Born in 1976, Gyula Noesis is a Magyar(Hungarian)-Italian artist and writer, a former Jehovah’s Witness, and a kind of stoic ascetic. He sets rules for his life and forces himself to follow them, no matter how constraining and abstruse they may be; using self-control and will to correspond to a romantic ideal of his own.

Gyula’s artistic activities involve music, painting, video, photography, and scenic arts. His major work, however, remains his as yet completed novel, “Outrecuidances Within the Crotch of a Desperation.” Currently at about three thousand pages to date, it among other things, describes, through the prism of his perceptions, an eclectic culture that he assiduously cultivates, through carefully planned experiences that lead him to sometimes put his own life in danger.

Gyula’s persistent interest in sex and death crosses the whole of his productions, which he qualifies as “secretions” as they are comparable to emanations of his organism. He ruthlessly documents his daily life as a helpless spectator of his own decline.

Based in France and Italy, he travels the world essentially to reach the ultimate pleasure of scribbling his trajectories on a map.

To date, Gyula has worked with various performers such as Jean-Louis Costes, the Italian contemporary theater company Kinkaleri, the collective Bongoût (now Beuys On Sale), and Nico Vascellari; along with musicians such as Xavier Chevalier from the grindcore band Blockheads, Frank “Rat Bastard” Falestra, Nicola Vinciguerra from Fecalove, and Merlin Ettore from Sorcery.

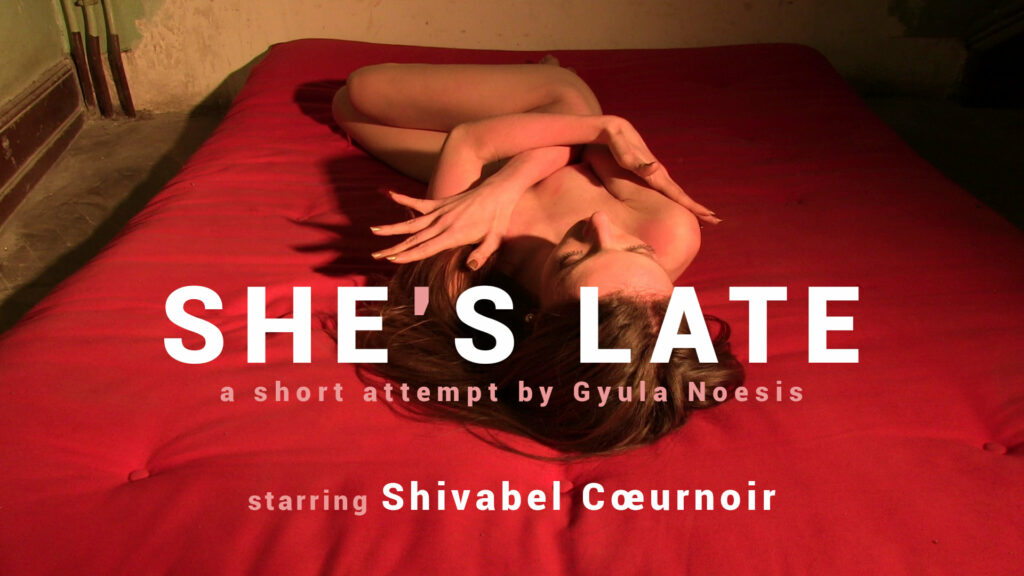

In the recent years, Gyula has travelled to the Amazon for a pain ritual, and to both Ukraine and Moscow for performances and pornographic art projects. He has crossed Armenia on foot and became blind for 48 hours because of snow blindness, and has been extensively working on a series of nude photographs and paintings – His short porn/horror film “She’s Late” with the sadly recently deceased Shivabel Cœurnoir was selected for the Sadique Master Festival 2022.

Gyula is currently in Asia for another series of initiatory experiences, to refine his novel, and with much more to come.

Wanting to get to learn more about Gyula, I met up with him for a long discussion, which was then later solidified over email; check it all out, below…

You are an artist and your work is very diverse – You write, paint, perform… You dance, make music, and make films.

Could you describe these activities and how they relate to each other?

Is there some matter that runs throughout your work? If so, what is it?

All these modalities of expression are connected to my body and to my awareness of its degeneration until the reallocation of its molecules to other forms of life. To the perception of death as an anomaly.

They are connected to mine, to my body, and to the others, to yours, which I wish to touch and abuse in order to test them and experience their materiality.

This interest in people suddenly became hypertrophied when, alone and starved on the Kamchatka Peninsula, immersed in the landscapes I had dreamed of all my life, surrounded by grumbling snow-capped volcanoes whose magnificence could not be described other than by a shrill scream, I realized that the dullest of human beings was infinitely more complex, and therefore worthy of interest, than any of the mineral, vegetable, or animal structures I could approach. From then on, I refocused on these persons that bodies are.

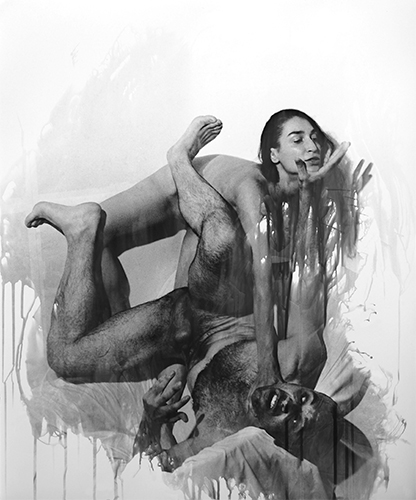

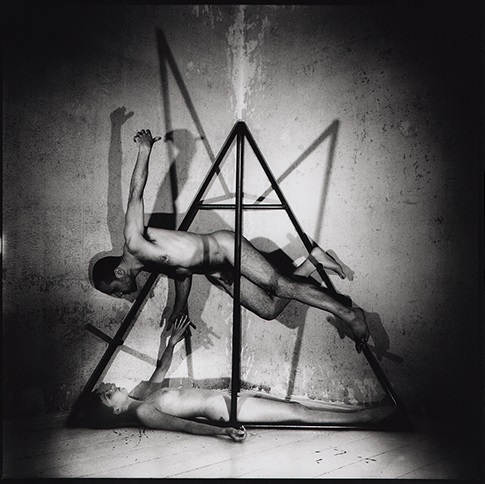

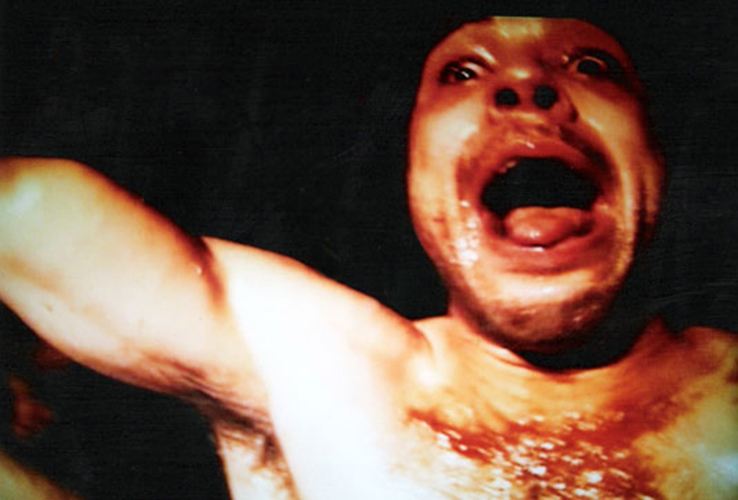

I write about the laborious refining of a human soul (which I believe to be made of neurons and glial cells); I paint by brutalizing with all my body coatings, tools, and surfaces; I film and photograph bodies in distress; and on stage, I try to sweat blood as if suffering from hematidrosis.

Each of these processes is indispensable to me.

Only one is missing from my arsenal of means necessary to express myself fully: architecture. A neglected part of who I am could only be expressed through architectural achievements.

If, moreover, sex, as an activity and as an object, is a preoccupation that emerges from all facets of my work, it is because it connects the two main events of our lives, namely our birth and our death. All our gesticulations have their origin in the preoccupation with death and the lust for sex. The whole history of art is about this, when we reduce the equations to their most stripped-down form.

So, we should approach these themes frankly, head-on, without beating around the bush.

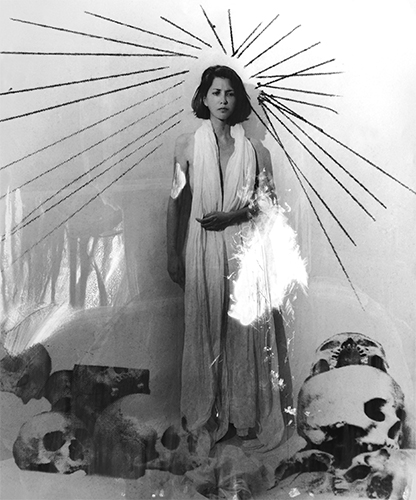

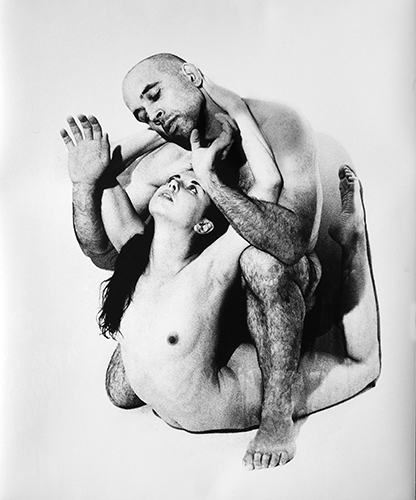

With the images here taken in Kiev, Ukraine, during the Summer of 2017.

For many years now, you have been going on long travel sprees, so far mainly in South America, where you put yourself through ordeals, given yourself painstaking tasks, and you put yourself under very difficult conditions.

For example – Upon trying to cross Kamchatka, you almost starved to death. You’ve climbed up mountains, crossed deserts with no adequate equipment or training. Many people question why someone would do that to himself.

Are you a masochist?

Why do you risk your life and health on these adventures?

I believe that comfort cannot produce anything honourable — a comfort in which I bathe most of the time. I believe in the constructive faculty of suffering. Everything in me that is valuable has been generated, if not by suffering, by a form of discomfort.

I like comfort, I seek comfort, but I could not enjoy it if I knew I could not do without it, if I felt dependent on it as I do on eating and sleeping. I want my dependencies to remain minimal, not create new ones.

In France, the expression “avoir la belle vie” refers to a life of comfort and pleasure. However, I do not see how such a life could be aesthetic. Only a life made of suffering, discomfort, pain, exhaustion and discomfort can be ‘photogenic’.

As an artist, I want to produce beauty; but it is not possible to secrete beauty without having made oneself beautiful through tribulations. All the trials I undergo (being both a student and his master) are exercises in self-control.

I exposed myself to disgust during the tour with Jean-Louis Costes (Le Culte de la Vierge/Holy Virgin Cult, 2002-2003, cf. Sucs caustiques, 3rd movement of my text); to pain on the occasion of my accession to the rite of passage of tucandeira with the Sateré-Mawé Amazonian natives (cf. Mère Nature est étroite, 11th movement of my text); to the fear by going to Petropavlovsk to begin an adventure that I thought had to be fatal to me (cf. Canevas autocratiques un lombric à la commissure des lèvres, 5th movement of my text).

In the train from Berlin to Moscow, toward the airport from which I was going to fly to Siberia, I sobbed in terror in the arms of a nineteen year old stranger to whom I had just confided my panic. My intention was not only to go through Kamchatka on foot, but to continue my journey to the Bering Strait (to cross on unpredictable moving ice, as Dmitry Shparo and his son did), then to Alaska, Canada, the Cascade Range, and, finally, to Ciudad de México after a journey of at least six years. Contrary to my expectations, I came back home with my tail between my legs after only one month, and this after having lost 21 kg (46 lbs) in 27 days and having almost drowned in a freezing water too tumultuous to be swum through, notably weakened and with the help of only one arm (the other one being monopolized by my backpack, which I was holding by a strap ready to unload it.)

No, I’m not a masochist, I don’t like to suffer, the showers I take are lukewarm, but I enjoy changing my nature (originally fearful and lazy), twisting myself like a piece of wire to give it the desired shape.

To avoid misunderstanding, I want to make it clear that feelings of disgust, pain and fear are not to be fought, for they are necessary for life — so many spiritual authorities blame fear: this is a serious mistake. But they must be controlled and seen for what they are, which are automated chemical processes designed to protect us.

We should make ourselves as aware as possible of the emotional mechanisms that tend to rule us, to prevent us from living a life of silly reflex behaviours.

In the ritual, a woven glove (or gloves) is filled with stinger ants & the participant must wear the glove/s on their hand/s for at least 5 minutes. With the stings from the ants creating temporarily paralyses of the hand/s and arm/s, whilst also causing the participant intense pain &, often leading to hallucinations and shaking.

You were born in Florence, from an Italian father and a Hungarian mother, as a Jehovah’s Witnesses. When your parents divorced, you immigrated to France with your mother when you were a young child.

How do you think the Jehovah’s Witnesses upbringing has impacted your life and your art?

When, at the age of fifteen, I decided to baptize myself as a Jehovah’s Witness (no one is born a Jehovah’s Witness), it was motivated by a desire to attend the destruction and slaughter of the Battle of Armageddon (in particular, the crushing of children under the weight of collapsed architectural elements), as well as the assurance of a life that would last forever.

But a few months later, a friend gave me to listen to Sex & Violence by The Exploited (the live version of this song, recorded in 1981 at the Nite Club in Edinburgh, on the album On Stage), and this association of ideas resonated within me as something eminently cozy, appropriate to my person.

I told myself then that an eternal life locked up on Earth with only Jehovah’s Witnesses would be hellish, and gave up on Heaven. Since then, the prospect of death, of my death — as a definitive and irremediable end — has been omnipresent for me because it came unexpectedly. I grew up convinced that I was not concerned by such an infamous outcome.

Moreover, suddenly delivered from the religious Evil — and critical towards the Evil established by the laws of Men, thanks to my philosophical readings —, I became godless and lawless to an extreme point, much more than if I had never been a Jehovah’s Witness.

Circa 2003.

Describe some of the things you have done?

I climbed a 6,000-meter high volcano in smooth-soled shoes, voluntarily without food or even water, narrowly escaping death by hypothermia.

During a concert, opportunistic and creative, I drew on the floor, on the white tiles, a 1.5-meter (5 ft) long cock of blood, adorned with balls, using my bumped nose as a brush.

I walked 153 km (95 mi) in 3 days on a partially flooded Salar of Uyuni, voluntarily without taking anything to eat but involuntarily wounded in the foot, incurring the amputation of one of my toes.

I filled my nostrils with shit.

For more than three months, I played with and against one of the four teams of Calcio Storico Fiorentino, a centuries-old tradition of the city of Florence, trying to be selected for the annual tournament of this ball game considered the most violent in the world (one of the reasons I wasn’t chosen was because of a rib broken by one of my teammates during our training sessions.)

Hired as a mortician, I was allowed to handle dozens of corpses and thus become familiar with the smell of death.

In a dark magical forest located at the foot of a sacred mountain, I had the privilege of witnessing the many possessions, sometimes bloody, of a night of worship dedicated to the Venezuelan voodoo entity María Lionza.

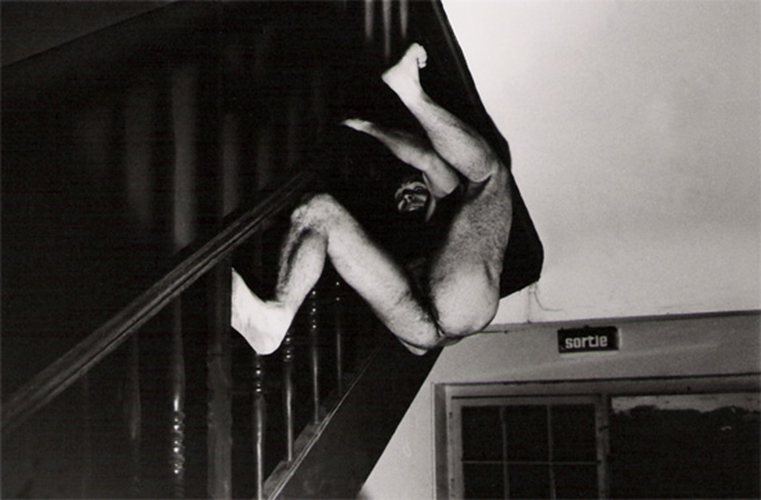

Circa 2010.

Could you say a few words about your book of many pages?

It is an imaginary diary entitled “Outrecuidances Within the Crotch of a Desperation” and written by my pathological double, a fictitious character who is homonymous to me and whose narration is fed by certain pages of my life.

This one is racist, negationist, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, fatphobic, speciesist, misogynistic, ableist, nationalist, conspiracy-theorist, phallocrat, paedophile, omnivorous…, but also has good sides and, what makes him pernicious, is that he is endearing.

In spite of all that he is, the reader risks becoming attached to him and, worse, at times, identifying with him.

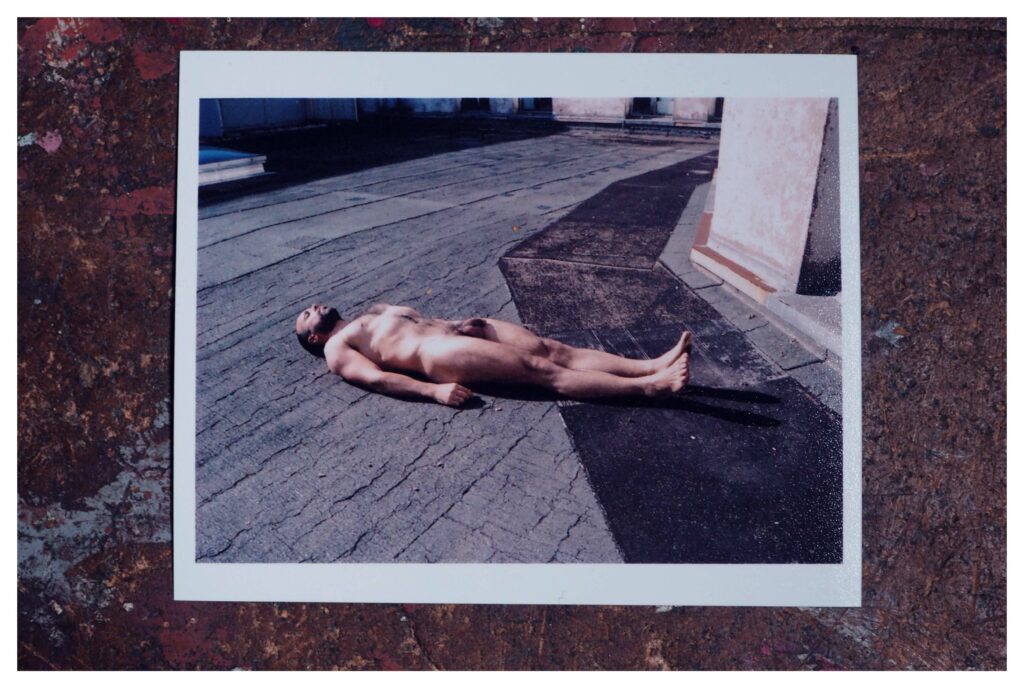

Circa 2015.

Could you tell us of some artists, musicians, authors… that have inspired you?

Trey Spruance, John Zorn, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Henry David Thoreau, Richard Francis Burton, Mike Patton, Henry Miller, Antonin Artaud, Henri Laborit, L’Homme du commun à l’ouvrage by Jean Dubuffet, The Sickness Unto Death by Søren Kierkegaard, Mars by Fritz Zorn, Steve Austin from Today Is the Day, Keiji Haino, Adriano Celentano, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, Jean-Louis Costes, Swift Treweeke, Arnulf Rainer, Georg Baselitz, Vito Acconci, Roberto Benigni, the album Disco Volante by Mr. Bungle, Dennis Cooper…

Circa 2004.

What advice would you give to a debutant artist, let’s say, to an early you?

To speak of “beginning artist” is meaningless. “Artist” is not a profession, but an intrinsic disposition that has no beginning or end. An artist is a shaman — if he is not, he is only a craftsman.

But here is a piece of advice for an “early me”:

“Start by killing your father. Before you become criminally responsible — in case you get charged.”

Circa 2017.

Today, could you say is it worth the trouble, and what’s the use of making art in today’s context?

Since I stopped studying art in 2000, the art that the galleries that matter choose to promote is moralistic, supposedly humanitarian, contributing more than ever to an ambitious social engineering enterprise aimed at creating the new man that the high spheres of finance dream of.

The art that is mine — metaphysical and formalist — has therefore become totally outdated, pathetic, anecdotal, dilettante and, consequently, unfit to be exhibited and sold within the ‘major league’ of the contemporary art network.

Most of the art that today is prized is ethical, or else it is intellectual antics devoid of viscerality.

But for me, it is out of the question to adapt mine to the demand.

I will not put it at the service of an ideology and purposes other than my own, I will continue to devote myself to exactly what matters to me, without worrying about the probability of being praised one day.

I am conscious that it is since the advent of the abstract art, that useful idiot of the most sordid capitalism, art worked to the liquidation of the traditional morals, which opposed a resistance to the progressivism by celebrating values out of the market logic. The first objectives having been reached (‘deconstruction’ — demolition — of the old values in order to make space), this, partly thanks to the validated art of the twentieth century, other objectives have been established (the settlement of a new morality, it, perfectly compatible with the neoliberal optics), attainable with the help of an ersatz art that has neither near nor far to do with my obsessions and relegates to the distant suburbs my art, possibly opportune in the years ’70 to 2000, but, in the twenty-first century, totally useless to the coercive cause of the stealthy supranational intercontinental powers.

I never ask myself if it’s worth it, or what’s the point of continuing, because I am the most eminent customer of my art and in spite of everything, I have to please myself.

With Gyula noting how it, “enabled me to sleep a bit on the second night of my 3-day crossing on an empty stomach of the 153 km of the Salar de Uyuni (East to West).

I was able to sleep snuggled up against this tomb emerging from a Salar flooded by 8 centimetres of water.

You are currently in India.

What are you doing there?

I try to get human flesh.

I don’t want to die without having experienced its taste.

Having ruled out the option of murder, I stay in a city, Varanasi, where, although the practice is not legal, there is a certain tolerance towards cannibalism — as long as it is occasional, discreet and related to autochthon religious beliefs. Because the members of the notoriously cannibalistic Hindu sect of the Aghori are a bunch of real pains and I would therefore prefer to avoid resorting to their complicity, I reside two hundred meters from the open-air crematorium of Manikarnika, on the Ganges, a river whose banks I follow downstream in the hope of spotting some piece of human corpse not entirely charred, thrown into the water by the Doms, a subcaste of Untouchables in charge of the management of the burnings.

Tell us 5 things that matter to you, and 5 things that don’t matter.

Things that matter to me:

1) Prestige

2) Power

3) Not having my shirt stained with traces of food that has fallen from my lips or cutlery

4) Protecting myself by possessing money

5) Being in a position where I don’t necessarily have to be likeable

Things that don’t matter to me:

1) Knowing the meaning of my life, if any

2) Feeling useful

3) The third thing on that list, so much so that I won’t bother mentioning it

4) Being gentle on your sensibilities

5) Appearing cool.

Done, “in an attempt to get blood flowing into my anal sphincter and speed up its cicatrisation.”

Undertaken in Tuscany, Italy.

Circa 2017.

Circa 2018.

Complete this phrase : “I would rather [????] than [????].”

I’d rather upset you than disappoint myself.

Links

- Gyula Noesis – Website

- Gyula Noesis – YouTube

- Gyula Noesis – Instagram

- Gyula Noesis – Facebook

- Gyula Noesis – Email: contact@gyulanoesis.com

- Gyula Noesis – 2019 article by Gyula on his adventures in Brazil, published via ‘Vice’

- Gyula Noesis – Video from his 2003 tour with Jean Louis Costes, performing ‘Holy Virgin Cult’

All images supplied by Gyula.