Ric Royer (born 1979, in Niagara Falls, NY, USA) is a performance artist, actor, playwright, director, writer, and publisher. He spent much of his early career in performance – his “avant-vaude” collective, Psychic Readings Company (1999), staged experimental theatre pieces, such as ‘Fete of Mistakes’ (Ontological Hysteric, 2014), an adaptation of Jean Genet’s ‘The Maids’ (Secret Robot, 2016), and many brilliant originals by himself and other artists.

He also built a vibrant theatre company and community in Baltimore, eventually renovating two multi-story buildings to house and produce creative and edgy theatrical and musical performances.

My first experience with Ric was seeing him perform ‘The Coincidental Hour’, an absurdist performance art variety show, over a decade ago. Accompanied by his frequent collaborator, sound designer G. Lucas Crane, ‘The Coincidental Hour’ was, “a late-night game show, children’s tv variety show, talk show, cabaret show, and musical twilight zone piece of Vienna Aktionist performance art; with the prizes!” – and I’m happy to report that this is an apt description.

I was immediately compelled by Ric’s ability to squeeze and pull the audience in an accordion of squeamishness and irreverent delight, and I was to learn that manoeuvring deftly from queasy cringe to childlike joy is a powerful through-line seen in many disciplines of his work.

Ric’s creative persona embodies more than a bit of the trickster god, or sacred clown. A cunning being found across cultures and time, the trickster is delightful and frightening in their disregard of common mores, or even the laws of physicality; shape-shifting and deceiving, disarming by disorienting.

Their impish tomfoolery and nose-thumbing at the standards of society belies their dark power and contact with the sacred – there’s a lesson to be learned through their oft seemingly anarchic actions.

[Photo by Dave Iden.]

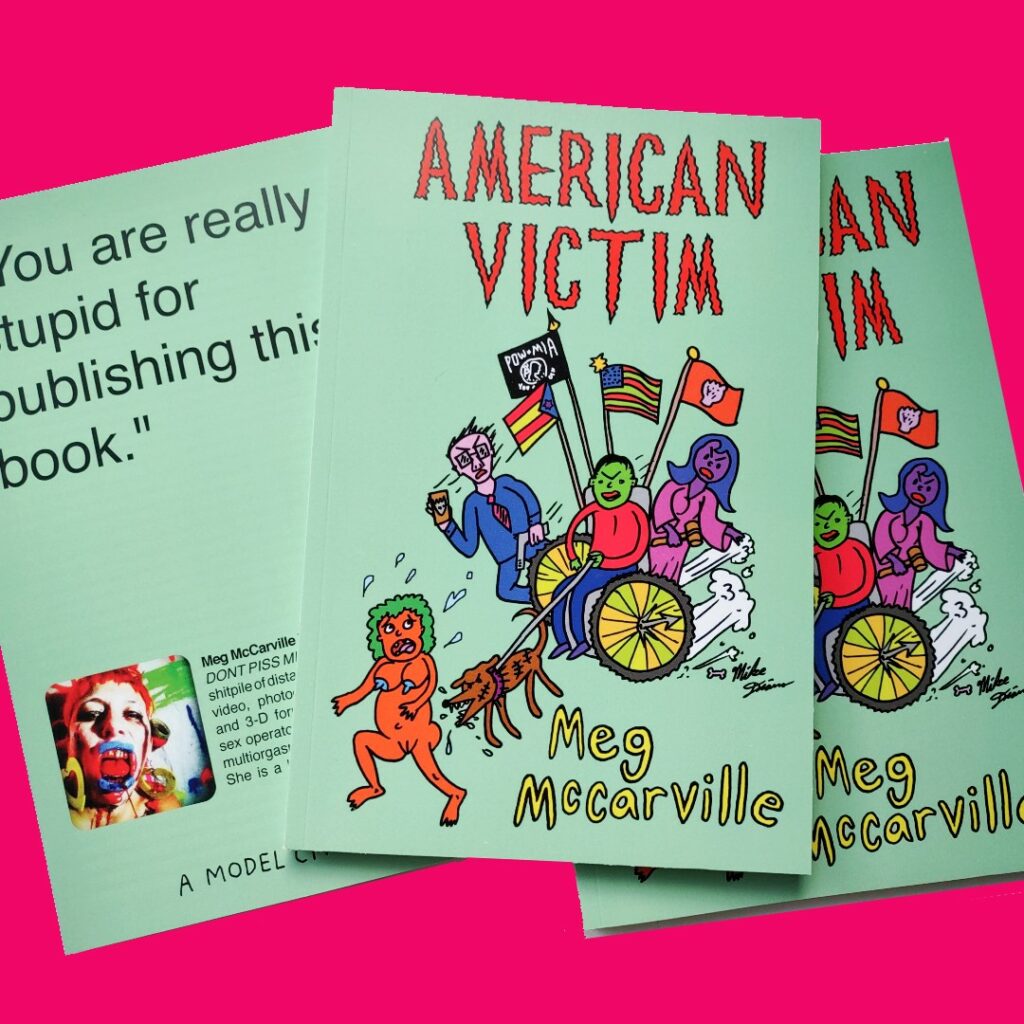

A lifelong writer, in 2019 Ric branched out into publishing, via his imprint Model City Books. With a focus on experiments in prose, poetry, unusual memoir, underground comics and weird concepts; Model City has so far released works by people such as Meg McCarville, Tamas Panitz, and Julia Dzwonkoski.

Late last year, Ric released his first full length novel ‘Niagara Falls, NY’, via underground publishing house Pig Roast Publishing (run by Jeff Schneider.)

A kind-of-a-fiction that reads like a surrealist memoir, it begins with the narrator’s homecoming to Niagara after an unnamed daunting life event. Ostensibly in town to write an article on 19th century utopian developer William T. Love, he finds himself forced to engage with, and re-examine, his dystopian hometown, his family, and his own raw self after a great loss.

Published in 2023 by Pig Roast Publishing.

Ric now resides in the Catskills with his partner, writer Miriam Atkin.

We chatted over the phone about ‘Niagara Falls, NY’, the world in which it was written, and his process.

AG: I want to thank you for the great read.

I’d like to launch into something about this book that really struck me. I know this is something that’s present in a lot of your writing, but there’s a deep, philosophical use of body-horror here. You unabashedly express the grotesque wretchedness of being in the human body, but as it relates to family and home, and the otherworldly.

I’m curious if you see this piece of writing in the way that I’ve experienced it, which is this theme of the repulsion in one’s own genetic code, in relation to postmodern capitalist society.

As in: we’re aware that our diet and our modern way of life is cancerous and degenerative, so this repulsion with our genetic family, and eating and gathering with them, is also a repulsion to modern existence.

We feel the inherent doom as we gather in toxic spaces to ingest toxic foods in front of toxic media, staring our own faulty genetics in the face.

We’re forced to accept our inescapable genetics, even though there’s some of us that really try to extricate ourselves from that.

That sticky, repulsive warmth of the inevitable family is really, to me, the core of this book.

RR: Yeah, I mean – there’s a few things there. I’m always reading horror genre stuff, mostly early horror stuff. And those are the only movies I watch too. I just watch horror movies.

So when I’m writing, I always think that I’m writing horror, and then I’ll give it to someone and they’re like, oh, this isn’t horror.

I use the word “horror” a lot in the book, [laughs], but I don’t think saying the word “horror” makes something a horror novel no matter how often you use it.

Now, the theme of family acceptance is a big one in the book.

Everything that the book is about is kind of corny. Stuff like family acceptance isn’t generally something I would write about, and it’s also about, you know, going home and having a new relationship to the idea of home, and dealing with trauma. There’s all these things that I don’t necessarily write about and that I thought were maybe, like, too corny for me to tackle. But I guess that was the challenge: how can I make it interesting for me, how to not make it hallmark-y when I’m writing about such personal and vulnerable themes.

So maybe mixing family acceptance with a lot of body horror just made it a little bit more palpable for me and more interesting to write. And I could kind of make it more entertaining that way and not come off as cheesy.

I must admit, I’m paranoid about being cheesy.

AG: Yeah, I feel that. But it’s very not-cheesy, because often when people write about family, they feel compelled (unless they’re like, “I’m going to trash my family”) – to put it in a nice light, like “let’s see the bright side” or “I’ll be kind in case grandma reads this”. But the way it was done is incredibly unsentimental and relatable.

It brings up that thing of how there’s people like us, who were born feeling “I am of no one, and of nowhere, I am not of any people. I am of the world.” – i.e., I want to extricate myself from this whole notion, like, just this dissociation from the whole family concept, I’ve got to get out of this house. I’ve got to get out of this town.

And then there’s people that are happy to stay in their hometown, live next to their family, shack up with someone they went to high school with. Maybe even fuck people just one room over from their parents the rest of their lives, and that doesn’t make them

want to retch. They’re like, this is fine. This is life.

And that’s technically normal, right?

And then there’s us wretched anomalies, where that’s so repulsive to us.

So I like how you’re delving into the repulsion of the familial self and the nauseous reckoning it entails, but embracing it as the inevitable without being corny. Like when you sneak out after everyone passes out in a junk-food nap in front of the tv, and then

there is this passage when you return:

“My family was still asleep, a black screen on the television. I stared at them until I felt distant from them, then stared at them until I felt the same as them.

This was all I could think of: I love this city, and these people. It will, and they will, always welcome me back.”

You accept it, and it’s so beautiful. And it’s also a little queasy, which I like – it’s not saccharine. It’s like, oh god – I’m one of them. And I think most of us can relate to that.

RR: Yeah. And that’s – I mean, that’s a good read, because when I left Niagara Falls I was probably 19, and I certainly left with this idea that I was too good for Niagara Falls, and that I was way different and way better than my family.

When I returned to Niagara in the book, it was the first time I felt any “home” resonance since I moved away. I didn’t have anywhere else to go. I lost my job, and I had my studio taken away, and that’s where I was living. So my first impulse was to go back to the Falls.

At that point I still had the vestiges of this youthful feeling that I was too good to go back home, that was too good for the family, even though I felt like I was much older and wiser, I still had that feeling. It’s hard to shake it, that you’re too good to go

back.

But just being there for a while, it just kind of fell away and I was just like, okay, fine. I’m not much different than my family.

I’m no better than anyone.

AG: At the core.

RR: The judgment stuff went away. And that’s why I have all these parts about me eating bad food, because I’ve always been judgmental about them eating bad food. And eventually I was like, who cares?

It’s no difference. Who cares what they eat?

Who cares what anyone eats?

AG: Absolutely. And that aspect of it is a grand comic gesture.

You’re perceiving your family in a certain way, then escaping from their world, off on your own – a writer in a hotel room. But you’re watching TV and eating junk just like them. And that’s so many of us with our families.

We’re like, look at these people, you know, I’m gonna be better, but then as time goes on, you learn: I’m exactly that, just like, through the looking glass.

Just barely through the looking glass. Just because I read books or something, it doesn’t elevate me terribly more.

There’s a great part where the guy running [the restaurant] Happy Taste has his say. And it’s so perfect when he says that your carefully cultivated weirdness is so boring and pointless, that you’re not interesting.

In that world, you’re just – you have no cultural currency, and you shouldn’t.

You’re just fucking boring.

RR: Yeah, because there’s a limit to how much you can know anyone, or be like anyone else. There is a limit to how much you can connect with pretty much anyone, even someone that you’ve lived with your entire life.

So I wanted to make sure that this was one of the final notes in the book, that there’s always going to be this edge of mystery to everyone, to each other. That’s not a bad thing either.

Try to enjoy the human connections, and embrace human difference.

AG: Yeah. It’s like that relief you get when you’re at a bar or somewhere and you try to have a conversation with someone and then you both kind of realize – oh, this isn’t going to happen. Like we don’t – we have no connection.

It’s fine.

It’s a relief, really.

RR: Sometimes I’m actually envious of my family now because they’re all so content. And they’re happy for the same reasons that I rejected or avoided. Like, they all live either with each other – so many of them just live in the same fucking house, or they live just blocks away. Everyone’s just really close to each other.

And I was like, oh, I do not want to be that. I want to get out of here.

But then when I go back, I mean, they’re so, like, close knit, and if anything happens, they could support each other. There’s so much convenience in their lives. And I know it’s kind of a nihilistic thing to say, but it just doesn’t matter.

It just doesn’t matter if I left or if I didn’t leave, you know – there have certainly been some benefits of me leaving, but if I didn’t, I would have what they have: a support system I lack, a contentment I lack.

So it all comes out in the wash, I guess, is what I’m trying to say.

AG: Intentional or not, there are aspects to the book that read like an addict novel. You’re having this seedy compulsion towards junk food – there’s a lot of mouth-watering passages that are kind of perverse. And your fantasizing or excitement about junk food is akin to junkie romances.

You’re traversing these low life experiences of like – okay, I’m getting cheaper and cheaper motels, things are getting darker and more surreal. But the addiction is just this trash-ass food, and there’s this back and forth between being repulsed by it, but also revelling in it and feeling taken care of by it, like heroin is often described.

And then that mirroring with the family – it’s repulsive, but it’s comforting, and it’s also making you sick.

So yeah, it’s comically a bit of a drug diary, but it’s the junkie relationship to our American junk food.

RR: And I’ve never thought of that, but, you know, during that period – I guess I won’t answer any of the mysteries of what in the book was true or not. But I mean, it was all true, even if some of the stuff didn’t actually happen.

I wonder if I should elaborate on that?

No, I’ll just leave that as a mysterious, enigmatic quote…

So a lot of those experiences that happened in the book may not have happened in the right chronological order.

So during the time in which the book takes place, I didn’t do any drugs, I didn’t know where to get them, and I didn’t drink because I don’t like wasting my money on booze if I don’t have any money. So although the junk food plays a big part because of the connection with my family, maybe I also used it as a way of like, since I knew I had to write a transgressive book that didn’t have booze or drugs involved, I needed to make it transgressive and gritty, as in an Arby’s.

AG: Which it is! And it’s unique in that way.

And I like it because I hate the whole dusty thing of like, oh, I’m on heroin, I’m so edgy. It’s like, big deal. You fucking do drugs.

I find it much more horrifying if you’re eating casino food and Arby’s. Now that’s a pretty fucked up thing to do to your body, that’s edgy as hell [laughs].

RR: Very true, and you know, Chinese takeout and Arby’s and stuff – that tastes better than old dried shrooms.

The taste of a Wendy’s frosty over the taste of a Pabst Blue Ribbon?

Come on, it’s no contest.

AG: You have a “Goblin” character that recurs in the book.

I read it as the embodiment of the repulsive genetic self: it’s in the family house. It’s with all your shit in the basement. And it’s more body-horror; I mean, just a goblin in general represents repulsion and bodily disgust.

And your goblin is a bit of a classic goblin. It’s pissing, it’s oozing, it’s doing gross things with its body for no reason at all. And it’s reflecting you back to yourself.

And yet, you’re compelled to follow it or engage with it.

RR: [Laughing] I’m laughing because every time I talk to someone about the book, I feel like I haven’t read it. It’s like someone is asking me these questions and you have like, my answer to the question – but they’re just guesses.

Some of the stuff in the book, I had no idea what I was doing.

With Ric noting: “Here is a trick where I would swallow a $20 bill, then drink gummy bears blended with egg nog until I throw up the $20 bill and a lucky audience member would win it.”

[Photo by Chris Anderson]

AG: [Laughing] Yeah, I feel like art is like that.

RR: When I started writing the Goblin thing, it was in a draft and I figured, okay, let’s just get this down and you’ll rewrite it because you’re not going to use the word goblin. Stupid word. And then as I kept reworking drafts, I was just like, no, actually, this part should be stupid. These fantasy parts should look like they were written by your 14 year old self. Those goblin fantasy parts should be a little bit rougher around the edges, and maybe sound like a more juvenile Ric Royer wrote them.

Maybe it’ll work, and maybe it won’t.

AG: It’s like it is your childhood or something, or a pubescent self. It lingers around your ickier feelings or memories, or your old belongings, your comic books. In tandem with the Goblin is all the hyper-sexual parts of the book.

Like we talked about earlier, the book is about family and yet filled with grotesquery and hyper-sexual imagery. It touches that ickiness of being a sexual being around your family. That being-horny-in-your-hometown thing – again, the two types of people where, like, some people are only horny in their hometown, they’re horny for their hometown and for people in their hometown.

RR: I may not have given my own book a real good deep reading like you have and everyone else has. But I do remember one line, and that is when I’m wondering how to hook up in a small town, and I have the idea that maybe I should go around to look for love in some bars.

But I can’t because I’m worried that my dad would be there.

AG: Yeah, exactly.

RR: It’s such a chilling thought.

AG: It’s such a violent divide, I mean, I grew up with people that have no problem hooking up with someone they meet in a bar while sitting next to their dad.

Once again, for some it’s just small town life or tribal life and how it’s always been, and then for others, it’s a nightmare. So yeah, I appreciate the weaving in of the grotesque and the perverse.

Also, knowing about your whole job writing about the giant penises, I was happy to see the cross-pollination.

RR: That’ll be a good line to keep in the interview: “Your job with the whole big penises thing.”

AG: I’ll just let it be that. “Knowing about your whole Big Penis Job, and the fact that you just weave that into the narrative is great.”

RR: I mean, that’s just – that was just a stroke of luck.

I felt weird just saying the word stroke in this context, but a giant stroke of luck was that I’ve had all this practice writing about giant penises because of my job.

I was planning on putting the images of large penises in the book because of this drawing – in the very beginning of the book, I talk about this drawing that used to be on my fridge after my mom and my dad divorced.

I was seven or eight. My mom got a little loose, and she had this drawing on the fridge for a long time, an illustration of a Native American using his giant like, like, three foot dick as the bow of a bow and arrow. So it would like, come up and arc around and, you know, there was an arrow being slung between it, and I was pretty young to have that just sitting on the fridge.

And so all of these things sort of orbiting my brain around trying to understand sex and sexuality, but then it being very like, in my

face. And that was like one of the very first early memories of, um, you know, being a kid working out what sex is because, yeah, just about everyone has some sort of funny story about, like, what they thought sex was when they were a kid.

So I thought like, damn, when I get older dicks are going to be like, almost as big as my whole body.

AG: Yeah, just like, ‘That’s going to be me.’

I found an 80s Penthouse magazine when I was a little girl and I was like, yes, that’ll be me when I grow up. Like these giant, like, 80s watermelon tits. I was like, “That’s what I’m going to look like”, or, “that’s sex”. A hairless slit and watermelon tits – ok, that’s a woman. Got it. And it’s so hyper-stylized.

But you’re like, “Okay, I guess that’s the thing,” because you don’t know.

RR: Yeah, I guess what I’m saying is I didn’t add all the stuff about big dicks because I have a job in which I write about big dicks a lot. That was just like pure luck that I had all this practice writing about this stuff, because I wanted to get weird early sex fantasies into the book.

Maybe too many big dicks than it needed to.

That was actually [my partner] Miriam’s criticism: there were too many big dicks.

AG: I think the pull-quote for this article is going to be “it probably had more big dicks than it needed”.

So, a character in one of the ‘big dick’ scenes is this person that lives full-time in the seedy side of Niagara, and you develop a bit of a fascination with her as you slip further into the underbelly of the town. And this slip across the divide touches on these attempts to believe ‘I’m better than my family’ or perhaps ‘I’m not trash’, and yet, who says you are any better?

Like [my partner] and I laugh about how we occasionally find ourselves walking along a highway looking eccentric and realizing, ‘We are the trashy people walking along the side of the highway.’

Like, oh, you think you’re above that? But right now, we are the walking trash, and everyone driving by is thinking, why are they walking there?

If you’re in most parts of America, if you’re walking at all, you’re seen as trash. And that’s why I loved this constant theme of you feeling so wretched, and that you don’t belong anywhere, and you are embodying what America sees as wretched: the godforsaken figure traversing an empty parking lot, or walking along the side of a road.

It’s this dystopian capitalist landscape where if you’re walking, you’re a failure.

RR: Or you’re “The Walker.”

Like when I was spending a lot of time at that house, which is where my mom, my grandma, where everyone lives. Every time I would walk down that block, like to go to Dairy Queen or the mall or something, and I had to pass all the other houses, I just kept thinking that everyone was looking at me being like, oh, there’s The Walker.

AG: I’m sure they were.

RR: Because no one else walks. Nobody walks in Niagara Falls.

So just like, even if they weren’t judging me as trashy, they were definitely singling me out as The Walker. The Niagara Falls walking guy.

AG: It’s just such a post-capitalist dystopia because I mean – this how we get around, guys. This is how this works.

Yet within capitalism, it’s like, oh, that’s an oddball failure who can’t afford a car. It’s shameful.

My parents always hung out at their friend’s restaurant at the end of our street, and it was about one short block from our house. They refused to walk there, because they thought it was embarrassing. They’d get in the car, pull out, and drive the one block down and park, to avoid the shame of walking.

I think it’s specific to working class people, middle class people – like rich people would walk, right? But working people wouldn’t dare be seen walking.

“I’d look like a vagrant!”

RR: Yeah, I’m not sure if if I make it clear in the book that The Wagon Wheel, the bar that my dad goes to, is like four houses down from where he lives, and he still drives.

AG: Oh my god [laughing], it’s the same thing.

Yeah.

RR: I always hoped that he would get pulled over, like just pulling out of the parking lot and the cops would be like, what are you doing? Your address is like, right there.

Leave your car here in the parking lot and just walk home.

AG: Oh, man. Even though probably in many ways our upbringings are nothing alike, I felt a lot of analogues in your book to my life. Like the receiving the big bag of frozen sausages from your father right when he picks you up. And being like, what the fuck?

Of all the things to hand me right now when I just arrive.

And then they’re melting in your bag. And it’s just like, goddamnit.

Then you end up feeling forced to throw them in the trash.

Later, you’re sad about it, because it was a nice gesture.

RR: It makes me sad. Because in some families, definitely mine, the more older and distant you get from your family, or at least how different your lives become from your family. There’s only a few ways that you can connect.

I keep saying ‘you’, but I’m assuming this happens to other people. But for me, my dad and I, we have the Buffalo Bills, the Buffalo Sabres, and dad food, like smokers and grills and sausage and that’s that’s all we talk about.

Like, we don’t talk about jobs. We don’t talk about health. We don’t talk about politics, current events. It’s the only like three things that we really connect on.

So that’s why that moment made me sad to have to throw away because I realized, okay, that’s a big deal. That’s one of the connective things with me and my dad. And he probably was like, “Ric’s coming into town. Better give him those sausages he likes.” I sometimes forget how meaningful these limited connection points are.

And that was one of those moments, I actually felt bad having to throw the sausage away.

Even when he gives me food now that’s nasty, I’ll just try and find something to do with it, like I still have. He gave me this like, um, weird fucking venison thing. It’s a long piece of venison. I don’t even know what part of the deer it comes off of. But he gave me this thing. It’s frozen. It’s still in my freezer. I’m probably never going to eat it, it’s just going to disintegrate into ice.

But I just can’t throw it away. And I’ve had it there going on two years.

AG: Well, it’s a gesture of love.

I mean, you know that it’s a gesture of love because he also knows innately that that’s a way to connect with his son and show him he loves him, is to give him food, to give him this food he makes.

RR: Without it, it would just be complete silence.

You know there’s nothing to talk about.

AG: I was recently remembering throwing away these lovingly packed lunchbags my parents would give me from their deli they ran, every day. And lot of days I walked into school and immediately chucked it in the trash.

There were probably many reasons I did that, but usually it was simple – I had no time to eat, I didn’t want to carry it, I wasn’t hungry.

Looking back, it makes me want to cry. The fact that they took the time at their hectic business and made it with love, packed it all nice, and pictured me enjoying it, and I just walk into school and dump it in the trash can.

In your book, when you finally are like this fucking bag of sausages and you unload it, and then you’re so sad about it later, it feels like a giant symbol for parental love. Because you’re like, I don’t know what to do with this shit. I’m trying to live my life and just – stop loving me, like, leave me alone.

But one day they’ll die. And it’s like, damn it, I want those sausages back.

It’s just so palpable.

RR: Yeah, they’re a hassle too.

AG: As your friend, I’m aware of how you were unjustly pushed out of town when you lived in Baltimore. You had essentially put your life’s work into creating vibrant art spaces, the culmination of being a writer, a director, a theatre person, a community uplifter.

You helped rebuild a community, and created these arts hubs and fostered so much great work in Baltimore, and then had it quite unfairly ripped out from under you. You were left with basically nothing, and the book begins with this reckoning.

The reckoning with the true self, because your self was the life that you had built in Baltimore.

I don’t think a lot of people reading the book will know the depth to what you had been through…

So underneath, the book seems to ask – what is a person when their life’s work, their home, and their chosen family is taken away from them?

This is where the poignancy in the plot lies, because it’s not like you’re choosing to go back to your family. It’s just the sinew and bone left to yourself.

RR: That all happened in 2018, when there was this mass spectacle of people being tossed into oblivion. And if your number was called there was nothing you could do about it.

During that wave of public shaming, people focused on the actual process while it’s happening, like a televised trial, but then

lose interest once it’s over. Then you are gone.

People don’t know where you are. People don’t know what you’re doing. You’re kind of alone, and all of your supporters have to go back to their own lives, because there’s only so much that people can, you know, devote of their own lives to helping you get

back on your feet.

So I thought that “after the crisis” phase was a really interesting period to write about, because you don’t often hear about that period – what do people do after. I thought it was more rich to talk about, the time when you’re supposed to be dead.

I kept hearing that phrase over and over again. “Oh, man, your life is over” or “your life’s ruined,” “They ruined your life,” or whatever. Yeah. And what happens when you keep hearing those phrases repeated, but then you’re still alive.

It’s never mentioned in the book, the shit that went down prior to me arriving in Niagara Falls. It’s left mysterious – there was some vague calamitous event. I let it be a mystery because, for one, I like mystery, leaving things for the reader to figure out. But also, I didn’t want it to be that kind of book. I didn’t want it to be about cancel culture or anything like that, just my general ghostliness of being.

I don’t mind talking about it.

Such a weird time.

Now I’m able to just look at it from more of a perspective of fascination as opposed to just being completely destroyed by it. I could kind of look at it from somewhat of a distance and think, isn’t that strange? [laughs] Yeah, sure, it sucks, but isn’t it strange, too?

And it’s really hard to write about it deftly. So I felt like the best way to write about it was to just slather it with the metaphor and mystery.

AG: I’m glad you made that choice.

I prefer abstraction in art, art being art, an intangible expression of the human experience and not like some kind of literal treatise. I used to have a friend that would say, “Any art that’s made for a cause sucks.” And I don’t disagree – it’s a blanket statement, but his point would be that the minute you’re making the art for a separate purpose than the pure expression of the thing, then that other purpose becomes the focus, and the quality suffers.

It stops being a pure, transformative expression of the human experience that isn’t anything else.

Art shouldn’t be a literal anything – that’s what makes it art. I mean, I don’t want you to sit and write about literally everything that happened for many reasons. I think I understand you more through something like this.

RR: Yeah, I’m just thinking about how the more an artist thinks of themselves as a politically radical person, the more it tends to mean that the work is going to be completely not radical at all.

AG: After I first saw you doing The Coincidental Hour, I worked with you as a playwright and a director, and I’m curious about your prose writing informing your theatre writing or vice versa – your path as a theatre director, and your general artist’s path.

How did you arrive to where you are now creatively?

RR: Well, I was always more of a theatre person until about my junior year of undergrad. Because I started to figure out how amazing the University of Buffalo poetics program was at that time.

AG: Oh, yeah!

RR: Yeah, Robert Creeley was there, and Charles Bernstein and Susan Howe, Samuel Delaney was there. And Michael Basinski, who is one of my favorite poets.

So I got involved in the poetics program, I’ve always been like half writer, half performer ever since. But for a long time I had this, like, conceptual thing where I wanted performance to be ephemeral only, and I wouldn’t record anything…

AG: Oh, man. I relate to this.

RR: I didn’t want to write anything down or have anything published.

AG: Were you mainly performing?

You weren’t writing plays yet, you were studying acting?

RR: Yeah. I don’t think I did my first, like even chapbook until the end of my senior year of undergrad.

AG: So more theatre performance, and then into poetry.

RR: Yeah. Or just weird – like a weird structural, experimental writing stuff.

I figured out after a few years of not recording or writing anything, or documenting in any way, that that could be a little bit detrimental to one’s career. And especially as I got older, like starting my 30s or mid to late 30s and especially now the older I get, the more I want to write things down and record things because you’re just getting older and you’re starting to think, you know, you have less time.

There’s a quote that I always think of from Kathy Acker. I think it’s in the Empire of the Senseless. I’ll probably mangle it. I’ll probably have to look for it again. But it’s something like, “It’s against death that I record these memories.”

Just trying to expand the idea of what your life is.

So it’s like, okay, my life is getting shorter, so maybe I can create some longer reverberations after I’m gone, yeah?

So I think that’s why I’m writing more now: against death.

AG: But you had published some plays, during the time you were mainly acting; right?

RR: I had a couple of books published. That was 2008, 2009. I kind of decided I was going to be more of a writer.

But because I’ve been performing so much and I didn’t get that immediate gratification of everyone clapping for for you after the books came out, I was like, fuck that. It’s really depressing. I worked on these books for so long, and then I release them and nothing happens!

But I don’t know, now it seems different for this book. I don’t need instant gratification anymore perhaps. So maybe I’ll stick with this writing thing.

AG: Right.

So before the the big “cancel”, you were mainly directing theatre, and you had these giant art spaces that you were building and running.

RR: Yeah, I was writing and performing in theatre, and running show spaces.

I was planning on quitting running the spaces, because it was all getting to be a little bit thankless. Especially when you get kicked out of town for it.

AG: Do you imagine yourself going back into theatre a little bit more, or are you neutral about it?

RR: I feel neutral about it right now. It’s just harder logistically.

Writing Niagara Falls, NY it was fun. It went really fast, and it was really enjoyable. I want to hurry up and write the next thing really quick, while I’ve still got that muscle memory in my head – like how it worked to make it fun. Because it’s so much easier to just go in your studio and write.

Especially if you have a fun process. I do a lot of collaging and cutting up words and recording, like secretly recording conversations on the street.

So, you know, if I’m in my little lab writing on my own and I crank out a few pages, it’s so much easier than figuring out

everyone’s schedule to see if they can get a rehearsal in.

AG: Oh god.

RR: And trying to get all the tech stuff straightened out and, like, bringing a bunch of props and costumes.

The idea that I just sat in my room and did this, it really makes me put like a little bit of pause on doing theatre.

AG: Yeah. Yes [laughs], and I think that’s a very intelligent conclusion to come to.

That’s a little too sane!

Oh shit. I guess I should start writing something.

RR: Yeah, Imagine that.

You don’t have to even go anywhere.

You’re just in your house.

Links

- Link to Buy Niagara Falls, NY – via Pig Roast Publishing

- Ric Royer – Website

- Ric Royer – Blog

- Ric Royer – Blog 2

- Ric Royer – Instagram

- Ric Royer – Facebook

- Ric Royer – twitter

- Ric Royer – YouTube

- Model City Books – Website & Online Store

- Model City Books – Instagram

All images supplied by Ric.