- Title: ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’

- Editor: Justin Isis

- Authors: Brendan Connell, Golnoosh Nour, Arturo Calderon, Gaurav Monga, Audrey Szasz, Colby Smith, LC von Hessen, James Champagne, Kristine Ong Muslim, Damian Murphy, and Justin Isis

- Cover Artist: Gea*

- Publisher: Zagava Books

- Year of Release: 2023

- ISBN: 978-3-949341-32-8

- Page Count: 272

- RRP: 22Euro – Paperback Edition

Regular readers of The Aither should be at least partially aware of the Neo-Decadents, a loose confederation of writers, poets, and artists with an axe to grind against the imagination-starved tedium of much of what passes for “contemporary culture.” Over the past half-decade or so this small but growing cadre has been both spitting both venomous bile and seeds of renewal, producing in the process a steady stream of fiction, manifestos, and poetry.

‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ (published by Zagava Books, 2023) is the fourth anthology collection from the movement – following the polemics of ‘Neo-Decadence: 12 Manifestos‘ (Snuggly Books, 2021), and two prior collections of fiction, ‘Drowning in Beauty‘ (Snuggly Books, 2018) and ‘The Neo-Decadent Cookbook‘ (Eibonvale Press, 2020) – and provides fortunate readers with eleven shots of truly 21st century fiction.

For a few years now the Tokyo-based writer and occultist Justin Isis has been promoting and theorising Neo-Decadence with zeal, and as editor of Neo-Decadence Evangelion he has provided us with the strongest example yet of this burgeoning movement’s cosmopolitan vision. The authors here are scattered across Europe, Asia, and the Americas; their stories taking place in Tehran, Lima, Okayama, and beyond. This near-global span is reflected in the range of styles here, with the near-dozen stories varying from cruel fable to blissed-out erotica, from scalpel-sharp satire to exhilarating fabulism.

There’s a lot to cover here, so without delay, insufflate a dose of your favourite psychedelic stimulant (if you indulge) and prepare to jump right in…

Kicking things off in delightfully dark fashion is Brendan Connell’s “The Slug,” a conte-cruel that reads almost as an epigraph for the rest of the book, acting as a literary palate cleanser that readies the reader for the peculiar indulgences ahead.

In a series of terse barbs of prose we join one Dino as he dives willingly from his rung near the top of the socio-economic ladder into a void of financial and moral poverty, delighting in his own fall. The descent into squalor and slime is a perennial decadent theme, and in some ways “The Slug” echoes back to Paul Leppin’s distillation of literary misery Blaugast, but instead of dissolving into masochistic sorrow Dino wades into the abyssal darkness willingly, brought to glee by his own disgust, self-observed and otherwise.

Bleak stuff for sure, but not without poisoned barbs of vantablack humour, like when Dino’s bizarre erotic tastes lead to his rejection by even the basest of libertines, and he is forced to find alternative means of satisfaction:

“Dino, as passionate as any chamois or barnyard animal, was constrained to seek pleasure from knobby trees, sidewalk cracks and other inanimate objects of symbolic significance.”

Erotic mores of a more conventional sort are explored in Golnoosh Nour’s “Sadprince.”

Prospective readers are advised before reading to crack a window open or turn up the air conditioning, as the hot sting of erotism practically burns off the page. In this tale of desire rewarded Tehran is our locale, a Tehran “throbbing like an open wound,” where the titular sad prince Ali holds court. Our narrator is enamoured by Ali, at first by his Dennis Cooper-esque sadomasochistic blog posts and later by his magnetic persona:

“He is an idol. A strange angel. I burnt all my other books after I discovered his blog. I don’t want to consume any other form of art apart from his insanely graphic descriptions of boys bruising each other.

Because when I read him, I am the one being consumed. And I enjoy this consumption, for I am both the bruised boy and the bruiser.”

Ali has recently turned 40 and fears his erotic relevance is waning, much to the narrator’s distress. She procures her friend Nima for Ali’s satisfaction, and by extension her own vicarious thrill, her fixation on Ali having shifted from a thirst for attention to one of recondite desire.

“Sadprince” is a deft character study of obsession described in vivacious prose.

Nour has previously explored Tehran’s queer underground in the short fiction collection The Ministry of Guidance, but in “Sadprince” the desire and lust is raised to suitably decadent levels. Iran’s queer culture can be presented by Western media through a patronising lens, and it is refreshing and necessary to hear from a genuine voice, defiant and proud, lurching towards life and pleasure:

“I feel I am dreaming and one of my dreams has come true. Unlike most of my acquaintances and relatives, I don’t have to leave my country for my dreams to come true.

My dreams are beyond the superficial notions of Western success. My dream is right here.”

Neo-Decadence Evangelion’s editor and general cultural gadfly Justin Isis is up next with the enigmatic “A Tree Rotting from the Top Down,” where after a humiliating event in his childhood, Kousuke dedicates the totality of his life towards vengeance. His target is Kawamoto, a doctor some twenty years his senior.

At Kawamoto’s wedding years ago, the child Kousuke had wandered away from the adults at the reception. While sitting on the street outside his boredom was erased by the sight of an enormous beetle, a moment of extraordinary visionary significance:

“The smooth divisions of its shell seemed deliberately sculpted, not anything nature could have produced. The line where its halves came together seemed as if it could open into something other than a wing case; he imagined it splitting apart to reveal a perfectly blue eye, or a tiny glass window to another world.”

Kousuke rushed inside, desperate to share with someone this glimpse of overwhelming Beauty. His breathless babblings to the groom’s table provoked only ire from Kawamoto, who with a few sharp words scoured Kousuke of all wonder, replacing it with embarrassment and burning resentment.

It is from this moment on that Kousuke makes Kawamoto’s total social immolation his life’s work.

Fuelled by the desire for revenge he thrives academically, breezing through medical school and quickly becoming a doctor. He consciously exceeds every aspect of Kawamoto’s academic and clinical performance; upon discovering that Kawamoto is a general practitioner Kousuke one-ups him by becoming a renowned specialist in ophthalmology. The years pass like weeks and soon he is on track to marry Rika, her own name echoing that of Kawamoto’s wife, Rina. A wedding is planned, the clueless Kawamoto invited as guest of honour, and Kousuke sets a bizarre plan in motion.

Meanwhile, Kousuke’s sister Aki lacks his relentless drive. Her life has been harrowed by the miseries of her mother, a cold and distant woman, one who is:

“beset by the tyranny of internal organs. […] A great sickness had settled over her while carrying Kousuke; Aki had been even worse; she had not so much birthed as dislodged them.”

Aki leaves high school and works at a hostess bar, before being bullied and then aged-out of her job. She becomes a professional gambler, and while Kousuke’s blinding hatred benefits from having a defined target, her own negativity turns inwards. She drifts through life, finding temporary solace in consumerism and addiction, only to end up ensnared in their traps.

While both siblings are emotionally stunted and occasionally pathetic, Aki’s story lacks the strange humour of Kousuke’s, and has a darkness to it that at times borders on cruel. Is this glib nihilism, or an honest attempt at illuminating the motives and actions that emanate from a wounded psyche? I think it’s fair to say that it’s more than a pinch of both.

There’s a peculiar occult undercurrent to this story, the first hint of a theme that reveals itself in different guises throughout Neo-Decadence Evangelion. Kousuke’s quest for vengeance is obsessive and total, a kind of perverted Great Work; the enormous beetle of his childhood is like a guardian spirit, its appearance changing the trajectory of his life forever. The story itself is rife with subtle mirrorings; and there are brief but tantalisingly hints of a kind on arcane geometry influencing Kousuke’s life:

“At the moment of his encounter with Kawamoto, reality had assumed for him the shape and consistency of a metal cage, a confining structure of fixed and distinct components. The world had been coated in lead, but now it was dissolving to reveal an architecture of frozen light, each passing day stripping a little more of the confining weight away.”

Isis writes with diamond precision, each sentence sharp and glowing but never excessive. Both Kousuke and Aki’s psychic states are examined with an unflinching surgical eye. Their two malformed personalities, tragic but also repellant, are portrayed without gloss, even to the point of discomfort. To some this may read nihilistic, an assessment that holds some water.

Whatever the existential outlook of the piece, “A Tree Rotting From the Top Down” is a highlight of Neo-Decadence Evangelion.

Crossing continents from Asia to South America brings us to the collection’s finest piece, Arturo Calderon‘s “Yawar Jaguar.” This adrenalizing story is an up-to-the-millisecond snapshot of our aching world as it stands in the third decade of the 21st century, told in breathless, incandescent prose that illumines many of the secret and arcane details hiding in plain sight of our troubled age.

A chance meeting with a taxidermied jaguar has young Urpi ensorcelled.

In the early hours she watches YouTube videos of big cat dental surgery, although these rough analogues can only imitate the aesthetic high that seeing the preserved panther provided. Obsession, that familiar guiding spirit of decadent fiction old and new, burns in Urpi with an intensity bordering on the spiritual:

“Even months after that landmark moment in her early years of university life, the view would spook her in dreams; not in the same way a nightmare would wake you up covered in sweat and saliva because you feel terrified but, in a way, closer to the ecstasy some saints have reported feeling during a religious experience; it was an aesthetic hunger for the stuffed Jaguar.”

Urpi lives in Lima where she splits her time between streaming and studying. The dull hedonism of young adulthood is adequate, if not entirely satisfying. Like many others raised by the internet, she has an omnivorous hunger for new information, new sensations. She thirsts for the new, like any good Neo-Decadent, and the tail-chasing concerns of academia just aren’t providing cultural sustenance in this new century:

“Against all odds, Postmodernism didn’t scare her. She didn’t need to listen to the same bearded old men going on the same overdiscussed topics forever, like an endless loop on a Spotify playlist that some insomniac forgot to pause before that highly anticipated date with Morpheus.

What she wanted was to do something, a gesture as small as frowning when faced with an uncomfortable question about her online shopping habits during an economic crisis but as powerful as the bombs that ended an era and gave way to the brain rewiring that Western and Eastern Civilizations are still processing. Baudrillard was no Fat Man; Derrida, no Little Boy.”

Urpi’s classmate Jolyne also craves the infinity of novelty. Transfixed by Urpi after spotting her by chance in a lecture, this fixation quickly turns into an obsession, her own Jaguar to chase. She must connect with Urpi, and sets in motion a collision course that can only end in a great poetic conflagration.

This second half of the story rolls with kinetic momentum more commonly seen in comics than prose; in fact while reading I found myself drawing parallels with the underrated ‘Roly Poly‘ by Daniel Semanas. That was a truly invigorating comic, and the energy coming off of the page in “Yawar Jaguar” is similarly palpable, with Semanas’ neon dreams swapped for Calderon’s breathless and electric prose:

“Some silver men got into nearby taxis and the street lights were violet and blue. The eyes of a Justice sculpture were melting into a crimson waterfall and the dogs kept the whole city awake with a little help from pornography and fast food.

Urpi was as pale as snow, her cinnamon skin having morphed without warning into marble; Jolyne, who was the mysterious figure, had turned into an ebony carving and the sun on the other side of the planet was trying to stream its sunbeams surreptitiously into her body, using the moon as a big reflector.

Lima citizens were no strangers to street fights between different gangs, football hooligans and their own idiotic politicians. Their knowledge had a fatal flaw, though: they were illiterate in signs and symbols. The semiotics of a street ritual were light years beyond their comprehension. One couldn’t help but hope that psychedelics and fashion would soon crash through their skulls and propel them into the XXII century, where they rightfully belonged.”

As far as I can tell “Yawar Jaguar” is Calderon’s first published piece in English, making it one hell of a debut. Scraps of influence from Brendan Connell’s novels – particularly the encyclopaedic-in-miniature detailing of his Clark and Metrophilias – and Justin Isis’ fiction are evident, but Calderon has synthesised these influences with the contents of his own aesthetic Wunderkammer into a confident, distinct, and new voice. Parts of “Yawar Jaguar” read like Jet Set Radio scripted by Jules Laforgue, others like Hirohiko Araki illustrating the dreams of Mina Loy; and any fiction that evokes such delighting and arcane comparisons is worthy of the attention of any and all enthusiasts of inventive and vital prose.

Changing gears from the hypercoloured poetics and moral duplicities of the previous stories is Gaurav Monga’s “The Costume.” The violence and sex of previous stories is also absent, but obsession still burns, albeit with a gentler flame.

The subject here is Feroz, more specifically Feroz’s lifelong dedication to the Pathani suit. Once dressed in them as a child, Feroz rediscovers their comforts in his early 20s and embraces their soft comfort as the sole outfit for the rest of his life. A born wanderer, the Pathani suit for Feroz offers stability in an unpredictable world:

“He asked himself, when he bought his first batch of Pathani suits, that what if he continued this pattern for the rest of his life? Would not all this repetition, like the learning of 88 grammar rules by constant drilling, offer grounding to his otherwise nomadic existence?”

“The Costume” itself offers a reprieve from the more chaotic and explosive pieces of Neo-Decadence Evangelion. Toeing the line between story and prose poem, each paragraph is appropriately tailored to precision, each sentence a vital thread of the greater whole. There’s barely a wasted word here, yet “The Costume” doesn’t read like an exercise in cold minimalism or reduction. Instead, “The Costume” is haloed with a soft glow of subtle humour, and shaded with quiet melancholy. Despite being set largely on the Indian subcontinent, the prose at times reminds me of the the Central European eccentrics of the early 20th century, like of Robert Walser or Bruno Schulz:

“He even emotionally blackmailed his mother to ensure that no concession was made in spending money on his clothes, by saying that these Pathani suits were gifts for all the birthdays she had missed while he was away at boarding school. He had, after all, learnt the habit of excess – in regards not only to clothing but in terms of keeping the house stocked with all kinds of furniture, carpets, accessories and even food – from her.

In his cupboard he had kept 93 rolls of fabric – he feared the cloth might someday grow extinct- for Pathani suits he planned to have tailored in the future.”

Monga’s story reads as the final piece of the first act of the anthology, like an aesthetic palette cleanser before the next course. Intentional or not, there is a detectable change in tone with the next few stories – nothing here by any stretch is bad per se, but the next handful of pieces don’t quite hit the same inventive highs as their predecessors.

First up is Audrey Szasz with’ “Fred is Dead,” a fractured narrative with an abyss-black sense of humour, as hinted in the snotty irreverence of the story’s subtitle: “Concerning My Unpaid Internship at the Rosemary West Centre for Spiritual Development.”

For the luckily unaware, Rosemary West and her husband Fred were a particularly vile pair of lust-murderers in South-West England from the late 1960s to the 1980s, and one of the prominent threads of story here involves our narrator Dorka as she assists Rosemary West with a kind of agony aunt column, reading emails to her and typing up answers.

The exchanges between the two provide much of the deadly and deadpan humour of the story:

“That’s the secret to a lasting relationship,” Aunt Rose went on.

“Sharing, compromising, spicing things up, having a little bit of fun on the side.”

“Wait a minute, didn’t you, like, murder your own daughter?”

“Exactly. Fred cut her legs and arms off, put her in the dustbin, put the lid on and put her in the cupboard under the basement stairs. Then he buried her in the garden.”

The feeling here is that this is much more of an Audrey Szasz text than it is a Neo-Decadent one. I’ve read a bit from Szasz’ before – her acridly funny chapbook Invisibility: A Manifesto I especially enjoyed – and “Fred is Dead” hits many of the beats that appear elsewhere in her oeuvre. There’s a push-and-pull between psychosexual trauma and torture, bleak black humour, and hallucinatory lyricism that may read as typical to this anthology, but there’s just something a bit off in terms of how the story sits with the wider collection.

I did read another review of Neo-Decadence Evangelion in which the writer considered this to be the highlight of the whole book, so your mileage may very well vary on this. Perhaps evident of my own personal tastes in prose, I found the best parts of “Fred is Dead” to be the moments of feverish and crystalline imagery:

“I stare out of the window. Comets with herpetoid tails appear upon the horizon. They slither across the onyx porcelain of the night sky. I have always enjoyed looking at the moon through a telescope or a pair of expensive binoculars.

I experience gazing at the lunar surface almost as a hyperreal event, if that makes any sense at all. It’s like I’m viewing an apparition. The craters, the textures, the markings, the shape of it. Its very roundness, its curvature, like a giant beachball made of silica and basalt. Like the Sat.1 logo looming in the heavens like an insult so accurate and biting that it never truly fades. The southern lunar highlands. Tycho, Pictet and Sassarides.

Glorious craters attesting to heavenly impacts! Stoic moon in your supreme indifference!“

Colby Smith’s “Hellenic Dropout” follows, continuing with the dark tone. Detailing the short and brutal life of the Romanian hellrake Alin, this story is imbued with bitter nihilism that is tempered with shards of arresting imagery. The sickly excess of this nihilism unfortunately overwhelms the story, and robs it of a satisfying climax.

Our hero, or rather anti-hero, stalks Bucharest’s shadowy underbelly for drugs, sex, and violence. He courts notoriety and provokes his neighbours, brandishing his helltorso: a full-abdomen tattoo of the right panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (you know the one, with the shitting bird demons and mutant treepeople.) He dabbles in steroids and engages with various lowlifes and miserabilists, cuckolds and fights both friends and enemies, and partakes in other escapades generally understood to be shitty behaviour.

His urges towards self-destruction enter overdrive and it isn’t long before he has sucked others into his whirlpool of misery and death.

This surfeit of darkness ends up working against “Hellenic Dropout.” It’s just that it comes across as too much, and this darkness lacks the psychological insight of Justin Isis, or the black humour of Audrey Szasz. Where Smith fares best is with his charged descriptions and eclectic similes – a young drug dealer enters a scene “looking like a quetzal bird,” a boy’s speech is “slurred like a cauldron of concrete.” When Alin begins using steroids he becomes “an emperor in plainclothes. The muscles […] akin to the colossal antlers of an elk, or the thousand eyes on a peacock’s tail.” The peculiar poetry of these moments would do very well in a more dynamic piece of writing, and great things have been said elsewhere about Smith’s recent collaborative poem-comic with Josh Bayer, ‘Fish Turns Colors Then Break In My Hands.‘

Brendan Connell’s “The Slug” tells a similar tale to this one, but by being lean and steely it succeeds where this one fails. Likewise, the Milanese setting there wasn’t essential to the telling of that story but it was gently evident, this subtlety working in the story’s favour; whereas here Bucharest comes off as inessential to the story but is over-presented in the telling, coming off unconvincing. Perhaps it’s unfair to compare Smith, who is still a young writer who is developing and refining his style, with Connell, who has been publishing for 20 years.

Having “Hellenic Dropout” placed directly after another story of evil and misery probably works against it, too. There are jewels in Smith’s words, they just need some contrast and refining in order to shine.

The final third of this collection more explicitly embraces the arcane and occult aspects that other stories in the volume previously hinted at.

In just a dozen pages Kristine Ong-Muslim’s “The Black Zodiac” is a potent dose of bleak psychedelia, taking the form of a handful of mythopoeic vignettes that combine folklore from the indigenous peoples of the Philippines with the most alien products of science-fiction’s New Wave. This haunting cycle describes strange archetypes like the Man in the Loop, the Fire-haired Messenger, and the Black Zodiac itself – in the form of the Fixed, the Mutable, and the Cardinal Signs:

“The Fixed Signs – of which there are four fundamental forms that correspond to three interlocking compartments in the Black Zodiac – are the keepers of the earth. The Fixed Signs tend to come in threes, in three-fold guises.

Some cultures lump The Fixed Signs with the grand pantheon of nature spirits for specific places that they are inescapably destined to defend. The gorilla-looking Angongolood in Bicolandia folklore, protectors of marshes and riverbanks, have evolved with The Fixed Signs. So is the tree-dwelling whistling spirit that the Hiligaynon people know as the Palasekan.

Outside the city of Avenida and eighteen kilometres from Consolación Creek, where the bones of a previously unknown dinosaur species have recently been unearthed, the Fixed Signs occur as a couple and their child.”

Against an all-too-real backdrop of climate violence and unchecked urban expansion these archetypes warp the laws of time and space, acting as agents of nature’s revenge on unsuspecting contractors, as well as embodying more inexplicable cosmic forces. Ong-Muslim’s prose is measured and focussed, keeping things tense and controlled even during the most hallucinatory moments. Each vignette is like a prose poem on its own, and when read together the cumulative effect reveals glimpses of a world both atavistically familiar and disturbingly alien.

One would be wise to keep an eye on Ong-Muslim’s next expression of eclectic imagination.

‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’’s final piece is also the longest here: Damian Murphy’s inventive novella “A Night of Amethyst.” This atmospheric exploration of the occult machinations in an isolated manor is told in an ingenious form: as the play-through transcript of an obscure 1980s text-based adventure game. It’s not the first time that Murphy has used vintage gaming as a springboard for a story; indeed, in this volume’s predecessor ‘Drowning in Beauty: The Neo-Decadent Anthology’ his story “A Mansion of Sapphire” focussed on a young woman becoming ensnared by a ZX Spectrum game that detailed an esoteric quest. That story was told in the third person, while here we have a charming but ever-so-slightly acidic narrator describing the game for you in the second person. We begin:

“You stand in the lobby of an institution stained with scandal and ignominy. A symmetrical group of decorative lamps hang by thick strands from the ceiling. Their bulbs are shaped like rising flames and are arranged in tight concentric circles.

A slender front desk resides on the far end of the room, behind which stands a welldressed attendant. He wields the authority of the minor official whose expertise exceeds that of their superiors. His attention is absorbed in what appears to be an open registry.”

From here there is no point where one can tell what is next, as the exploration of this strange institution takes countless twists and turns. We steal from ornate eyescopes from desks, flee through luxurious hallways from irate attendants, and in a scene that brings to mind the intriguing visions of painter Remedios Varo, we provoke the ire of a gaggle of haughty poets by accidentally summoning a beam of arcane energy.

The second person narration gives everything a sense of playful urgency, with the gamemaster narrator becoming increasingly exasperated by your decisions and the troubles the cause:

“I suppose you ought to be congratulated. Once again, you’ve managed to cause some manner of catastrophe. If the house authorities weren’t already on your trail, they’re certain to pursue you now.“

For some the term “occult fiction” conjures visions of hellish visions and demonic rites, but “A Night of Amethyst” is far from horror. There are moments of tension for sure, but these are tempered by a sense of mischief and wonder. In lieu of cliché demons and left-hand path transgressions we discover arcane technologies and glimpse the workings of celestial bureaucracies.

In true occult fashion there are hints that a deeper something, a kind of esoteric message or hidden meaning, is hiding in the narrative. Whether or not this is really present in the text is left up to the reader, and no matter what the case “A Night of Amethyst” is as delightfully fun as any successful game, and ends ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ on a dizzying high note.

With ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ Justin Isis has curated a forward-thinking and most importantly entertaining collection of modern fiction. The vagaries of the 21st century are deftly described and explored by some of the most unique and uncompromising voices of the literary underground.

The torch of Neo-Decadence is illuminating the perennial decadent themes of obsession, hedonism, ennui, and Weltschmerz with new light, revealing for the still-young millennium both previously secret nooks and new hideous details. Those interested in spelunking the hidden chambers of desire are strongly recommended to order a copy of ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ today, as is anyone hungry for new voices and unique expressions in fiction.

I’ll let Damian Murphy have the last word here, with a pertinent passage of his “A Night of Amethyst” –

“You’ve scarcely begun to comprehend the complex mechanisms that lie behind the house.

Do play again.

Don’t be discouraged by the difficulty. Maybe next time you’ll make it a little bit further.

Every step is significant — even half-measures are of value.

Persistence, after all, is the only thing you really have. It’s the tiny lamp you carry with you through the endless night of being.”

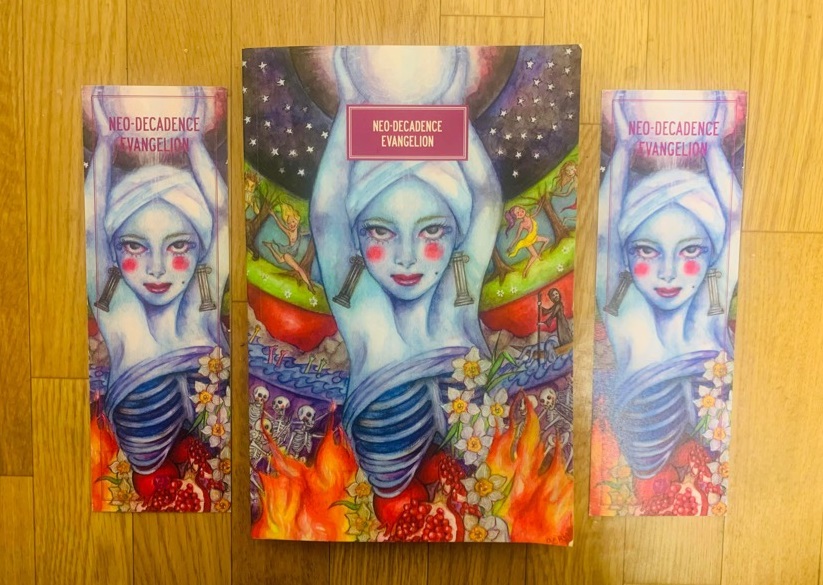

From left to right: Lettered Hardback, Paperback, and the Numbered Hardback.

Links

- Link to buy ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ – via Zagava Books

- ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ – GoodReads Entry

- ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ – Feature via Dennis Cooper’s Blog

- Link to review of ‘Neo-Decadence: 12 Manifestos’ (Snuggly Books, 2021) by Adam Symchuk – via The Aither

- Gea* – 2019 Interview via The Aither

- Justin Isis – 2021 Interview via The Aither

- Colby Smith – 2023 Interview via The Aither

- Zagava Books – Website

- Zagava Books – Instagram

- Zagava Books – Facebook

- Zagava Books – YouTube

All images supplied by Fergus and Justin or sourced online.

![Book Review – ‘Neo-Decadence Evangelion’ an Anthology Edited by Justin Isis; Featuring Brendan Connell, Golnoosh Nour, Arturo Calderon, Gaurav Monga, Audrey Szasz, Colby Smith, LC von Hessen, James Champagne, Kristine Ong Muslim, Damian Murphy, and Justin Himself [Zagava Books, 2023]](https://theaither.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/NGE-Cover.jpg)

![Comic Book Review – ‘Uno’ aka ‘One’ by David Marchetti [Hollow Press, 2021]](https://theaither.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/UNO-by-David-Marchetti-Cover-002-med-jpg-347x264.webp)

![Book Review – ‘Strong Songs of the Dead: The Pagan Rites of Sacred Harp’ by Th. Metzger [Underworld Amusements, 2024]](https://theaither.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/20241223_172612-sml-352x264.jpg)

![Zine Review – ‘Seraphim Sighted Cherubim Delighted’ by Fergus NM [Self Published, 2020]](https://theaither.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/SSCD-Zine-Cover-221x264.jpg)