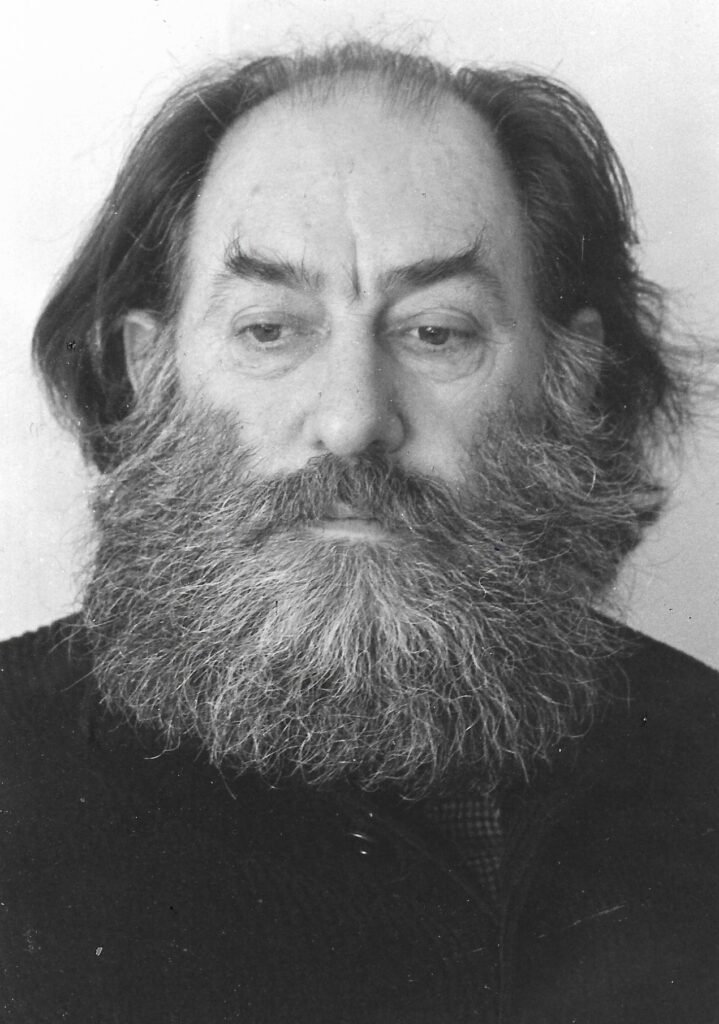

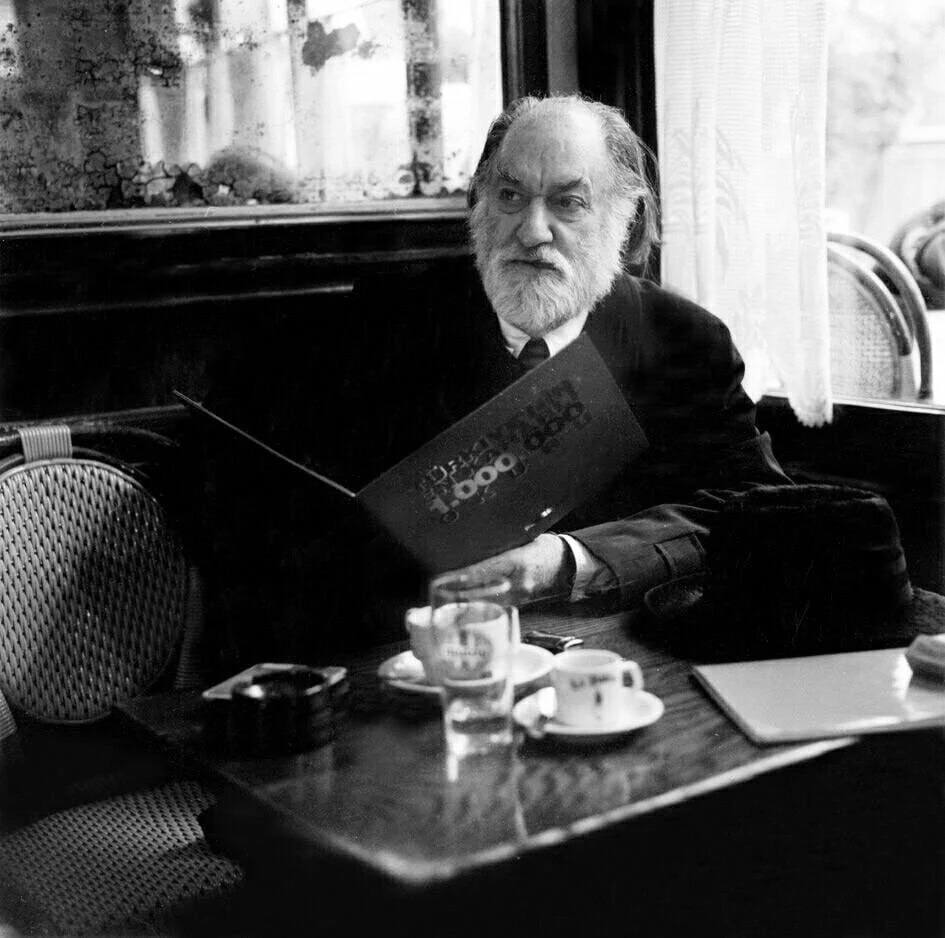

For a Greek readership, no special presentation would be needed for Elias Petropoulos (1928-2003), the famous, indeed in some circles still-notorious Greek poet, writer and “urban folklorist.” Yet probably only a few English-language readers will be aware of the numerous accomplishments of this exceptional author who, “had he not been such a naughty mounopsira, a ‘woman’s crotch louse’ – as the expression goes and as he liked to characterize himself -digging down into fine details and pinching the Greek state and establishment where it hurts, he would have been celebrated as a national treasure.”

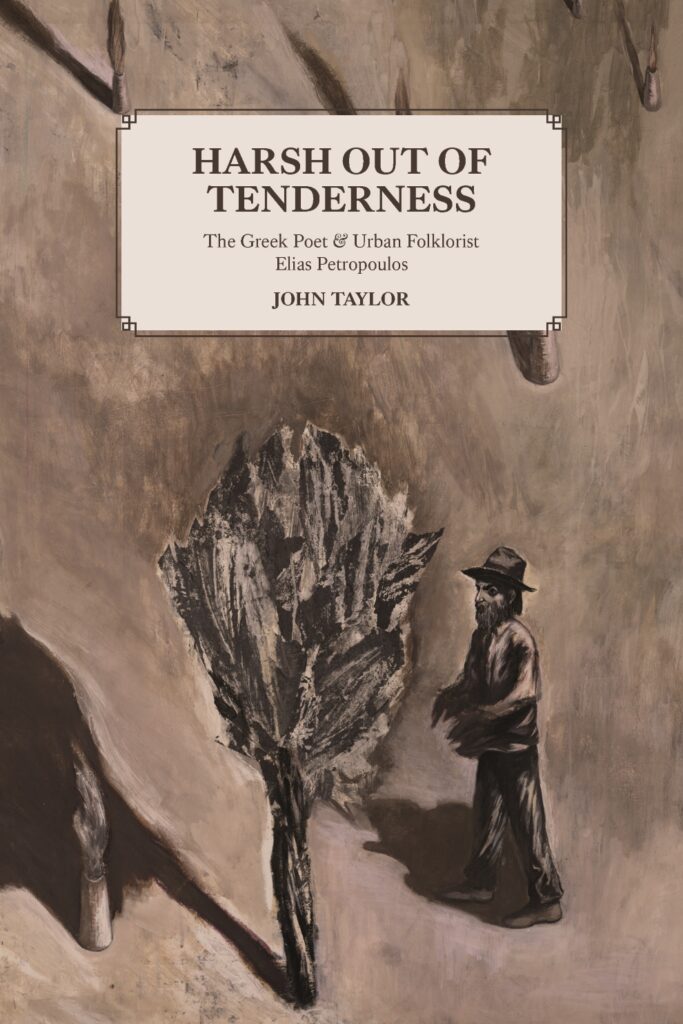

So states the American writer John Taylor in his preface to ‘Harsh out of Tenderness’, his remarkably insightful, informative and vivid memoir of working with Petropoulos as his translator, especially in Paris in the 1980s but also later. Taylor is absolutely right in his appraisal. Shrewd, perceptive and extremely multifaceted as a creative writer and independent researcher, Petropoulos meticulously tackled a wide range of topics in order to elucidate cultural and sociological realities which were overlooked in his day and which today, thanks to his writings, now seem evident.

As Taylor puts it, the Greek writer, “produced a multifarious, groundbreaking, and oft-humorous literary, lexicographical, and folkloristic oeuvre that consistently provoke – and still provokes – extreme reactions from his readers. One intensely admires Petropoulos, or despises him; dispassionate appraisals are rare, almost excluded by definition. This is to say the least, but the purpose of [my] portrait of the author is, of course, to get beyond this ‘least.’”

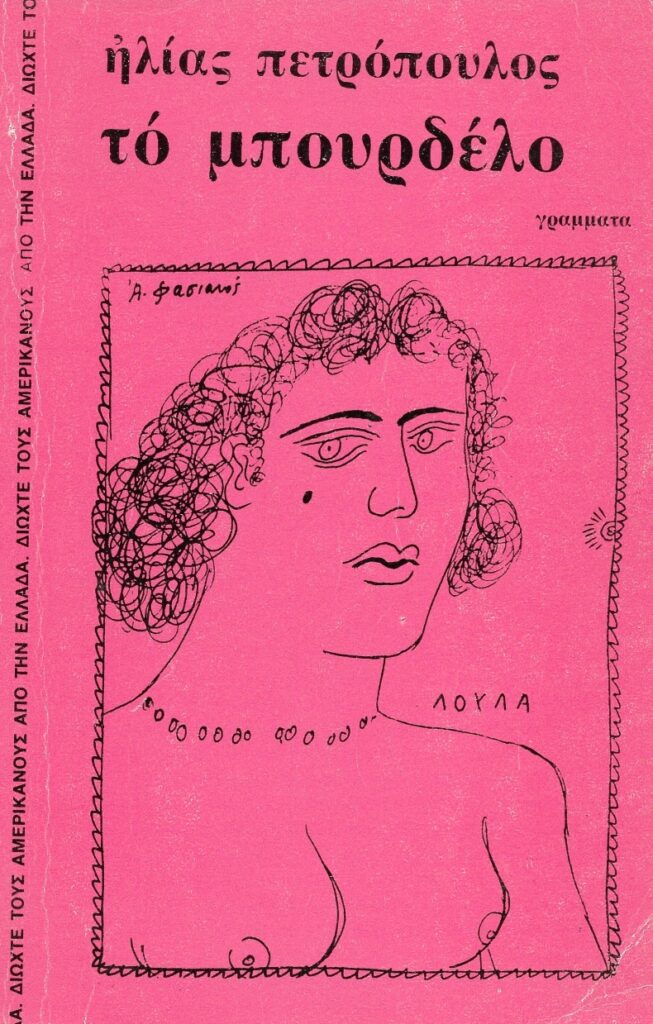

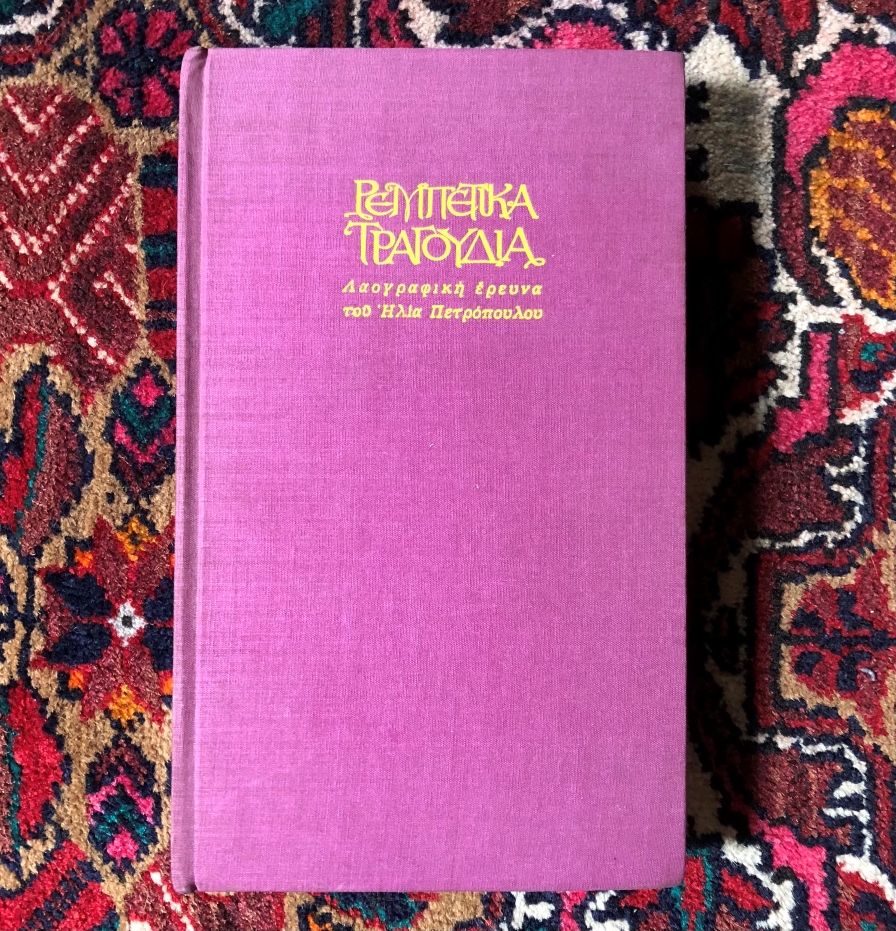

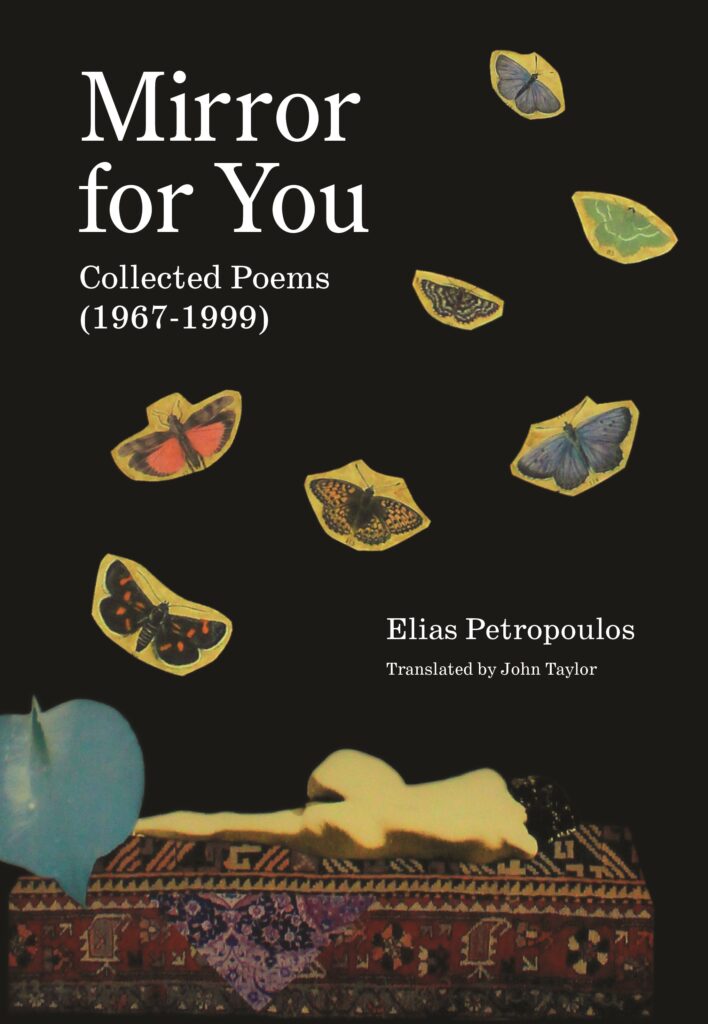

Petropoulos’s pioneering books indeed delve into subject matter ranging from prison life, public hygiene, sexual mores, marginal subcultures, and the sociology of marketable love; to hats, moustaches, newspaper stands, graffiti, folk architecture, and gravestones. Some of his best-known titles are ‘The Good Thief’s Manual, Rebetika Tragoudia’ (his anthology of the uncensored lyrics of the underworld “rebetic songs” that one still hears as background music in Greek restaurants), ‘The Brothel’, ‘Kaliarda’ (his lexicon of Greek homosexual slang, in fact the first such dictionary published anywhere in any language), ‘Turkish Coffee in Greece’, and ‘Greek Cemeteries’; not to forget his poetry, which has also now become available in English, in Taylor’s translation, as ‘Mirror for You: Collected Poems 1967-1999’ (Cycladic Press, 2023).

In fact, Petropoulos first and foremost considered himself a poet (who was often an erotic poet). It is in his poems that his otherwise oft-concealed sensitive side shows through:

“You want me to be sincere in my writing.

My most beautiful love letters

Are these little poems that I jot down. . .“

Featuring art by Alekos Fassianos.

For one long-poem, Body, and two of the aforementioned books (the rebetic song anthology and the gay slang lexicon), Petropoulos was imprisoned three times in Greece during the dictatorship of the Colonels (1967-1974), and he was even sometimes persecuted by judges as late as the 1980s, notably for ‘The Good Thief’s Manual’, his perfectly practical “enchiridion” based on what he had learned by conversing with common criminals while he was himself in prison.

But by 1975 he had gone into exile and settled permanently in Paris with his partner, the excellent folklorist Mary Koukoules. He never returned to Greece. During the next three decades, Petropoulos never ceased pestering the Greek establishment through his countless articles and nearly eighty books.

In Harsh out of Tenderness, Taylor translates numerous excerpts from these books to enable English-language readers to grasp the groundbreaking importance of this vast oeuvre that consistently shows an untameable curiosity about others and otherness.

Born in Athens but then raised in multiethnic pre-World War II Thessaloniki, Petropoulos indeed showed a deep interest in, on the one hand, the Ottoman and other Balkan influences on modern Greek culture, and, on the other hand, the history and everyday life of the large Jewish community which, over the centuries, had played a major role in the city.

He was, moreover, the first person, already in the early-1980s, to raise the public issue of the need for the Greek state to officially recognize the genocide of the Greek Jews during the Occupation. Petitioning the Greek government to this end, he likewise criticized the attitude of many Christian Greeks who, back then, either had shown indifference to the plight of the Jews or had silently consented to their deportation to Auschwitz and hastened to profit from the Nazi pogroms waged against them.

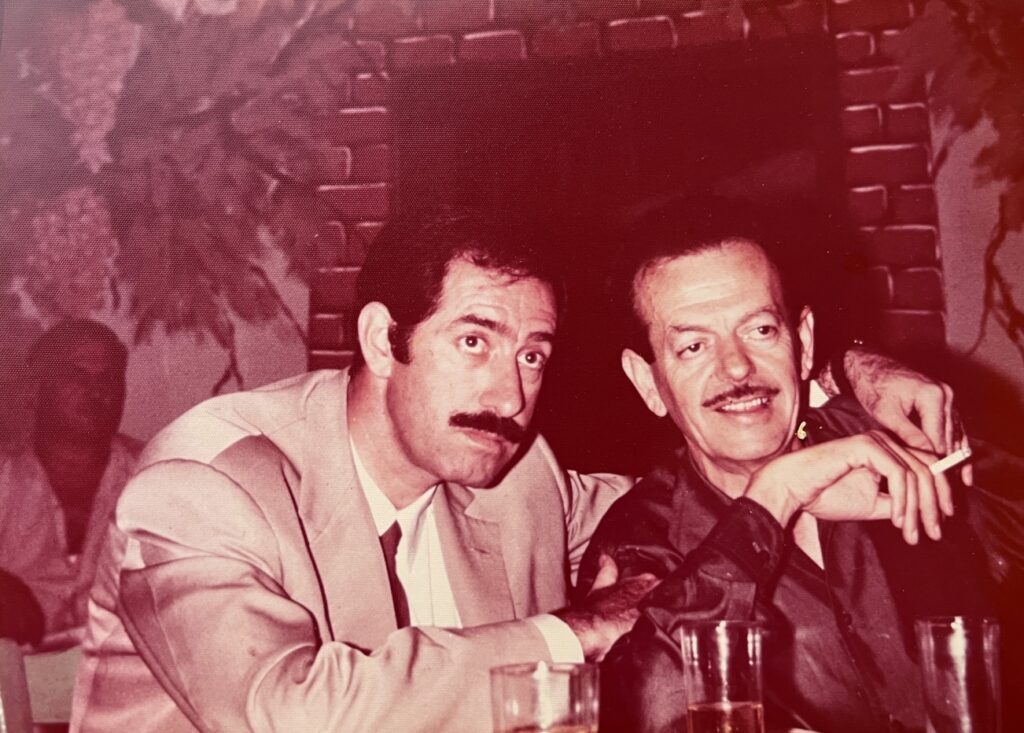

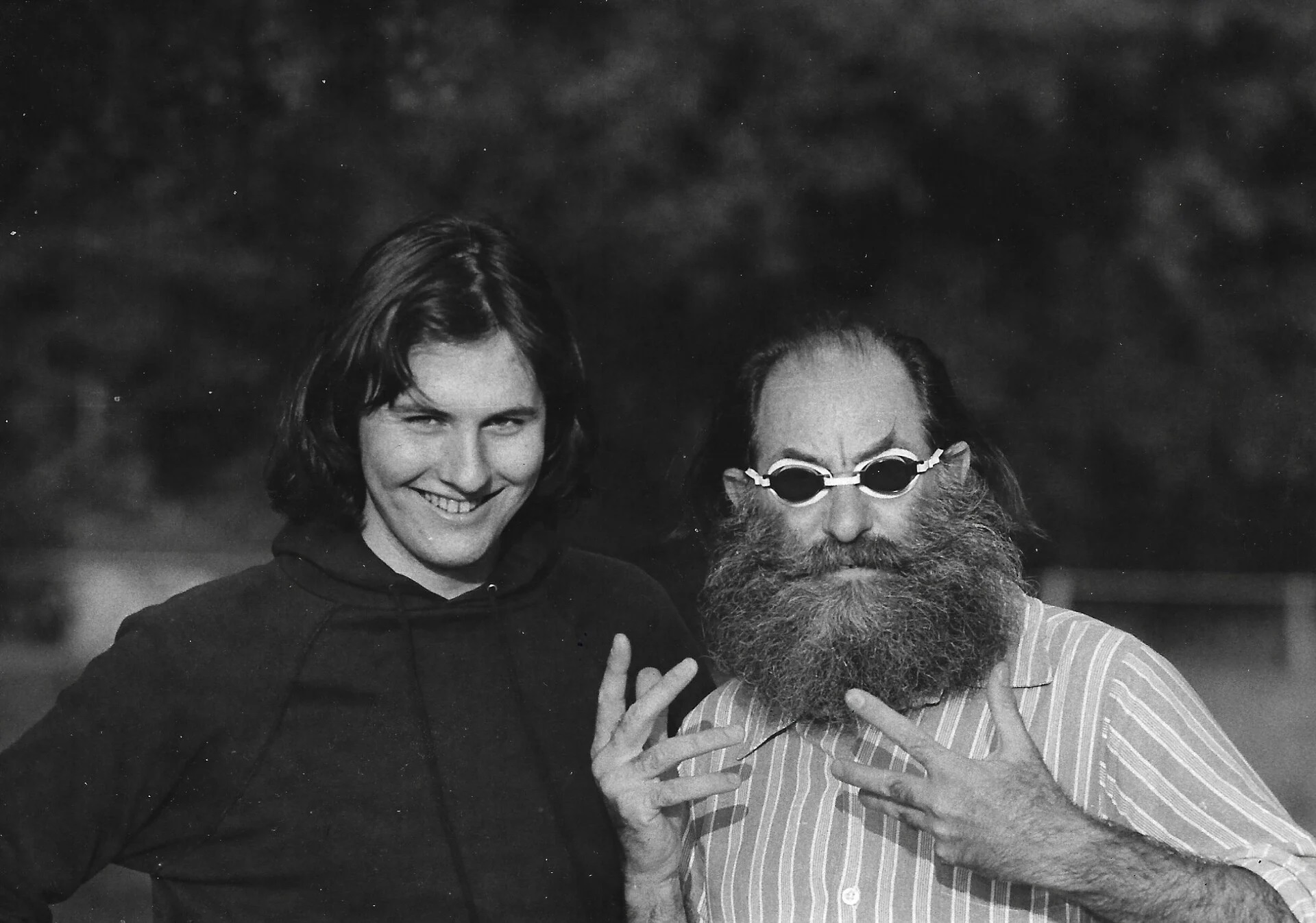

In the City of Light, in 1979, Petropoulos met Taylor by chance. At the time, the then-young American prose writer, poet, and literary critic had himself arrived in Paris two years beforehand, after living in Greece for a year.

Taylor recounts this decisive and amusing stroke of luck. He became Petropoulos’s translator, also a kind of English-language secretary for him, and accompanied him on various errands and strolls, which included work sessions, in a high-quality printing shop, on the author’s self-published bibliophilic editions of his poems and of various books put together as tributes to the Jews of Thessaloniki. The two men became close friends within the context of a “teacher-student” or “mentor-apprenticeship” relationship, as Taylor describes and details it. Taylor is therefore one of the very rare writers to have known Petropoulos so well and to have glimpsed more secret, sensitive, aspects of his character that were little-known, if at all, to Greek readers fascinated (or infuriated) by the author’s provocative writings and acts.

Photo by Vassilis Liappas.

Beginning only a few days after Petropoulos’s funeral (at the end of which, according to his wishes evoked in a poem, his ashes were scattered in a Paris sewer), Taylor felt a deep necessity, akin to a duty, to write this “insider’s portrait” in honour of his friend and mentor who was at once “tender, generous, melancholy, and full of a rage that kept him looking hard at the world, and at words.”

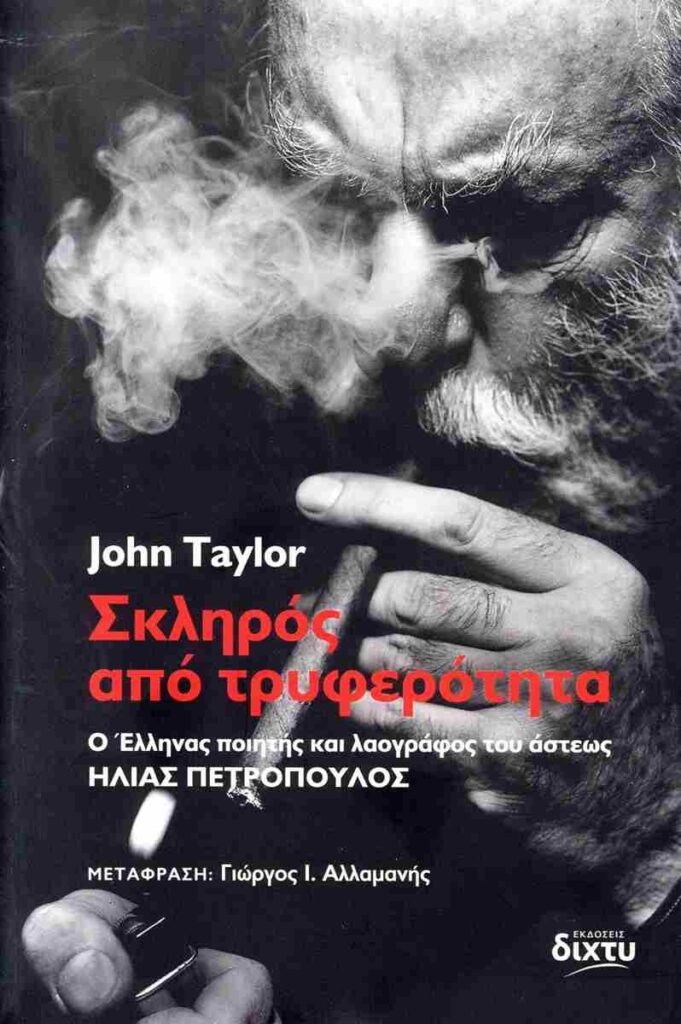

‘Harsh out of Tenderness’ was originally published in English in 2020 by Cycladic Press and has now been translated into Greek, by Yorgos Allamanis, and published by Dicty Editions in Athens to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of Petropoulos’s death. This Greek edition, which has met with much acclaim in Greece, has given me, the opportunity to ask John Taylor some questions about how he remembers Elias Petropoulos.

If someone were to ask you how important a personality you consider Elias Petropoulos to be and why, what would you answer?

John Taylor: As an “urban folklorist,” as he liked to call himself, Elias Petropoulos played an essential role in twentieth-century Greek culture. Obstreperous, refractory, bold, and courageous, he was a brash iconoclast but also a serious and rigorous pathbreaker who shook up preconceived ideas overly fashioned by nationalism and prudishness.

Specialized in “marginal topics,” some of which were initially considered to be insignificant or shameful, he remains an author whose books are a delight to read because of their uncompromising exactitude, original first-hand information, sardonic humor, lively descriptions, while the whole is often graced with drawings and photos.

Petropoulos put his finger on the truth, or simply on reality, more often than many of his contemporaries claimed during his lifetime.

What is it that you hold most dear from your interaction with him?

How would you characterize him, what do you consider to be his greatest gifts and what possibly were his drawbacks?

J.T.: Elias Petropoulos and I were very different in our respective literary aims, tastes, and sensibilities. A reader who chances upon my other book available in Greek, ‘Portholes‘ (Koukkida Editions), which is a sequence of interconnected poems drawn from my longer American book ‘Grassy Stairways‘ (The MadHat Press) and set on a ferryboat crossing the Aegean Sea, will perceive this immediately.

A passage towards the end of Harsh out of Tenderness, my book about Petropoulos, indeed begins: “He was an unlikely teacher, I an unlikely pupil. So much separated us, or should have—but did not.”

When I think back on our friendship and professional relationship, and how they affected me in various ways, I remember these stark differences most of all. For example, Petropoulos could stare hard at brute facts, meticulously examine objects from all angles, immerse himself in the outside world. As a young poet and writer, I was much more subjective, introspective. In order to grow as a writer, I needed to have this aspect of my literary personality challenged.

Taking a stroll with Petropoulos in Paris or in the forest near his country home in Coye-la-Forêt was always an exercise in learning how to see sharply.

In this respect, what Petropoulos taught me most deeply was how to look objectively at the outside world. Yet this is not to suggest that he was himself not introspective. Many of his poems reveal his tormented, melancholy inner world.

He could be hardheaded to a fault, but he was also secretly sensitive and even sometimes shy.

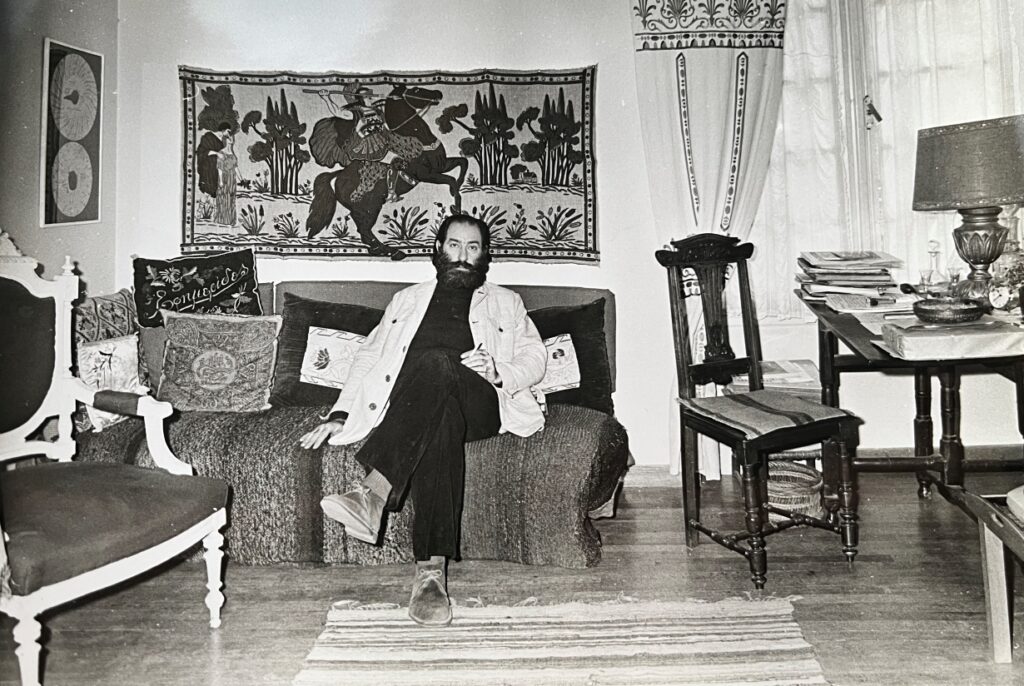

Photo by Vassilis Liapas.

Which person(s) and which life experiences would you say marked him the most?

J.T.: Two experiences stand out. He mentioned them often.

The first was the probable death of his father during the Second World War. His father, who like Petropoulos was also a member of the Greek Resistance movement, had first fled to Albania and then, in 1944, disappeared, probably murdered. However, the corpse was never found and, although Petropoulos later had a few leads and hypotheses, he was unable to elucidate the mysterious circumstances under which his father, aged forty, had vanished forever from his life. In his poetry book, ‘After’, he evokes his “unbearable melancholy / that has haunted [him] ever since ’44.”

The second decisive event was his encounter with the writer Nikos Gabriel Pentzikis. Petropoulos met Pentzikis as early as 1948 or 1949. Pentzikis became his mentor.

Petropoulos’s first book, a pioneering study of Pentzikis, dates to 1958, and he was one of the regular visitors at the famous pharmacy in Thessaloniki in which Pentzikis distributed many more literary insights than pharmaceutical drugs. “Pentzikis showed me how to use my eyes,” wrote Petropoulos, “slowly but surely I learned how to see things askew, diagonally, illogically, axonometrically, unorthodoxly.”

When I visited Petropoulos in the clinic shortly before his death, to say farewell to him, I repeated his words about Pentzikis to him, telling him that I had been taught the same kind of multiplicitous vision by him.

Is there any particularly memorable incident (or perhaps more than one) related to your acquaintance with Petropoulos?

J.T.: Being with Petropoulos even in completely ordinary situations, such as discussing a translation with him in his apartment, was often memorable not only because of what he said, but also because of his particular and very professional way of working.

He was rigorous and exacting, in fact a maniac about all the practical aspects of writing. He despised Bic pens, for example, and insisted that I use the high-quality felt-tip pens with which he himself wrote. To drive his point home, he offered me a few such pens in various colors so that I could correct my manuscripts and galley proofs in different ways.

Let me cite one event that recurred rather often. We would go together to the Mérat Brothers’ printing shop on the rue du Vieux-Colombier (famous for its association with Antonin Artaud) to finalize the bilingual bibliophilic albums that were printed there. We would spend the entire day in the shop.

These work sessions took place in the 1980s, before the widespread use of computers, and the Mérat brothers knew how to print books with great care, à l’ancienne. It was at this printing shop that Petropoulos taught me, with his hawk’s eye, to correct proofs meticulously. Sometimes a comma would need italics, or not, and we would examine every single one of them. He would go over the page layout centimetre by centimetre, varying the position of photographs on the page, for example, to keep his book from appearing dull and monotonous.

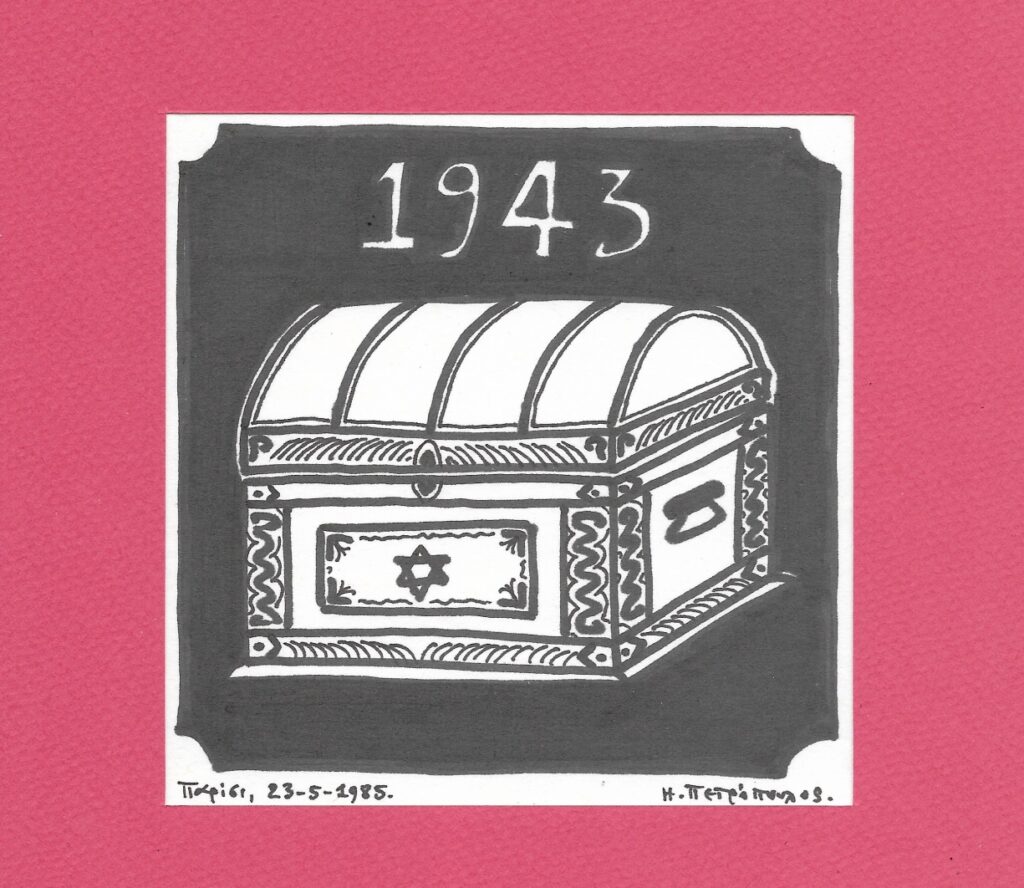

He loved refined printing and elegant paper, especially thick Arches paper. Moreover, Petropoulos never wasted paper. At the printing shop, he would keep anything and everything that had been discarded by the Mérat brothers during experiments with shades of ink or when pages were measured and cut. He would use these pieces of scratch paper in various ways, sometimes for his drawings, at other times as supports for his erotic collages or his holiday greeting cards.

No one ever sent me more holiday greeting cards than Elias Petropoulos. He sent them to countless other friends and professional contacts as well. I must add, however, that some of these holiday greetings were pranks “signed” by someone else, either living or dead, either imaginary or real.

Published in 1968.

Of the many books that he authored, which do you consider to be the most significant?

J.T.: The anthology of rebetika (underworld rebetic songs) and Kaliarda (the dictionary of Greek homosexual slang) are fundamental works that can be ignored by no contemporary researcher in these fields.

The several shorter books and photograph albums dealing exclusively with, or partly with, the influence of Ottoman culture (and other Balkan cultures) on Greek everyday life and language – Turkish Coffee in Greece being the most emblematic of these studies – and the other texts or books detailing the mores and customs of the Greek underworld (hypokosmos), all form a rich and varied corpus that shifts and sometimes overturns how Greek culture and “Greekness” are viewed.

At a recent academic conference devoted to his work, at the Villa Kerylos in Beaulieu-sur-Mer, I was able to measure the extent to which these pioneering books have stimulated younger scholars who were sometimes mere youngsters or students when Petropoulos died in 2003 and who now explore the same fields by benefitting from the epistemological refocus that he introduced. Such books were controversial when they first appeared, and were often summarily rejected, but Petropoulos had outlined cultural and sociological truths and realities that now seem evident.

His insistence on the overlooked importance of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki is a similar case in point.

However, we must remember that Petropoulos considered himself principally to be a poet. Recently, my translation of his collected poems was issued under the title ‘Mirror for You‘ (Cycladic Press, 2023).

While working on that book, which involved rereading my earlier versions from the 1980s and translating later books that I had never rendered, I was struck by how much of himself Petropoulos put into his poems. I am especially thinking of his books ‘After’ and ‘Never and Nothing.’ The short, direct, thought-provoking pieces in those two volumes often epitomize the aphoristic qualities already present in the equally important long-poems Body and Suicide.

Moreover, I would like to suggest that there is a kind of unity between the folkloristic writings and the poetry. This unity can best be discerned in the arresting melancholy informing both kinds of writing.

Even in his prose, Petropoulos never conceals his personality, or his subjectivity, behind the multitude of objective facts that he catalogues or describes.

Translated into English by John Taylor.

Published by Cycladic Press (2023).

What if I told you to pick out one poem, or lines of a poem, written by Petropoulos?

J.T.: When I was writing my memoir, one quatrain, comprised in Never and Nothing, kept haunting me.

I ended up borrowing it for my title because it sums up Petropoulos so well:

You ask me

—why are you so harsh?

I answer:

—out of tenderness.

How do you explain the fact that instead of leaving Greece during the Junta, as many intellectuals did – especially given the fact that he himself had been censored, even imprisoned – he decided to emigrate as soon as democracy returned?

J.T.: Petropoulos was imprisoned three times during the Junta, for his anthology of rebetic songs, for his dictionary of Greek homosexual slang, and for his long-poem Body. He had the courage to self-publish those books during the dictatorship and he knew all too well what the consequences would be.

During those dark years, I doubt that he had the financial means to emigrate. It is also likely that he considered that it was his duty, as a writer, to remain in Greece and defy the Colonels with his publications. In any case, he had firmly resolved to publish books that he considered fundamental.

Towards the end of that period, his encounter and subsequent amorous relationship with Mary Koukoules enabled him to emigrate to France, where Mary already lived part of the time. Her personal wealth and moral encouragement enabled him to continue to write his oeuvre exactly as he intended it to be written and to publish exactly what he wanted to publish.

Her role, both practically and intellectually, was essential.

How did his particular sympathy for Jews and Turks come about?

J.T.: Petropoulos was born in 1928 in Athens, but he was raised in Thessaloniki after his father, who was a minor civil servant, was transferred there in 1934. As fate would have it, his parents settled in a house formerly owned by a Turkish bey.

Petropoulos was fascinated by the multiethnic ambience in Thessaloniki and immersed himself in it. He had childhood playmates from within the Jewish community, notably a close friend named Samiko who was later, in 1943, like nearly all the Thessaloniki Jews, deported to Auschwitz and exterminated there.

The loss of Samiko affected him deeply, for his entire lifetime, and he evokes this in A Macabre Song. Petropoulos also wrote a touching and revealing text about his love for his mother’s Jewish seamstress, whose name was Allegra.

Beginning with those formative years, Petropoulos remained animated by a genuine affection for, and attraction to, people quite different from himself in ethnic origin and lifestyle. He was attentive to otherness, especially marginalized otherness.

He was also curious about homosexuals, indeed drag queens, about Gypsies, and about underworld figures such as manges. His inclination was to understand them before judging them and, if necessary, to defend them through his writings.

Given his own inner torment resulting from various misfortunes and tragedies in his life, namely the loss of his father as well as the death of dear friends in the Second World War and the Greek Civil War, I would hypothesize that his interest in social outcasts also enabled him to project his thoughts, emotions, perceptions, and analyses into others, and therefore temporarily beyond and away from his own self.

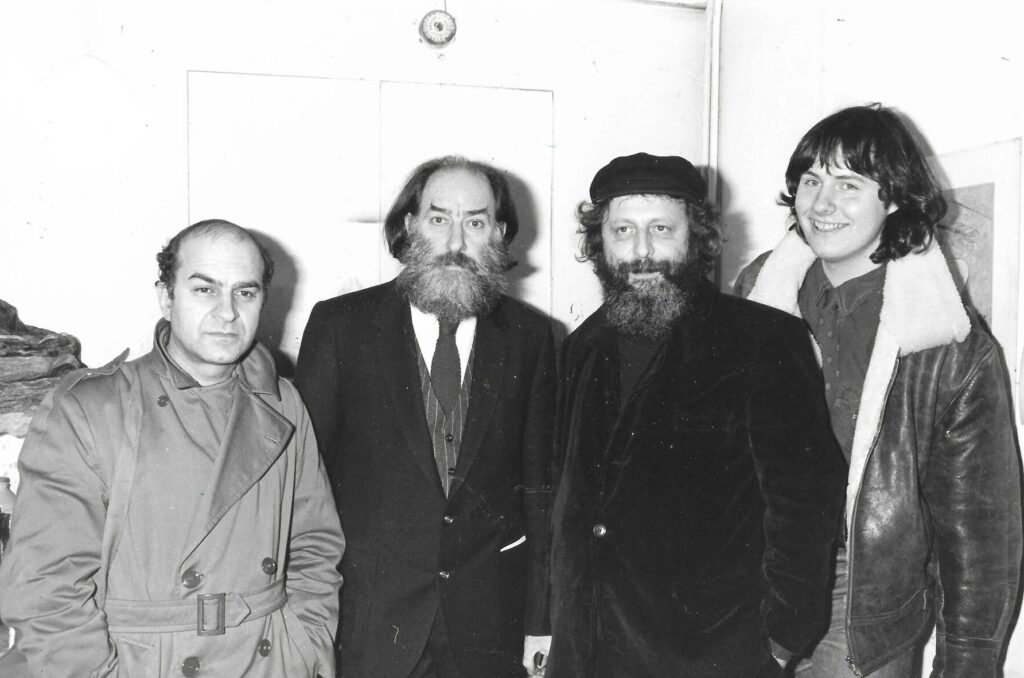

Enjoying themselves at a bar during the 1960s.

Is it true that with France and the French he maintained a “love-hate” relationship?

For Americans like you, what feelings did he have for them?

J.T.: “Love-hate” is not exactly the right adjective. In my book, I describe several examples of his complex relationship with the French and try to give nuances to the unease, anger, and misunderstanding sometimes, but not always, felt by Petropoulos in France.

He was forty-seven years old when he arrived in Paris with Mary Koukoules. He knew no foreign languages. At that age, it is not easy to learn a new language, let alone insert oneself fully into a foreign society. However, Petropoulos did slowly but surely learn French and he was by no means isolated in Paris. Through Mary and others, he met artists, writers, and intellectuals, some of them Greek, others foreigners like himself (and myself).

When he became friends with Jacques Vallet, the editor-in-chief of the art-and-literary magazine Le Fou Parle, in the early 1980s, he met still more artists and writers, many of them French. This being said, these friendships did not enable him to get his books translated into French, with the exception of an edition of his poems, prefaced by the poet, writer, and translator of modern Greek literature Jacques Lacarrière, who was, moreover, one of his very first French friends.

After self-publishing a few bibliophilic books in French translations before he met me, Petropoulos went on to self-publish several of his books in bilingual Greek-English editions, taking ferocious pride in the fact that “printing texts in English in Paris gives the French a good slap in the face.” Yet it must be kept in mind that the topics of his folkloristic books were very Greek, too Greek as it were, to interest most French publishers.

I would say that Petropoulos remained secretly frustrated by the fact of not being published in French, but that he was too proud to admit it and not flexible and patient enough to enter into dialogue with a French publisher who might well not be initially aware of the originality and quality of his books and of his fame in Greece.

In any event, his attention was drawn to at least one French topic, the weathervanes placed on the roofs of houses. He did some research on this subject matter and took several photos of weathervanes, once in my company; but this project was never realized. He was also interested in French tombstones for a while and had a liking for the little plaster dwarfs (“nains de jardin”) that the French place in their flowerbeds and vegetable patches. ?

My own situation was very different. I quickly became fluent in French, my wife was French, and I was fully integrated into French life. Nor was I a typical American. I already knew three foreign languages when I met Petropoulos and, although I was (and remain) an American writer who writes in English, I was above all interested in European literature. Petropoulos disliked American politics, to say the least, but he appreciated some aspects of American culture and literature. One was his three favorite books, as he recalls in In Berlin, was Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. (The other two were The Iliad and Casanova’s Memoirs.)

Did Petropoulos talk to you about other modern Greek authors?

J.T.: Indeed he did. He wanted me to read writers whose themes or styles would interest me because of my own literary goals and preferences. Thanks to him, I became acquainted with Elias Papadimitrakopoulos’s stories, which I ended up translating and which had an essential influence on my own prose at the time.

Petropoulos also encouraged me to read the poetry of Manolis Xexakis and Veroniki Dalakoura, both of whom I also translated. He also suggested, in his firm manner, that I discover the work of two former writer-friends with whom he had bitterly quarrelled: Dinos Christianopoulos and Yiorgos Ioannou.

The anecdote involving Christianopoulos is particularly revealing. One afternoon Petropoulos, sitting behind his desk in the living room of the rue Mouffetard apartment, fingered through his address book, found Christianopoulos’s name, and dictated the address to me. “Write to him,” he ordered, “not mentioning my name. And tell him that you are interested in his poetry.” Petropoulos had shown me sample poems from Christianopoulos’s Short Poems, pointing out that the poet had an “extraordinary sensitivity.”

Although many of Petropoulos’ books and publications broke new ground and are considered “one of a kind,” some argue that, towards the end of his life, his investigative spirit gave way to his desire to cause scandal.

They also blame him for not sufficiently substantiating certain conclusions as well as some of his criticisms.

What is your opinion?

J.T.: As I have already stated with respect to the epistemological shift or refocus that Petropoulos introduced into our comprehension of modern Greek culture, it should be kept in mind that his provocative acts and writings were aimed at forcing Greeks to admit to certain truths and to accept certain realities.

Petropoulos relished being in the limelight of controversy and collecting the articles written about his books and acts, but his deepest goal had nothing to do with notoriousness. It was both factual and conceptual as well as poetic.

Several examples of such “scandals” could be given, but the most moving one consists of his efforts to get the deportation and extermination of the Thessaloniki Jews in the Second World War recognized and commemorated by the Greek government and by the Greek people as a whole.

If he ultimately put forth aggressively his “demand” with regard to this issue to the then-Minister of Culture, Melina Mercouri, threatening to sue the government after she did not respond to his initial “appeal,” this was because the gaping postwar absence of the Jews was acknowledged by so few Greeks at the time, not to mention by the authorities.

From John Taylor’s personal archive.

Throughout his writings, Petropoulos’s sarcastic and humorous – this stylistic aspect must not be overlooked – prose served this purpose. He conceived “a book” as “an ice axe to break the sea frozen inside us,” to cite the quotation by Kafka that Petropoulos used as an epigraph for The Good Thief’s Manual.

Moreover, instead of building up his books from the findings of previous scholars (if there were any, which was rarely the case) in the fields of research that engaged him, he relied on his own experiences, on his vast and precise memory, on interviews with living witnesses, as well as on his own collections of first-hand documentation, such as photos and postcards.

He was a relentless seeker of sources, of origins, of unadulterated subject matter, and he staunchly believed that no conclusions could be constructed before the task of documenting a topic had been thoroughly accomplished. And yet, in contrast to this methodology, he would simultaneously and boldly propose hypotheses and raise questions in his texts even when he was in no position to answer them.

In the last decade of his life, I also perceived an ever-greater urgency in Petropoulos, an overwhelming tension driving him to get as much as possible down on paper of what he had long intended to write. This surely explains the impressive number of articles that he wrote for the several magazines which, by then, were giving him a free rein to write about whatever he wished.

But poignantly enough, when he died, he left unfinished the manuscript of The Cemeteries of Greece, the book on which he had laboured for over thirty years and which he repeatedly claimed would be his masterpiece. About seven or eight pages remained to be written. . .

The album was published posthumously in 2005 as ‘Ellados Koimitiria‘, with illustrations by Costas Tsoclis and reproductions of Petropoulos’s handwritten instructions about how it should be printed.

(Still from Kalliopi Legaki’s 2005 documentary, ‘A World Underground‘.)

Links

- Original article in Greek – via Lifo

- Link to buy ‘Harsh out of Tenderness’ (English edition) – via Cycladic Press

- ‘Harsh out of Tenderness’ (English edition), review by Angela Garrick – via The Aither

- John Taylor – Website

Header image shows a young John Taylor, with Elias Petropoulos in 1979. Photographed by Françoise Davies-Taylor.

This interview between Theodore Antonopoulos and John Taylor was carried out by e-mail during the period 18-29 December 2023. It was first published in Greek in Lifo on 7 January 2023.

All images supplied by John Taylor.

![We Chat With John ‘Jughead’ Pierson aka ian pierce – Writer, Thespian, Musician, Podcaster at Jughead’s Basement Podcast; Founder of Hope And Nonthings Theatre Co. & Publishing House; Founding Member of Bands ‘Screeching Weasel’, ‘Even In Blackouts’, ‘The Mitochondriacs’ & ‘Semi Famous;’ & Co-Founder of Record Labels ‘Roadkill’ & ‘Panic Button’ [Yeah, the bloke has done a lot we know!]](https://theaither.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/IMG_7679-sml-352x264.jpg)