” that I was going to do with Matt Skiba when I lived in Los Angeles, more than a decade ago. He and I batted around a few ideas for names, and that was the name we eventually settled on.

Its genesis was that I was reading a Christopher Hitchens book at the time that had a quotation in the preface from Richard Dawkins, which contained the term “unborn ghosts,” so I said, “How about we call it Unborn Ghost?” And Skiba’s response was, “Yes, that’s it.” I registered the domain name UnbornGhost.com like a decade or more ago, and just sat on it. Skiba then sort of lost interest in the project at some point and moved on to his numerous other musical projects, and then I moved back to Denver in 2017.

I decided to just keep the name Unborn Ghost, even though it ended up being just me recording solo, since I already had the domain name, and it has a nice ring to it.

The other reason for releasing the album as Unborn Ghost rather than under my name is that people can more easily wrap their heads around the idea of rock music from a “band” rather than one guy playing all the instruments on an album. And there’s also the fact that my name is pretty boring and common in the first place.

There are quite a few Brian M. Clarks in America.

Photo by Matt Skiba.

* How did the album come to fruition?

Most of the songs on Airs of Contempt and Derision were written back around 1998 to 1999, when I was sort of a dour malcontent loner. I’d been meaning to record all of it for years, but never got around to it until the pandemic happened and the lockdowns started in 2020. There was nothing to do and nowhere to go for around two years, so I decided to stop procrastinating and just sit down and finally record all of it during the lockdowns. Then it took another year or so to mix, master, and manufacture it on LP, CD, and cassette.

The album was produced, mixed, and mastered by Howard Karp, who’s based in Los Angeles. He contributed a lot to not just the overall sound of the final mastered songs, but also advised on what to include and not include instrumentation-wise, particularly with respect to the drums and drum fills.

I like how it ended up turning out, and I credit a lot of that to Howard.

* Will we be hearing more music from ‘Unborn Ghost’ in the future?

Maybe. Now that the pandemic lockdowns are over, I don’t really have the same degree of free time that I did a couple of years ago. If I do record more music in the near future, I have some other, more upbeat, stuff I want to record first that doesn’t really fit with the Unborn Ghost “vibe.”

Airs of Contempt and Derision is kind of a “dark” album, thematically. That’s because when I recorded it, I tried to stay true to what the original intention of the songs was back when I wrote them in the late 1990s. But I’m not really in that headspace anymore, in my mid-40s, so I probably wouldn’t write songs like that again. However, you never know.

Released by Discriminate Audio; with art by Sara Lucas aka Hello The Mushroom.

Creativity Questions: Writing

You put out an interestingly titled book in 2010 called Fuck All You Motherfuckers…

What’s the deal with that?

Believe it or not, there was a time when Twitter was an entertaining online space, around 2009 to 2013 or so. Comedians and weirdo anonymous accounts would post jokes, some of which were pretty amusing. I did the same, for a time. Most of my tweets were just intended to make a girl that I was dating at the time laugh. Eventually I got bored with it and stopped tweeting. I then decided to pretty much stop using Twitter and compile my jokey tweets into a little book, which was fairly easy to turn around without much work.

People seem to like Fuck All You Motherfuckers and find it funny, but of course humour is very subjective – some people have hated it completely, or it just didn’t “land” with them. Oh well. Regardless, I’m told it makes for a good coffee table book or bathroom reading because you can just open it randomly and read it for a couple of minutes and then put it down again.

Published in 2015 by Discriminate Media.

We know you have contributed to much loved rag, Modern Drunkard Magazine over the years.

How did you come to connect with them?

I first came across Modern Drunkard when I was living in San Francisco in 2002. My girlfriend at the time was the magazine buyer at a hip indie bookstore, and she brought a copy of it home one day and was cracking up about an article detailing an imaginary drinking contest between two famous dead writers – “Clash of The Tightest.”

When I moved to Denver in 2003, I randomly ended up meeting the editor of Modern Drunkard, Frank Kelly Rich, within like a week of arriving in the city. He initially didn’t like me at all, but eventually that turned around and we ended up becoming pretty good drinking buddies.

I attended the first three Modern Drunkard conventions in Las Vegas (2004), Denver (2005), and then Vegas again (2006). I did a few interviews for the magazine, in which I queried musicians, filmmakers, and writers about their drinking habits. Eventually I wrote a polemic screed called “Why I Drink” for the magazine that I guess has gotten some traction online over the years. I also ended up writing and recording the instrumental film title theme for Frank’s to-be-released indie film Nixing The Twist.

Frank is a fun guy. Every time I have a party, I make sure to invite Frank, because it’s not really a proper party unless he’s in attendance.

What’s news with you on the writing front?

Not much. I write constantly as part of my day job, which leaves me burned out on it afterwards. I’ve been toying with the idea of releasing a collection of stuff I wrote when I was in my 20s, but I haven’t had time to get to that, and my recollection of most of my old writing is that it’s probably largely self-serving “cringe” as the kids say nowadays.

I’m not sure it’s worth putting in the effort and the time. But maybe.

Creativity Questions: Art

There has recently been a fair bit of renewed interest in Unpop Art – The since-ended art movement that you were a founder of, and key player in…

* For those at home who may be unaware – What exactly was Unpop?

Unpop was an online “art movement” that I founded with Shaun Partridge and Boyd Rice in 2004. At its height it was a group of eleven American artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers whose work tended to explore the theme of unpopular / unpleasant / upsetting subject matter expressed or executed in a “pop art” or fun and playful style. Its heyday was the early days of social media – late Friendster, and then MySpace, and finally Facebook, back before social media sites were governed by algorithms and the internet was more of an unmediated free-for-all.

Essentially Unpop was sort of a formalized version of what would now be derisively dismissed as “edgelording” or “shitlording,” I guess. An online collection of offensive-and-upsetting-yet-fun-and-whimsical artworks, texts, recordings, films, and “readymade” cultural artifacts all centred around the conceptual premise of Unpop and presented as an “art movement” with members living throughout the United States.

It was only around for half-a-dozen years, but it got some attention for a while.

Photo by Kaleidoscope Partridge.

* What were you and your fellow founders / members trying to achieve with Unpop?

That’s an embarrassing question. I had my own reasons for doing Unpop that I felt were valid, but looking back I now think I was a bit naïve regarding what motivated some of the other members of Unpop. I gave several interviews to magazines and websites in the mid-aughts in which I laid out these overwrought explanations for what Unpop was about and what it meant, and nobody involved with Unpop ever disagreed with my take on it, but in retrospect I think it was lazy of me to think that that meant they agreed with me.

I personally saw Unpop Art as an attempt to forward logic, reason, and rationalism; the idea being that it’s silly and childish to get upset and bent out of shape over an inanimate object like an artwork or a piece of writing or whatever, and that we should all, as adults, be able to process upsetting concepts stoically, because banning ideas or words or whatever – expression alone – does nothing to effectuate change in the real world or do anything to address its real problems.

In other words, declaring certain subjects as “off limits” as the premises for jokes or art doesn’t eradicate the actual real world subject that’s being banned from expression; it just drives the topic underground, thereby giving it the intriguing allure of the taboo. And since unpleasant subjects are based on real things in the real world, we might as well be able to joke about them, and maybe use humor and art to grapple with them, which is better than just suppressing discussion of them – because that doesn’t really do anything about the subject in question. It’s like the proverbial ostrich sticking its head in the sand.

This one designed by Brian himself back in 2004.

I also saw the idea of being “offended” by something as being an active choice that someone affirmatively makes, rather than something passive that happens to them – and further, that what is deemed “offensive” is a subjective judgment and not really rational because morality is subjective, provincial, and changes over time (unlike ethics, which I saw as being objective, fixed, and universal).

I also saw the idea of “being offended” as both entitled and performative. People living in ghettos, favelas, and trailer parks generally don’t have the luxury of worrying about being “offended” by things, and it usually doesn’t matter if they are anyway – it’s typically the affluent and overeducated who are “offended,” and often on behalf of others. I thought that was disingenuous and slimy – the notion that the most privileged people in society get “offended” because they don’t even want to have to think about all the unpleasant and upsetting things in the world, let alone experience them or deal with them. I wanted to annoy and irk those people.

So, the idea to me was that Unpop was a good vector for advancing that worldview because it sort of alchemically fused unpopular ideas with fun pop aesthetics, which made them more palatable, or at least less dismissible.

That was how I thought about Unpop when we started the Unpop Art Movement in 2004.

Two decades later, I still more-or-less have the same attitudes that I did in 2004 regarding the concept of “taking offense” and censorship, but it now seems pollyannaish to me that I presumed everyone else involved in Unpop was doing it for reasons that were similar to mine.

That was just my take on Unpop.

There were eleven people involved, some of whom I never met in person, or in a couple cases never even spoke to on the phone. Some of them had similar views of what Unpop was “about” as I did, but others had completely different motivations and aims for their work. I didn’t realize that at the time.

In retrospect think I was just naïve, convinced of my own correctness, and swept up by the fact that people were paying attention to what I was doing, so I overlooked incongruous things that didn’t fit with what I wanted Unpop to be “about.” I also now think it’s naïve to imagine that you can put something out into the world, and assume that people will give a shit about what your intentions for it are – even if you clearly lay them out. People don’t care what you’re trying to “do” with your art or music or whatever. They see what they want in it, and take what they want from it, regardless of what your aims for it are. I was oblivious to that at the time as well.

Specifically works by – counter clockwise from top left: Boyd Rice, Shaun Partridge, Adam Parfrey, & Gidget Gein.

* Why do you think Unpop is back in the zeitgeist, and what are your thoughts on Unpop’s legacy today?

I’m not sure that Unpop is back in the zeitgeist. I rarely hear about it anymore, which is fine by me. That said, unfortunately, Unpop is more relevant now than it was when we started it back in 2004.

I remember, maybe around 2005, thinking that Unpop had missed its moment, because there were all these things coming out in popular culture that sort of usurped Unpop in a more mainstream way, especially on television: Chapelle’s Show, South Park, Wonder Showsen, The Sarah Silverman Program, The Whitest Kids You Know, Family Guy, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia – they all started doing more and more “edgy” stuff in the mid-aughts, and I thought, “Well, we had our moment of being on the cutting edge of this stuff, but we’ve been overtaken.”

I thought that the wave had crested and broken on uptight buzzkill culture policing, and Unpop would only be of diminishing relevance from the mid-aughts on. It didn’t occur to me that the culture would do a 180-degree turn around 2015 and tepid “political correctness” would evolve into much more censorious “cancel culture.” It’s disappointing. I would have much preferred Unpop to now appear irrelevant, dated, and quaint in the rear-view mirror of culture, because society got over all that humourless tongue-clucking busybody Church Lady stuff and moved on – instead the opposite appears to have happened.

Curated by Brian.

* Why did Unpop as an art movement end?

… and do you have any plans to revive it?

When we retired Unpop in 2010 it wasn’t because of shifting cultural trends or anything like that – it just stopped being fun, due to interpersonal drama between the various members. One of the members was kicked out for being a deadbeat, then another member overdosed on heroin and never woke up again, then another quit, then two members had a feud, and so on.

Since then, a couple more former Unpop members have died.

I still have the domain name UnpopArt.org, but I’m not doing anything with it. Unpop was mostly a headache for me, personally. It was supposed to be fun and funny – and it was, for a while – but it attracted a lot of unstable people into its orbit who made my life difficult, and it’s generally not something I want anything to do with nowadays.

I have moved on to other things, and am not interested in reviving Unpop.

It was mostly a pain in the ass.

Inspirations & Influences

When and why did you first become interested in music, art, writing, esoterica; and everything creative?

… and any pivotal moments or influences regarding each of them?

Music: As a kid in the early and mid-1980s I spent a lot of time in the car because my family routinely took long road trips to see my grandparents as they were starting to descend into Alzheimer’s decrepitude and lose their mental faculties. To keep me occupied in the back seat of the car, my parents bought me a Walkman and a bunch of old radio plays on cassette to listen to, like Abbott & Costello, The Life of Riley, and Dick Tracy.

At some point they got me a couple of cassettes of Cheech & Chong’s albums. I don’t think my parents really understood who Cheech & Chong were, or what they were about, because although they were an audio sketch comedy duo like Abbot & Costello, the material on Cheech & Chong’s albums was pretty unsuitable for a kid in elementary school. But I found it fascinating. There were all these comedic references to drugs and sex and whatnot, and I listened to them intently, like a prepubescent hippy culture anthropologist, trying to figure out what they were talking about. And I really liked the musical numbers, like “Earache My Eye” and “Get Out Of My Room.”

Then I discovered Weird Al Yankovic through a friend, and became obsessed with his stuff. I can probably still recite most of the lyrics to the album Dare to Be Stupid if necessary. That was the music that grabbed me and that I got into as a kid, and into my early adolescence: Weird Al, Cheech & Chong, Monty Python – it was all “novelty” music.

When I later started playing music early in high school, it was through the lens of novelty music rather than the “real” music that was popular among teenagers.

Art: As a kid I dug The Far Side and Calvin & Hobbes. I also liked Patrick Nagel and the sort of Maimi Vice-type of neon aesthetics that were popular in the early ‘80s.

I went through a phase in middle school of being really into comic books; stuff like Boris the Bear, Groo the Wanderer, Milk & Cheese, and the standard superhero stuff.

In high school I had to write a paper for Spanish class about a cultural figure from the Hispanosphere, and I chose Salvador Dalí because I liked his weird paintings. That then, circuitously, led me to learning about Surrealism and getting into 20th Century art history more generally in my late teens.

Writing: In middle school I read forgettable pulp fantasy novels.

In high school I liked all the same dumb books that everyone likes in high school, none of which are worth mentioning.

Esoterica: I’m not into stuff like the occult or “esoterica” in that sense at all; but I do tend to be interested in things that exist on the margins of culture and society. I’m not sure why.

Who are some of the specific musicians, artists, writers, and filmmakers who’ve influenced you after childhood, during your formative years?

… and what was it about their works that so inspired and moved you?

Music: As a teenager I was really into The Melvins, The Mummies, and Big Black. I think that what I liked about those three bands, even though they have little in common sonically, was the attitude and approaches they had. They kind of each stood out and defined their own space in music, and didn’t really fit neatly into pre-existing genres.

I remember being played Lysol and Bullhead by the Melvins when I was maybe 15, and it blew my mind. I had up to then been listening to a lot of ostensibly “heavy” music by heavy metal bands that had albums with spooky-dooky artwork and badass logos, but the music was often overly technical to the point where it got in the way of itself, the lyrics were usually cheesy or stupid, and the vocals were often either too operatic or too guttural.

Lysol and Bullhead were orthogonal to all that; it was like, here was this band with a silly name – Melvins – and their record covers had things like an illustration of a fruit basket or some other innocuous thing, and yet sonically they came out with just this massive wall of drop-tuned distortion backed up by thundering drums. I was like, “What the fuck is this?!” I ended up seeing the Melvins live with my friend Matt a bunch of times in the Bay Area in the mid-90s. My high school yearbook quote was one of their nonsense lyric lines. It’s been interesting to see how a whole scene of stoner doom music has evolved since then – that didn’t really exist back when I first encountered The Melvins.

Big Black had already broken up by the time I discovered them, but they piqued my interest because they had their own unique sound and didn’t really fit anywhere: a fairly minimal drum machine, tinny guitars and trebley bass, lyrics that were about weird dark stuff like mass pigeon kills or working in a meat processing factory, and these stark minimalist album covers that looked like they were precision technical illustrations but were also really bright and compelling.

There was something bleak and cynical about their overall “vibe” that really appealed to me as a teenager.

The Mummies had also already split up by the time I became aware of them, but I liked them because on record they just seemed to capture the spirit of rock n’ roll more completely than any other band that I was aware of. They wore full mummy suits, so you didn’t really know who they were (which I realize, the Residents did a version of first), and they were high energy and fun and obnoxious.

They only put their stuff out only on vinyl, at the height of CDs being “cutting edge” in the 90s, and did obnoxious things like put one half of a song on Side A of a 7″, with the second half on Side B. I just thought they embodied rock n’ roll, basically.

Writing: In my early 20s Griel Marcus’ Lipstick Traces made an impact on me, as did Calvin Tomkin’s biography of Marcel Duchamp, in addition to the travelogue writers mentioned earlier.

I was also pretty heavily influenced by Luke Rhinehart’s The Dice Man, and the Pranks! book from Re/Search Publications – both of which were “bad” influences on me during that tumultuous time in my life. None of that made me want to be a writer though; I sort of fell into that by happenstance, later on.

Film: As a kid I really liked the old Pink Panther series of films with Peter Sellers, and of course stuff directed by Mel Brooks, Carl Reiner, Ivan Reitman, Harold Ramis and their ilk.

In my 20s I did the thing a lot of young people do where I got into decadently dark stuff like Gaspar Noé, Todd Solondz, Takashi Miike, and Michael Haneke – but now that I’m in my mid-40s I tend not to want to be bummed out by a film, so I don’t really go for that kind of thing anymore.

Released by Discriminate Audio.

Who are some of your favourite contemporary musicians, artists, writers, and filmmakers?

…and what is it about their works that so inspire and move you?

Music: Nowadays I like the work of Justin Broadrick, Sune Rose Wagner, Scott Hull, and Matt Pike. I like that they each do multiple projects, even if I don’t necessarily always like everything that each of them has done.

Art: I don’t really pay attention to visual art anymore, but I still like old black-and-white print stuff by Gustave Doré, Max Ernst, Virgil Finlay, and Albrecht Dürer.

I also still like a lot of the original pre-WWI Art Nouveau stuff.

Writing: I think my current tastes in prose are pretty pedestrian for someone my age.

Nowadays I read a lot of pop-sci nonfiction from authors like Michael Shermer, Jim Al-Khalili, Dan Ariely, and others. I also like biographies and historical nonfiction by authors like Erik Larson, Geoffrey Wolff, and Wayne Curtis.

I like Jon Ronson’s books that sort of blend history, journalism, and autobiography. I don’t read much fiction anymore, but I still like Joseph Conrad’s novels and John Updike’s short stories.

I usually recommend that everyone read Carl Sagan’s The Demon Haunted World and Martin Gurri’s The Revolt of The Public. Apart from those two, Florence King’s With Charity Toward None, Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety, and Gaddis and Long’s Panzram are all also worth reading (presuming an interest in the subject matter).

Film: I think my current film tastes are also pretty pedestrian. I like The Coen Brothers, Stanley Kubrick, certain of David Fincher’s films, and generally most stuff that makes it to The Criterion Collection. Stuff that’s just well-made and compelling, but isn’t trying to be preachy.

I also still like American comedies from the ‘80s that you can watch over and over again, like The Jerk, and Vacation.

Originally published by Creation in 2007, & republished in 2015 by Discriminate Media.

The Partridge Family Temple

You are directly and tangentially involved with many members of the religious group The Partridge Family Temple (PFT), such as Shaun Partridge & Boyd Rice, who were also co-founders of Unpop. As well as having released some PFT related music via your Discriminate Audio label.

… and we wanted to know:

What are your thoughts on the whole PFT scene?

I know Shaun and Dan, the two founders of the PFT, and I’ve known various other PFT members over the years. I released a 7″ vinyl single from The Unpop Sound on Discriminate Audio; they’re a three-piece studio project comprised entirely of PFT members.

I like the idea of the PFT. It’s fun.

I think they should consider putting in the work and getting some kind of official legal recognition as a religious organization, with tax-exempt status, and the various other perks that come with being a church in America.

Released by Discriminate Audio; with cover design by Joel Ryan Brandon.

Are you a PFT member yourself?

… if so, please share your Temple name!

No, I’m not a member of the PFT. They sent me a laminated PFT card at one point, that I still have somewhere, but I’ve never adopted the Partridge surname or “joined” the PFT.

I tend to dress pretty nondescriptly, I don’t really dig the ‘60s–‘70s aesthetics or the music, and I’m a nonbeliever – so overall I’m just not a good fit for the PFT. But I appreciate it from the outside.

It’s amusing how it still freaks people out; that there’s a real-life modern religious cult based on the worship of archetypes embodied in characters from a long-ago-cancelled ‘70s television show. It’s pretty brilliant, and you have to respect the longstanding level of commitment to 24-7 Fun on display by the PFT.

They are not fucking around.

Do you have any PFT related tales to share?

Yes, but nothing I’m going to put in writing.

What does God mean to you, anyhow?

I’m an atheist, or an agnostic, depending on how pedantically you define those terms – but I’m a little envious of religious people. It must be really nice to believe in God.

I just can’t get there.

Photo by Zhawna Siegwarth.

Odds & Ends

Personal motto(s)?

It’s not necessarily a personal “motto” per se, but I’m fond of a quote attributed to John Dryden in 1681:

“Beware the fury of a patient man.”

If you had to explain your creative endeavours to some recently crash-landed aliens…

What would you tell them?

If I met recently crash-landed aliens, I think there would probably be much more important things to talk about than my creative endeavours.

If you could live in any place, during any historical era, when and where would that be?

… and why would you choose that time and place?

I like living now, where I live. I have access to pretty much every movie ever made and every song ever recorded; instant video and voice chat; basically infinite information – and all cheap and easy to attain. Even the fabulously wealthy of the past didn’t have most of the conveniences that the average person in the modern West takes for granted, like on-demand electricity and climate-controlled homes.

I’d rather not trade all that for a chance to live in the Victorian era or Ancient Rome or whatever. Imagine living in a time before the invention of anaesthesia? Fuck that.

People who romanticize the past haven’t really thought it through all the way.

The past is mostly awful.

And Denver is the best city in America, as far as I can tell. It has all the amenities of a “big” city (a music scene, an art scene, museums, a symphony, good bars and restaurants, and so on), without most of the things that make “big” cities unlivable. Denver also has a sort of small-town charm to it, although that’s fading.

I can’t see living elsewhere at the moment, at least in the United States.

What role did toys play in your childhood?

… and any favourite toys you remember?

Toys were a pretty big part of my childhood.

Toys in the mid-1980s in the U.S. were great. GoBots came out when I was in like first grade or so, followed by Transformers, both of which were amazing. Later, there were a lot of fun gross-out toys in the mid-‘80s; Mad Balls, Creepy Crawlers, The Mad Scientist, and so on. There was also Micro Machines, Army Ants, M.A.S.K., and various monster toys.

My parents didn’t get me a lot of that stuff, but if I didn’t have it at least one of my friends usually did, so I still got to play with it.

The mid-80s was a good time to be a kid in America. Garbage Pail Kids cards started being released when I was in second or third grade and they were everything, and Wacky Packages from the ‘60s were reissued at some point, too.

G.I. Joe still looked like actual military toys (rather than being in neon colors); toy guns still looked like real guns; Pee-Wee Herman was on television every Saturday morning; and Mad Magazine was still in print.

Best of all, the internet didn’t exist yet.

Of everything you have done so far, what would you most like to be remembered for?

Given a long enough time horizon, I won’t be remembered.

Neither will you. Nor will anyone reading this.

That’s fine by me.

If people wanted to check out your stuff, work with you, or buy some of your wares, where should they visit and how should they get in touch?

Most of my stuff (or links to it) is on BrianMclark.com and/or DiscriminateAudio.com.

Links

- Brian M. Clark – Website

- Brian M. Clark – Facebook

- Brian M. Clark – Instagram

- Brian M. Clark – twitter

- Brian M. Clark – Discogs Entry

- Brian M. Clark – Goodreads Entry

- ‘Discriminate Media’ – Website

- ‘Discriminate Media’ – Online Store

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – Bandcamp

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – Spotify

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – Instagram

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – twitter

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – Facebook

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – YouTube

- ‘Discriminate Audio’ – Discogs Entry

- Unborn Ghost – Website

- Unborn Ghost – Link to Buy Airs of Contempt and Derision via Discriminate Audio

- Unborn Ghost – Link to Listen to Airs of Contempt and Derision via BandCamp

All images supplied by Brian or sourced online.